The disastrous culmination in January 1842 to the British invasion of Afghanistan in the First Afghan War

Last stand of the 44th Regiment at the Battle of Gandamak on 13th January 1842 in the First Afghan War: picture by William Barnes Wollen

The previous battle in the First Afghan War is the Battle of Ghuznee

The next battle in the First Afghan War is the Siege of Jellalabad

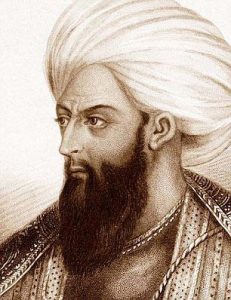

General William Elphinstone: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

Battle: Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak

War: First Afghan War

Date of the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak: January 1842.

Place of the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak: Central Afghanistan.

Combatants at the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak: British and Indians of the Bengal Army and the army of Shah Shuja against Afghans and Ghilzai tribesmen.

Commanders at the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak: General Elphinstone against the Ameers of Kabul, particularly Akbar Khan, and the Ghilzai tribal chiefs.

Size of the armies: 4,500 British and Indian troops against an indeterminate number of Ghilzai tribesmen, possibly as many as 30,000.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak:

The British infantry, wearing cut away red jackets, white trousers and shako hats, were armed with the old Brown Bess musket and bayonet. The Indian infantry were similarly armed and uniformed.

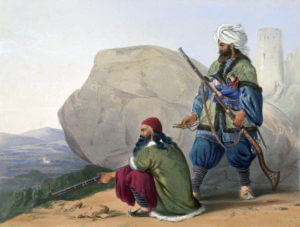

The Ghilzai tribesmen carried swords and jezail, long barrelled muskets.

Winner: The British and Indian force was wiped out other than a small number of prisoners and one survivor.

British Regiments at the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak:

44th Foot, later the Essex Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment.

Regiments of the Bengal Army:

2nd Bengal Light Cavalry

1st Bengal European Infantry

37th Bengal Native Infantry

48th Bengal Native Infantry

2nd Bengal Native Infantry

27th Bengal Native Infantry

Bengal Horse Artillery

The First Afghan War:

The British colonies in India in the early 19th Century were held by the Honourable East India Company, a powerful trading corporation based in London, answerable to its shareholders and to the British Parliament.

In the first half of the century France as the British bogeyman gave way to Russia, leading finally to the Crimean War in 1854. In 1839 the obsession in British India was that the Russians, extending the Tsar’s empire east into Asia, would invade India through Afghanistan.

This widely held obsession led Lord Auckland, the British governor general in India, to enter into the First Afghan War, one of Britain’s most ill-advised and disastrous wars.

Until the First Afghan War the Sirkar (the Indian colloquial name for the East India Company) had an overwhelming reputation for efficiency and good luck. The British were considered to be unconquerable and omnipotent. The Afghan War severely undermined this view. The retreat from Kabul in January 1842 and the annihilation of Elphinstone’s Kabul garrison dealt a mortal blow to British prestige in the East only rivalled by the fall of Singapore 100 years later.

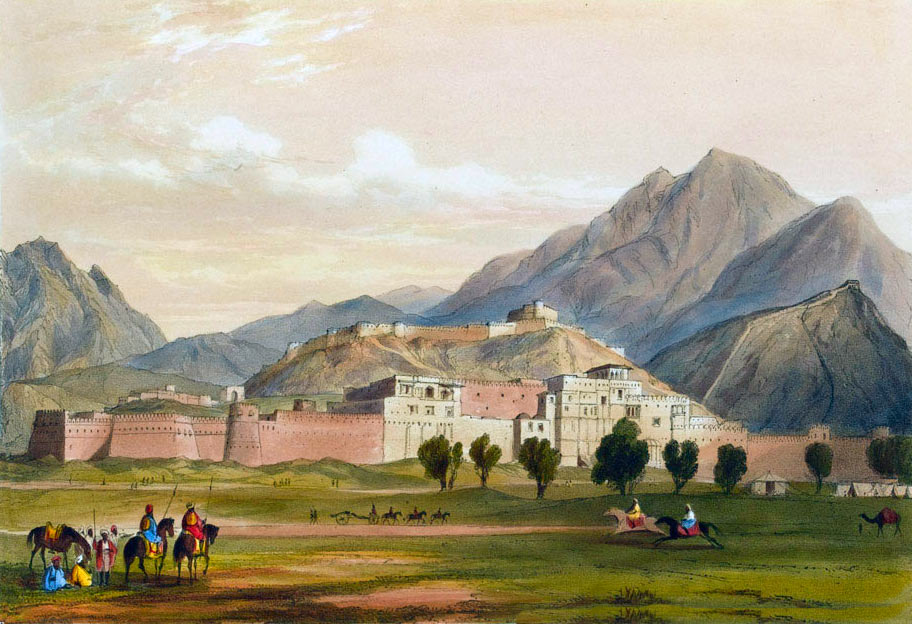

Balar Hissar Fortress at Kabul: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

The causes of the disaster are easily stated: the difficulties of campaigning in Afghanistan’s inhospitable mountainous terrain with its extremes of weather, the turbulent politics of the country and its armed and refractory population and finally the failure of the British authorities to appoint senior officers capable of conducting the campaign competently and decisively.

The substantially Hindu East India Company army crossed the Indus with trepidation, fearing to lose caste by leaving Hindustan and appalled by the country they were entering. The troops died of heat, disease and lack of supplies on the desolate route to Kandahar, subject, in the mountain passes, to constant attack by the Afghan tribes. Once in Kabul the army was reduced to a perilously small force and left in the command of incompetents. As Sita Ram in his memoirs complained: “If only the army had been commanded by the memsahibs all might have been well.”

The disaster of the First Afghan War was a substantial contributing factor to the outbreak of the Great Mutiny in the Bengal Army in 1857.

The successful defence of Jellalabad and the progress of the Army of Retribution in 1842 could do only a little in retrieving the loss of the East India Company’s reputation.

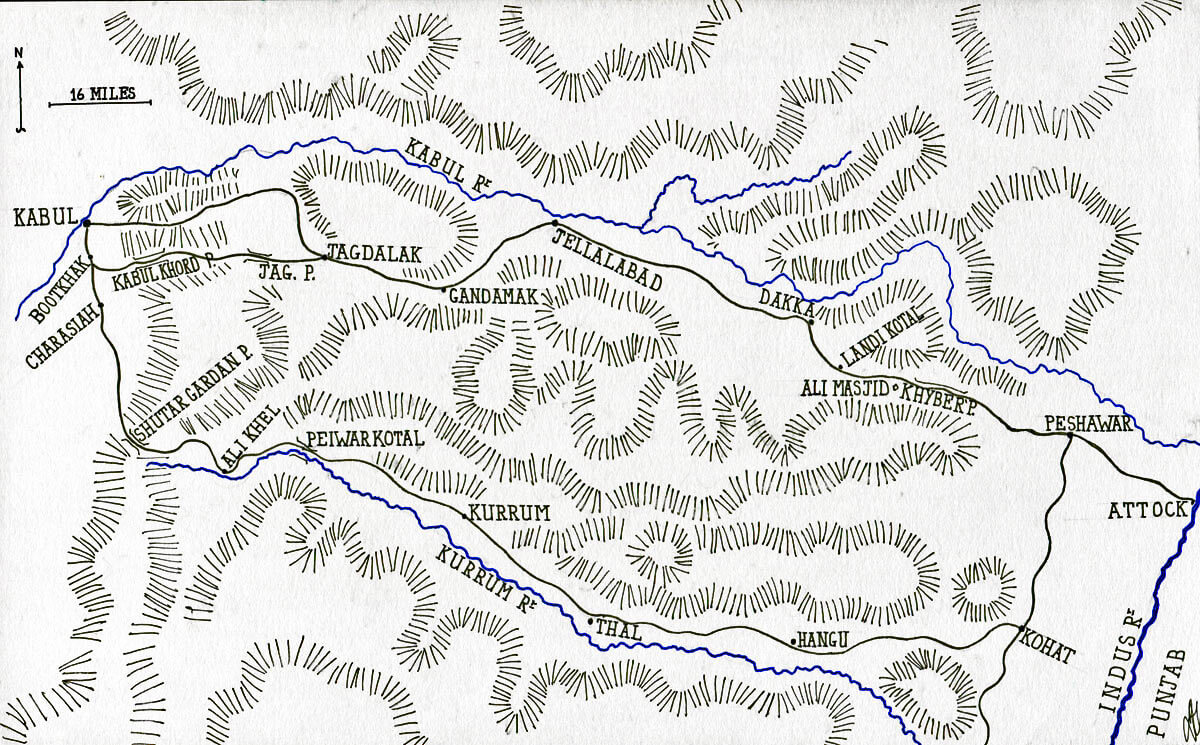

Map of the route from Kabul to Jellalabad and the border of India: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak:

Following the British capture of Kandahar and Ghuznee, Dost Mohammed, whose replacement on the throne in Kabul by Shah Shujah was the purpose of the British expedition into Afghanistan, despairing of the support of his army fled to the hills. On 7th August 1839 Shah Shujah and the British and Indian Army entered Kabul.

Dost Mohammed’s abandoned guns: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War: contemporary picture by James Atkinson

The British official controlling the expedition was Sir William Macnaghten, the Viceroy’s Envoy, acting with his staff of political officers.

At first all went well. British money and the powerful Anglo-Indian Army kept the Afghan tribes in controllable bounds, pacifying the Ameers with bribes and forays into the surrounding districts.

Surrender of Dost Mohammed to Sir William Macnaughten: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

In November 1840 during a raid into Kohistan, two squadrons of Bengal cavalry failed to follow their officers in a charge against a small force of Afghans led by Dost Mohammed himself. Soon afterwards, despairing of his life in the mountains, Dost Mohammed surrendered to Macnaghten and went into exile in India, escorted by a division of British and Indian troops no longer required in Afghanistan and accompanied by the commander in chief Sir Willoughby Cotton.

In December 1840, Shah Shujah and Macnaghten withdrew to Jellalabad for the ferocious Afghan winter, returning to Kabul in the spring of 1841.

On the assumption that the establishment of Shah Shujah as Ameer was complete, the British and Indian troops were required to move out of the Balla Hissar, a fortified palace of considerable strength outside Kabul, and build for themselves conventional cantonments. A further complete brigade of the force was withdrawn, leaving the remaining regiments to settle into garrison life as if in India, summoning families to join them, building a race course and disporting themselves under the increasingly menacing Afghan gaze.

There were plenty of signs of trouble. The Ghilzai tribes in the Khyber repeatedly attacked British supply columns from India. Tribal revolt made Northern Baluchistan virtually ungovernable. Shah Shujah’s writ did not run outside the main cities, particularly in the south-western areas around the Helmond River.

Sir William Cotton was replaced as commander in chief of the British and Indian forces by General Elphinstone, an elderly invalid now incapable of directing an army in the field, but with sufficient spirit to prevent any other officer from exercising proper command in his place.

The fate of the British and Indian forces in Afghanistan in the winter of 1840 to 1841 provides a striking illustration of the collapse of morale and military efficiency, where the officers in command are indecisive and lacking in initiative and self-confidence. The only senior officer left in Afghanistan with any ability was Brigadier Nott, the garrison commander at Kandahar.

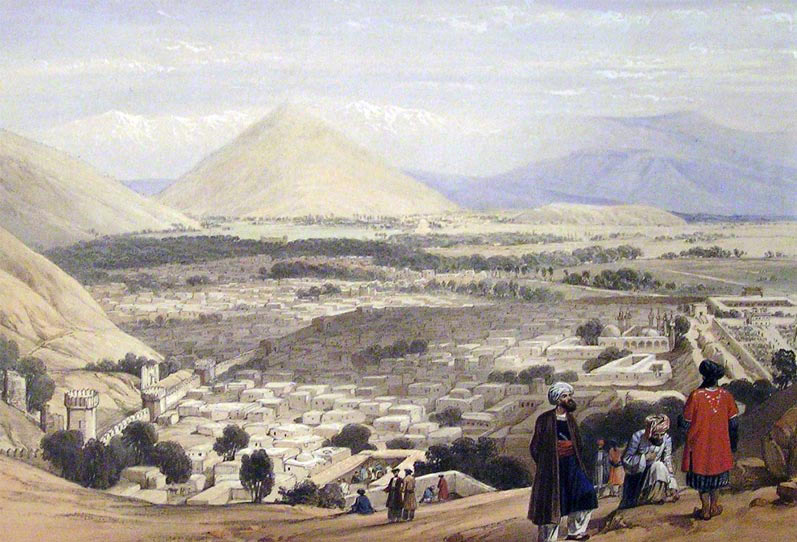

Balar Hissar Fortress and the city of Kabul: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

Crisis struck in October 1841. In that month, Brigadier Sale took his brigade out of Kabul as part of the force reductions and began the march through the mountain passes to Peshawar and India. During the journey, his column was subjected to repeated attack by Ghilzai tribesmen and the armed retainers of the Kabul Ameers. Sale’s brigade, which included the 13th Foot, fought through to Gandamak, where a message was received summoning the force back to Kabul, Sale did not comply with the order and continued to Jellalabad.

Murder of Sir Alexander Burnes in Kabul: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

In Kabul, serious trouble had broken out. On 2nd November 1841, an Afghan mob stormed the house of Sir Alexander Burnes, one of the senior British political officers, and murdered him and several of his staff. It is the authoritative assessment that if the British had reacted with vigour and severity the Kabul rising could have been controlled. But such a reaction was beyond Elphinstone’s abilities. All he could do was refuse to give his deputy, Brigadier Shelton, the discretion to take such measures.

Until the end of the year the situation of the Kabul force deteriorated, as the Afghans harried them and deprived them of supplies and pressed them more closely.

On 23rd December 1841 Macnaghten was lured to a meeting with several Afghan Ameers and murdered. While the Kabulis awaited a swift retribution the British and Indian regiments cowered fearful in their cantonments.

The Murder of Sir William Macnaughten: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

Attempts to clear the high ground that enabled the Afghans to dominate the cantonments failed miserably, because the troops were too cowed to be capable of aggressive action.

Afghan tribesmen: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War: contemporary picture by James Atkinson

The beginning of the end came on 6th January 1842, when the British and Indian garrison, 4,500 soldiers, including 690 Europeans, and 12,000 wives, children and civilian servants, following a purported agreement with the Ameers guaranteeing safe conduct to India, marched out of the cantonments and began the terrible journey to the Khyber Pass and on to India.

As part of the agreement with the Ameers, all the guns were to be left to the Afghans except for one horse artillery battery and three mountain guns, and a number of British officers and their families were required to surrender as hostages, taking them from the nightmare slaughter of the march into relative security.

In spite of the binding undertaking to protect the retreating army, the column was attacked from the moment it left the Kabul cantonments.

The army managed to march six miles on the first day. The night was spent without tents or cover, many troops and camp followers dying of cold.

The next day, 7th January 1842, the march continued. Brigadier Shelton, after his ineffectiveness as Elphinstone’s deputy, showed his worth by leading the counter attacks of the rear-guard to cover the main body.

Grove and Valley of Jugduluk: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

At Bootkhak, the Kabul Ameer, Akbar Khan, arrived, claiming he had been deputed to ensure the army completed its journey without further harassment. He insisted that the column halt and camp, extorting a large sum of money and insisting that further officers be given up as hostages. One of the conditions negotiated was that the British abandon Kandahar and Jellalabad. Akbar Khan required the hostages to ensure Brigadier Sale left Jellalabad and withdrew to India.

The next day found the force so debilitated by the freezing night that few of the soldiers were fit for duty. The column struggled into the narrow five-mile-long Khoord Cabul pass, to be fired on for its whole length by the tribesmen posted on the heights on each side. The rear-guard was formed of men from the 44th Regiment, who fought to keep the tribesmen at bay. 3,000 casualties were left in the gorge.

Afghan tribesmen attacking the Anglo-Indian army in the Koord Kabul pass: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

On 9th January 1842, Akbar Khan required further hostages, being the remaining married officers with their families. For the next two days, the column pushed on through the passes, fighting off the incessant attacks of the tribesmen.

On the evening of 11th January 1842, Akbar Khan compelled General Elphinstone and Brigadier Shelton to surrender as hostages, leaving the command to Brigadier Anquetil. The troops reached the Jugdulluk crest to find the road blocked by a thorn abatis manned by Ghilzai tribesmen. A desperate attack was mounted, the horse artillery driving their remaining guns at the abatis, but few managed to pass this fatal obstruction.

The final stand took place at Gandamak on the morning of 13th January 1842 in the snow. 20 officers and 45 European soldiers, mostly from the 44th Foot, found themselves surrounded on a hillock. The Afghans attempted to persuade the soldiers that they intended them no harm. Then the sniping began, followed a series of rushes. Captain Souter wrapped the colours of the regiment around his body and was dragged into captivity with two or three soldiers. The remainder were shot or cut down. Only six mounted officers escaped. Of these, five were murdered along the road.

Afghan tribesmen attacking the Anglo-Indian army in the Koord Kabul pass: Battle of Kabul and Retreat to Gandamak 1842 during the First Afghan War

On the afternoon of 13th January 1842, the British troops in Jellalabad, watching for their comrades of the Kabul garrison, saw a single figure ride up to the town walls. It was Dr Brydon, the sole survivor of the column.

Casualties at the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak:

The entire force of 690 British soldiers, 2,840 Indian soldiers and 12,000 followers were killed, or, in a few cases, taken prisoner. The 44th Foot lost 22 officers and 645 soldiers, mostly killed. Afghan casualties, largely Ghilzai tribesmen, are unknown.

Follow-up to the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak:

The massacre of this substantial British and Indian force caused a profound shock throughout the British Empire. Lord Auckland, the Viceroy of India, is said to have suffered a stroke on hearing the news. Brigadier Sale and his troops in Jellalabad for a time contemplated retreating to India, but more resolute councils prevailed, particularly from Captains Broadfoot and Havelock, and the garrison hung on to act as the springboard for the entry of the ‘Army of Retribution’ into Afghanistan the next year.

‘Remnants of an Army’: Dr Brydon, last survivor of the Anglo-Indian Army in the retreat from Kabul and the Battle of Gandamak in January 1842 during the First Afghan War: picture by Lady Butler

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak:

- The First Afghan War provided the clear lesson to the British authorities that, while it may be relatively straightforward to invade Afghanistan, it is wholly impracticable to occupy the country or attempt to impose a government not welcomed by the inhabitants. The only result will be failure and great expense in treasure and lives.

- The British Army learnt a number of lessons from this sorry episode. One was that the political officers must not be permitted to predominate over military judgments.

- The War provides a fascinating illustration of how the character and determination of its leaders can be decisive in determining the morale and success of a military expedition.

- It is extraordinary that officers, particularly senior officers like Elphinstone and Shelton, felt able to surrender themselves as hostages, thereby ensuring their survival, while their soldiers struggled on, to be massacred by the Afghans.

References for the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak:

Afghanistan From Darius to Amanullah by Lieutenant General Sir George McMunn.

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes.

History of the British Army by Fortescue

The previous battle in the First Afghan War is the Battle of Ghuznee

The next battle in the First Afghan War is the Siege of Jellalabad