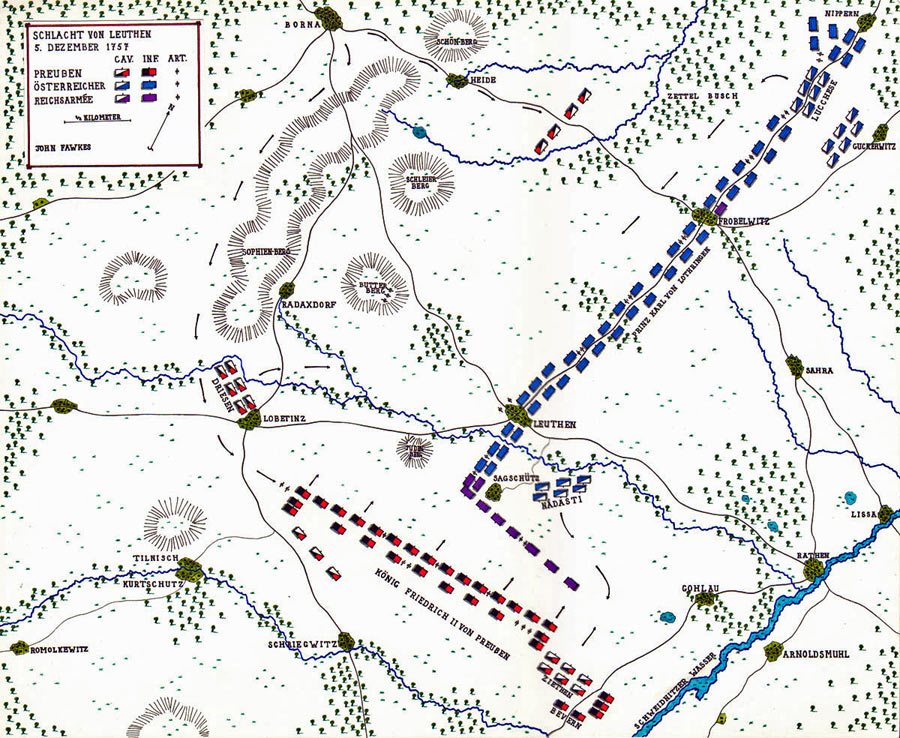

Frederick the Great’s overwhelming defeat of the Austrian Army, fought on 5th December 1757, in one of the major battles of the 18th Century

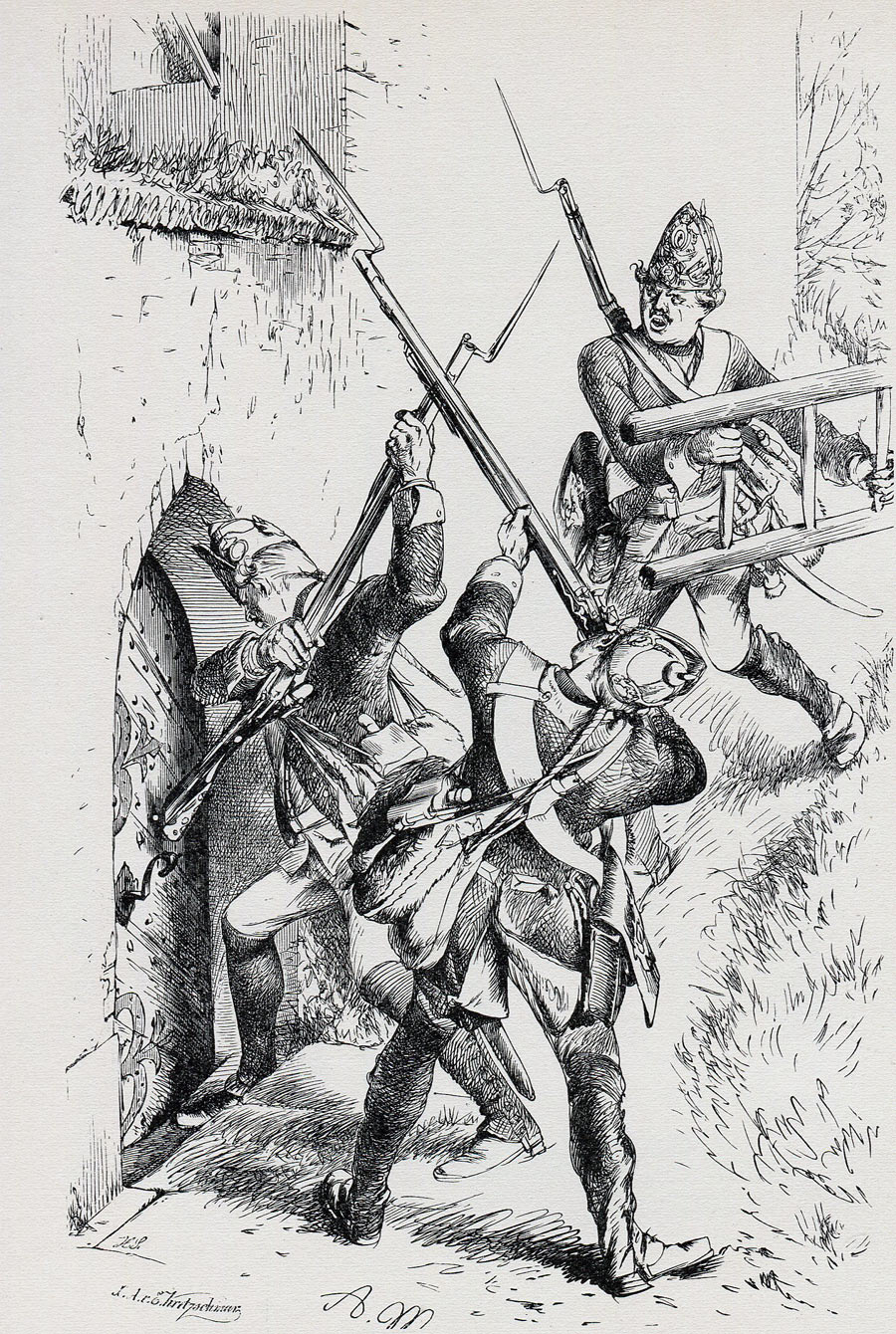

Prussian Grenadiers storming the church at the Battle of Leuthen on 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Rossbach

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Zorndorf

Battle: Leuthen

Date of the Battle of Leuthen: 5th December 1757.

Place of the Battle of Leuthen: In Central Silesia, on the road from Dresden to the Silesian capital of Breslau.

War: The Seven Years War.

Contestants at the Battle of Leuthen: Prussians against an Imperial Austrian Army comprising the various nationalities that made up the Hapsburg Empire (Austrians, Hungarians, Bohemians, Silesians, Croats, Italians and Moravians) with some Wϋrttemburg and Bavarian infantry regiments.

Generals at the Battle of Leuthen: King Frederick II of Prussia commanding the Prussian Army against Prince Charles of Lorraine, brother-in-law of the Empress Maria Theresa, commanding the Austrian Army.

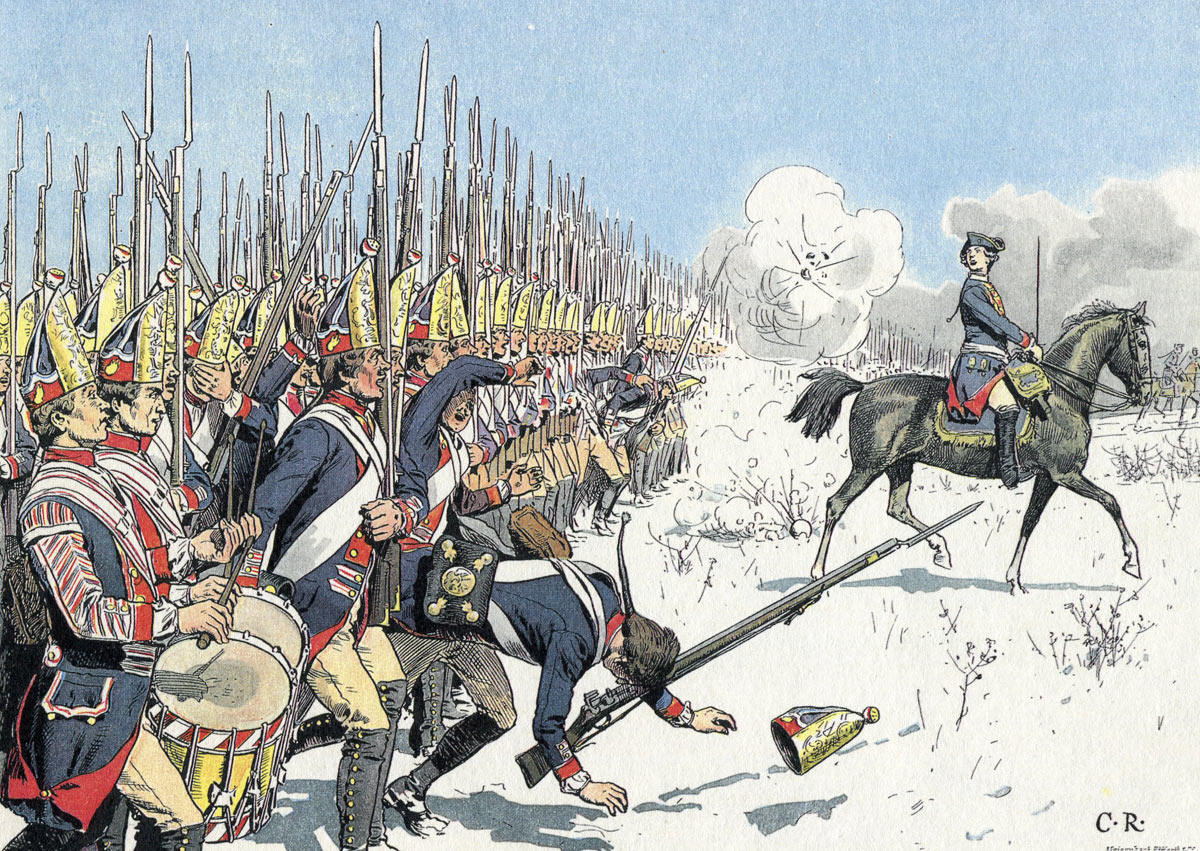

English Engraving of the Prussian attack at the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War

Size of the Armies at the Battle of Leuthen: Prussians: 21,000 infantry, 11,000 cavalry and 167 guns (33,000 in all). Austrians: 41,000 infantry, 22,000 cavalry and 210 guns (65,000 in all).

Winner of the Battle of Leuthen: A crushing victory for Frederick’s Prussian army.

Uniforms and equipment at the Battle of Leuthen: The Prussian infantry and artillery wore a dark blue coat turned back at the lapels, cuffs and skirts, with britches and black thigh length gaiters. Each soldier carried on a cross belt an ammunition pouch, bayonet and ‘hanger’ or small sword. Headgear for the line companies was the tricorne hat, with a flattened front corner, bound with white lace. Grenadiers wore the distinctive mitre cap with a brass plate at the front. Fusilier infantry regiments and artillery wore a smaller version of the grenadier cap.

The infantry carried a musket as the main weapon. This single shot firearm could be loaded and fired by a well trained soldier around 3 to 4 times a minute. As an early improvement Frederick introduced the iron ramrod and then the reversible ramrod (the soldier did not have to worry whether he had the ramrod the right way round) which increased the rate of fire of his infantry, the old wooden ramrod being liable to break in the stress of battle.

The Prussian infantry regiment was based on the cantonment with soldiers joining their local regiment. In peacetime soldiers were released for key agricultural times, sowing and harvesting. In the autumn, reviews were conducted of all regiments to check they were up to the required standard. Each year regiments were selected to undergo review at Potsdam under the eye of the King. Officers whose soldiers’ performance was considered by Frederick to be substandard were subject to a public tongue lashing and in extreme cases dismissal on the spot.

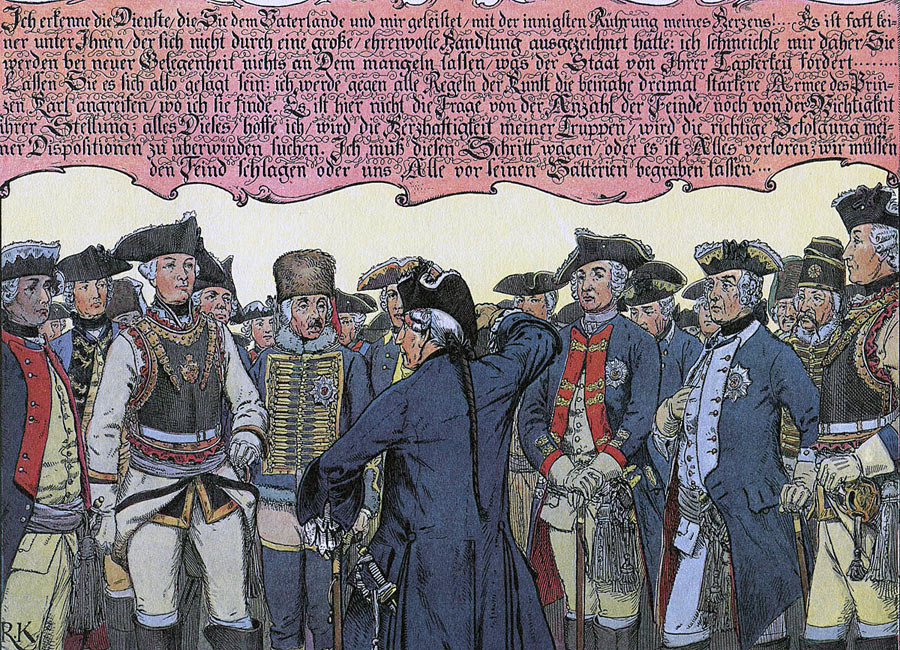

Frederick the Great and his staff at the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Hugo Ungewitter

The efficiency of the Prussian regiments at drill enabled them to move about the battlefield with a speed and manoeuvrability that no other European Army could equal. The Battle of Rossbach is a striking example of this facility.

During the peace between the sets of wars Frederick devised and practised his ‘oblique’ formation in attack. The technique was to deliver an assault on the flank of an enemy army. The Prussian infantry battalions would advance to the attack ‘in echelon’, or each battalion, after the leading battalion, setting off 50 paces after its predecessor. Leuthen was the only battle where Frederick was able to deliver a complete ‘oblique’ attack and did so with devastating success.

Another important contribution to the Prussian victory was the complete knowledge the Prussians and Frederick had of the ground on which the Battle of Leuthen was fought, having exercised over the area each year between 1746 and 1756.

Prussian Infantry Regiment Number 3 attacking at the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by G. Dorn

Heavy cavalry of the period comprised cuirassiers and dragoons. The Prussian cuirassiers wore a white coat, steel cuirass, white britches and thigh boots. Prussian Dragoons wore a light blue coat. The headgear was a tricorne hat. Weapons were a heavy cavalry sword and single shot flintlock carbine.

The light cavalry arm was provided by the Prussian Hussar regiments. The true hussars were Hungarians in the Austrian service. The hussars of other armies were given the same dress as the original hussars and required to perform a similar light cavalry role of reconnaissance and harassing the enemy’s outposts and supply columns.

Following the Battle of Mollwitz and in particular after the First Silesian War the Prussian Hussars were re-organised and re-trained to provide an efficient scouting and light cavalry service. Frederick found in Colonel von Zieten the ideal officer to implement the improvements in the hussar regiments. The Prussian Hussars wore the traditional hussar dress of tunic, britches, dolman (slung jacket), busby (fur hat) with bag, sabretache (leather wallet on straps hanging from the belt) and curved sword.

Unlike the original Hungarian Hussars of the time who were considered to be little more than indisciplined freebooters the Prussian Hussars were well able to take a position in the cavalry line and perform valuable service in battle, as at the Battle of Hohenfriedburg and on other occasions.

The Austrian infantry wore white coats with lapels, cuffs and skirts turned back showing the regimental lining colour. Headgear was the tricorne hat for line infantry and bearskin cap for grenadiers. The infantry weapons were musket, bayonet and hanger small sword. Heavy cavalry wore white coats and hats as for the infantry and were armed with a sword and carbine. Some dragoons wore a bearskin cap. The Austrian army contained a large number of irregular units notably the Pandours from the Balkans who wore their ethnic dress without uniformity. These light troops were referred to as ‘Grenzers’ or ‘Border Men’. Hungarian Hussars provided the light cavalry arm.

These Hussars, dressed as described for the Prussian Hussars, were considered to be little more than bandits but were highly effective in all the roles required of light cavalry.

Prussian Horse Artillery: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Frederick implemented significant improvements to the Prussian Army between the two Silesian wars. The eleven years of peace before the Seven Years War enabled Frederick to bring the various arms of the Prussian service to a further high pitch of efficiency. Each year the regiments were subjected to a training cycle that culminated in reviews at Potsdam under the King’s exacting eye. Autumn manoeuvres were held in Silesia, the area where much of the expected warfare would be conducted (see the benefit of these manoeuvres at the Battle of Leuthen).

The Prussian infantry was a tested and established asset and required little improvement. Most of the innovation was targeted at the cavalry, artillery and technical arms.

One unfortunate development from the Silesian Wars was that Frederick formed the view that his infantry could win their battles simply by the steadiness of their advance. The Seven Years War began with the Prussian infantry doctrine being to advance with muskets at the shoulder and not to pause to fire on the enemy. The Battle of Prague showed this doctrine to be badly misguided and it was abandoned after causing the Prussians substantial casualties.

The Prussian infantry was soon trained to advance making brief halts to fire and reload, enabling it to deliver successive volleys as it marched up to the opposing army, a technique used to devastating effect at the Battle of Rossbach.

During the course of the Seven Years War Frederick extensively re-organised the artillery. New equipment was introduced, the guns standardised and the artillery formations overhauled. Frederick introduced horse artillery that could move around the battlefield.

Frederick brought the Prussian cavalry to a level of effectiveness unrivalled by any other European Army of any period. The basic requirement was a high standard of horsemanship in every soldier. A trooper was required to ride his horse every day, an exacting obligation in peacetime. Contrast this with the practice of the British regiments of horse and dragoons of the time, in which as a measure of economy the horses had their shoes struck off and were put out to grass unridden for the whole of the summer (see Viscount Molesworth’s standing orders for his dragoon regiment).

Prussian fusiliers attacking: Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Alolph Menzel

Every year Frederick exercised the cavalry during the autumn manoeuvres. Frederick required the cuirassier and dragoon regiments to form line at the gallop and deliver a charge, with the troopers so close that they rode knee behind knee with the horses touching. Frederick developed the capability of the cavalry year by year. Finally he required his mounted regiments to be able to deliver three such charges one after the other at full gallop.

The effect of this exacting training was graphically illustrated by the performance of the Prussian cavalry force led by General von Seydlitz against the Russians at the Battle of Zorndorf on 25th August 1758. Seydlitz’s squadrons crossed the Zabern-Grun stream, climbed the steep far bank and moved through an area of scrub, before forming two lines of hundreds of troopers at the gallop, so close together that the horses were touching, and delivering a devastating charge at full gallop against unshaken Russian infantry, who were overwhelmed. Against cavalry of this quality it mattered little whether the infantry was in line or square.

This extraordinary ability contrasted with most other European cavalry regiments which would form for the charge at the halt and then attack in a loose formation which would be lost in the course of the charge, ending with the horses blown and all cohesion gone. If the infantry under attack seemed unduly aggressive, the attacking cavalry would be liable to swerve around them or pull up.

It was Frederick’s order that any Prussian cavalry commander receiving a charge at the halt would be tried by court-martial. Commanders had the discretion to attack if they considered that a favourable opportunity existed, without waiting for orders.

The Battle of Rossbach is another good example of the quality of the Prussian heavy cavalry and its ability to deliver battle winning charges through remaining under the tight control of its commander.

The Austrian army was also extensively re-organised and re-trained during the peace of 1746 to 1756. In particular Prince von Leichenstein completely re-organised, re-equipped and re-trained the Austrian artillery arm, using his personal fortune to pay for the changes, until it was considered to be more effective than the Prussian artillery at the beginning of the Seven Years War.

Parchwitz Address by Frederick the Great to his generals before the march to the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Richard Knötel

An efficient staff system was introduced into the Austrian army to relieve the burden on the generals.

Unfortunately for Austrian arms the establishment that surrounded Empress Maria Theresa insisted on maintaining Prince Charles of Lorraine as commander-in-chief when it was clear that he did not have the ability or technical expertise to command an army in the field, particularly against a commander like Frederick the Great and an army like the Prussian army. Professional Austrian commanders like Browne or Daun would have been unlikely to have given Frederick the opportunity that arose from Prince Charles’ advance out of the safety of the fieldworks around Breslau to the disaster of Leuthen.

Account of the Battle of Leuthen:

Following his decisive defeat of the French and the Reichsarmée at the Battle of Rossbach Frederick spent only two days in pursuit of the fleeing opposing troops before turning his army and marching for Silesia to deal with the invading Austrian army. As he hurried east he learnt that the Duke of Bevern had been defeated outside Breslau the capital of Silesia, his army escaping to the east bank of the Oder, while Breslau itself surrendered to the Austrians.

Frederick reached Parchwitz on the Oder on 28th November 1757 and waited for the various dispersed Prussian corps to join him. General Zieten brought in Bevern’s defeated troops (the Duke of Bevern himself had been captured).

Frederick the Great addresses his generals before the march to the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War

Frederick went out of his way to revive the spirits of his soldiers. He slept in the open air among their ranks. Extra rations were distributed. The foreign element in the Prussian army had largely deserted leaving only native Prussian soldiers, of whom the core were Pomeranians, Brandenburgers and Magdeburgers. Frederick revelled in their company. Ammunition was ample and the artillery was well equipped, Zieten having brought in a train of large field pieces from the armament at Glogau.

On 3rd December 1757 Frederick prepared to attack the Austrian army, which he expected to be positioned in the entrenchments outside Breslau they had captured from the Duke of Bevern.

King Frederick II of Prussia addresses his generals in the Parchwitz Address before the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War

He assembled his generals and regimental and battalion commanders and addressed them in what is known as the Parchwitz address. He was reported by Prince Ferdinand as saying: “The enemy hold the same entrenched camp of Breslau which my troops defended so honourably. I am marching to attack this position. I have no need to explain my conduct or why I am determined on this measure. I fully recognise the dangers attached to this enterprise, but in my present situation I must conquer or die. If we go under, all is lost. Bear in mind, gentlemen, that we shall be fighting for our glory, the preservation of our homes, and for our wives and children. Those who think as I do can rest assured that, if they are killed, I will look after their families. If anybody prefers to take his leave, he can have it now, but he will cease to have any claim on my benevolence.”

Frederick was proposing to attack an army twice the size of his own expected to be in carefully entrenched positions.

On 4th December 1757 the Prussian army marched out, heading south east towards Breslau on a route diverging from the Oder. Frederick rode with the advanced guard of the Puttkamer and Zieten Hussars.

As the Prussians approached the town of Neumarkt, townspeople informed them that the Austrian field bakeries and considerable stocks of food were in the town. At Frederick’s direction the Prussian hussars stormed the gates and captured the supplies.

Frederick spent the night in Neumarkt, where he received the momentous news that Prince Charles’s army had left the entrenchments outside Breslau and moved towards the Prussian army. A Lieutenant Hohenstock of the Prussian Hussars had observed the Austrians crossing the Schweidnitzer-Wasser and counted the cavalry standards of the powerful army before reporting back to his King.

Prussian Kürassier-Regiment Prinz

Schönaich No 9: picture by Adolph

Menzel as part of his series of pictures

‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen

in ihrer Uniformierung’

The stage was being set for Frederick’s perfect battle. In the years of peace between the Silesian Wars and the outbreak of the Seven Years War Frederick conducted the annual manoeuvres in this area of Silesia. There was no need for his hussars to bring back sketches of the geography. He and his army knew the countryside intimately.

What Frederick did not know was that the Austrian army comprised 65,000 troops and not the number he calculated at around 40,000.

At 5am on 5th December 1757 the Prussian army formed up in two infantry columns, flanked by the heavy cavalry, and marched to the south east across the wintry countryside. In front of the advance guard Frederick scouted the way ahead with the light troops and hussar regiments.

As the Prussians approached the town of Borna they attacked a force of Austrian hussars and took six hundred prisoners. The Prussian columns marched past the captured Austrians and into the town.

Prussian Dragoner-Regiment Württemberg No 12: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Frederick rode through Borna with Prince Moritz onto the Schön-Berg from where he surveyed the countryside to the east through his telescope. In front of him, from Nippern in the north to Leuthen in the south and beyond, stretched the Austrian line, some four miles in length. Colours waved over each infantry regiment and standards over the cavalry squadrons. Drums and trumpets sounded over the snow. Some two miles behind the Austrian line and parallel to it flowed the Schweidnitzer-Wasser.

Frederick issued his orders and the Prussians advanced to battle. The linked hills of Schleier-Berg and the Sophien-Berg concealed the columns as they turned south out of Borna, marched for some eight miles across the Austrian front to the village of Lobetinz, and then wheeled sharply to the east to bring them beyond the Austrian left flank. From there the Prussians would execute Frederick’s long planned and practised ‘attack in oblique order’ on the exposed Austrian flank. To distract Prince Charles from the true point of attack the hussars and troops of the Prussian advance guard moved out of Borna down the road towards Frobelwitz.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von

Meyerinck No 26, drummer: picture by

Adolph Menzel as part of his series

of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des

Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

The Austrians watched with amazement as the Prussian army appeared to advance to attack them. In contempt they named it the ‘Berlin Watch Parade’. Prince Charles and his senior generals were taken in by Frederick’s feint down the road from Borna. As Frederick intended, they became convinced that the main Prussian attack was to fall on the Austrian right flank. Prince Charles brought his army’s reserves to meet the anticipated threat between Frobelwitz and Nippern. The main weight of the Austrian line now lay on the extreme right, while the Prussian army was marching, unseen behind the low hills, to attack the distant Austrian left flank.

It was mid-morning by the time the main Prussian army began its march south out of Borna. At around noon the Prussians passed Lobetinz and wheeled to the south east. Lieutenant General von Zieten’s cavalry and Prince Carl of Bevern’s infantry, leading the army, stopped short of the Schweidnitzer-Wasser and turned to face the flank of the Austrian line to their left. The rest of the Prussian infantry halted and formed for the attack, facing north. The leading battalions on the right of the line were from the regiments of Meyerinck and Itzenplitz, commanded by Major General Wedel.

Prussian Infantry Regiment von Kannacher No 30: picture by Adolph Menzel as part of his series of pictures ‘Die Armee Friedrichs des Grossen in ihrer Uniformierung’

Frederick spent some time ensuring that the formations were correct. He addressed at length the two colour corporals of the leading battalion of Meyerinck’s regiment, pointing out where the attack was to be directed and instructing them to keep the pace steady so that the following battalions could keep up.

With some impatience Prince Moritz rode up to the king and reminded him that it was now 1pm and that there was little daylight left for the attack.

The Austrian left was commanded by the Hungarian Hussar General Nadasti. Nadasti watched with horror as the Prussian columns appeared behind Lobetinz and wheeled around his flank. He despatched orderly after orderly to Prince Charles at the other end of the Austrian line with messages that the Prussian attack was about to fall on the left flank. Prince Charles was unconvinced and slow to take action to remedy the situation. When no attack developed towards Frobelwitz he came to the conclusion that the Prussian army had seen the extent to which it was outnumbered and hurried away south in full retreat. In any case the Austrian line was so long that it took the best part of an hour to move a significant body of infantry from the right to the left. Nadasti was beyond assistance.

Prince Charles made a number of fatal errors. Unlike the Austrian generals Browne and Daun he consistently failed to appreciate the dangers of dealing with such an agile and aggressive foe as the Prussians led by Frederick. He had come out of a powerful entrenchment outside Breslau and taken up a long and exposed position without ensuring that his left flank was secured, as it might have been if he had caused it to rest on the Schweidnitzer-Wasser. It was a further mischance for Prince Charles that the regiments on his extreme left were not Austrian or Hungarian but regiments of Bavarians and Wϋrttemburgers. While competent soldiers the Wϋrttemburgers were mainly Protestants and their sympathies tended to be with the Prussians rather than against them.

Prussian attack at the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Carl Röhling

Soon after Prince Moritz’s reminder of the lateness of the hour Frederick launched the assault, the infantry regiments moving off from the right with each battalion fifty paces after its predecessor. The king sent a succession of orders to the leading troops to reduce the pace. He required his infantry to advance in perfect order. The Prussian attack struck the Wϋrttemburgers in their hastily prepared field fortifications. After a short hard struggle the Wϋrttemburg regiments dissolved. The Prussians pushed inexorably on towards Leuthen, supported by batteries of heavy guns that moved forward in support of the infantry.

General Zieten came up on the right of the Prussian infantry and was heavily engaged by General Nadasti’s cavalry. The cavalry combat ended with the Austrians driven back in confusion and 15 guns captured by the Prussians.

Once Prince Charles realised the true point of the Prussian attack he hurried troops from the right of the line into Leuthen. There was no opportunity to organise the Austrian regiments properly and the mass of infantry made an excellent target for the well served Prussian artillery, particularly a battery positioned on the Butter-Berg overlooking the town.

Prussian Grenadiers under Captain Möllendorf storm into the village of Leuthen during the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War

At around 3.30pm the Prussians launched a heavy attack on the Austrians in Leuthen. Guns were used to batter breaches in the stone walls of the town buildings. It took half an hour of the subsequent infantry assault to clear the Austrians out of the town.

As the Prussian infantry fought through Leuthen, a powerful force of Austrian cavalry led by General Lucchese rode down the front of the Austrian line from the right to counter-attack the Prussian assault. This move was met by General Driesen who led his Prussian cavalry from the area of Radaxdorf in an attack on Lucchese’s passing flank. The Bayreuth dragoons began the fight and were being worsted when the second line of cuirassiers charged the Austrian regiments. The Prussian hussar regiment of Puttkamer attacked in the rear of the Austrian cavalry and the Austrians were driven in confusion into the infantry attempting to hold Leuthen. The Austrian line began to collapse.

Prussian soldiers singing “Nun danket alle Gott” at the end of the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War

Frederick and Zieten gathered a force of cuirassiers and grenadiers and hurried to the town of Lissa to block the Austrian escape across the Schweidnitzer-Wasser. A spirited fight for the town took place while Frederick rode into the Schloss where he was entertained for the night by the owner, Baron Mudrach.

On the main battlefield the Austrian line dissolved in flight, leaving the Prussian infantry, cavalry and artillerymen the undisputed victors. In celebration of their good fortune the Prussian soldiers burst into the Lutheran hymn “Nun danket alle Gott” (Now thank we all our God).

Casualties at the Battle of Leuthen: Prussian losses were 6,382. Austrian losses were 22,000 including 11,000 prisoners.

Aftermath to the Battle of Leuthen:

The Prussians crossed the Schweidnitzer-Wasser the next day, 6th December 1757, and began to round up the Austrian baggage train. The Austrian army retreated towards Schweidnitz and the Bohemian border, while some thousands hurried into the city of Breslau.

Frederick the Great arriving at the Schloss von Lissa after the Battle of Leuthen 5th December 1757 in the Seven Years War: picture by Richard Knötel

The Austrians in Breslau surrendered the city on 21st December 1757, many thousands of soldiers going into captivity or being compelled to join the Prussian army. The main Austrian army returned to Bohemia, significantly smaller than the powerful force that had invaded Silesia earlier in the summer. Frederick resolved to turn to the siege of Schweidnitz in 1758 and the Prussian army went into winter quarters, where it fell victim to a savage epidemic that killed more soldiers than had been lost in all the fighting of the year.

Anecdotes from the Battle of Leuthen:

- Leuthen is considered Frederick’s most successful battle. Frederick fought 4 battles in 1757: Prague, Kolin, Rossbach and Leuthen, of which he won 3 and lost 1, Kolin.

- The victories of Prague, Rossbach and finally Leuthen established Frederick the Great as the hero of Protestant Europe.

- Following the Battle of Leuthen, Prince Charles was forced to resign as the Austrian commander in chief. General Nadasti was also dismissed, although it is hard to see how he could have been to blame for the disaster of Leuthen. It is said Nadasti’s dismissal was to appease the supporters of Prince Charles.

- The Prussian Guard’s attack on Leuthen was headed by Captain Möllendorf who led his battalion in the assault.

- In General Driesen’s attack on Lucchese’s cavalry the Bayreuth Dragoons led the charge. The regiment got into difficulties and the Prussian Cuirassiers of the second line left them to ‘stew’ for a bit before coming to their relief. The hero status of the Bayreuth Dragoons after their role in the Battle of Hohenfriedberg was not appreciated by all.

References for the Battle of Leuthen:

Frederick the Great by Thomas Carlile

Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Frederick the Great by Christopher Duffy

The Army of Maria Theresa by Christopher Duffy

The previous battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Rossbach

The next battle in the Seven Years War is the Battle of Zorndorf