The British capture of the Afghan city of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839: a successful beginning to a disastrous war

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Waterloo

The next battle in the First Afghan War is the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak

Battle: Ghuznee

War: First Afghan War

Date of the Battle of Ghuznee: 23rd July 1839

Place of the Battle of Ghuznee: Central Afghanistan

Combatants at the Battle of Ghuznee: British and Indian troops of the Bengal and Bombay Armies, allied to the army of Shah Shuja, against the Afghan army of Dost Mohammed.

Commanders at the Battle of Ghuznee: General Sir John Keane, Commander in Chief of the Bombay Army against Hyder Khan, a son of the Amir Dost Mohammed.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Ghuznee: 9,500 British and Indian troops of the Bengal Army, 5,000 troops of the Bombay Army and 6,000 men led by Shah Shujah, against the Afghan garrison of 3,500 men.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Ghuznee:

The British infantry, wearing cut away red coats, white trousers and shako hats, were armed with the old Brown Bess musket and bayonet. The Indian infantry were similarly armed and uniformed.

The 4th Hussars wore the standard hussar uniform of pelisse, dolman and shako rather than a busby, and were armed with swords and carbines.

The 16th Lancers wore scarlet tunics and the Polish tzapka hat and carried carbines, swords and lances.

The Afghan soldiers were dressed as they saw fit, and carried an assortment of weapons, including muskets and swords.

The Ghilzai tribesmen carried swords and jezails, long barrelled muskets.

Camp at Dadur at the entrance to the Bolan Pass: Battle of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839 in the First Afghan War

Winner: The British and Indian Army.

British and Indian Regiments at the Battle of Ghuznee:

British:

4th Hussars, now the Queen’s Royal Hussars. *

16th Lancers now the Queen’s Royal Lancers. *

2nd Queen’s Foot now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment. *

13th Foot later the Light Infantry and now the Rifles. *

17th Foot now the Royal Anglian Regiment. *

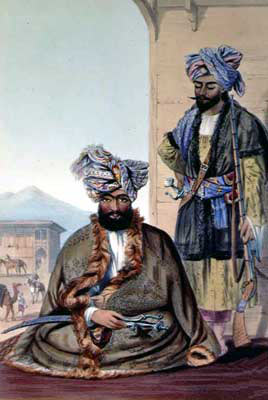

Lord George Paget HM 4th Light Dragoons (Hussars): Battle of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839 in the First Afghan War

Indian:

2nd Bengal Light Cavalry

3rd Bengal Light Cavalry

3rd Skinner’s Horse *

31st Lancers *

34th Poona Horse *

3rd Sappers and Miners *

Shah Shujah’s Regiment

1st Bengal Fusiliers (European Regiment) later the Munster Fusiliers. *

2nd Bengal Native Infantry

16th Bengal Native Infantry

19th Bombay Infantry later the 119th Multan Regiment. *

27th Bengal Native Infantry

31st Bengal Native Infantry

42nd Bengal Native Infantry

43rd Bengal Native Infantry

48th Bengal Native Infantry

* These regiments have Ghuznee as a battle honour. The Bengal native regiments were all swept away in the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

The First Afghan War:

The British colonies in India in the early 19th Century were ruled by the Honourable East India Company, a powerful trading corporation based in London, answerable to its shareholders and to the British Parliament.

In the first half of the 19th Century, France as the British bogeyman gave way to Russia, leading finally to the Crimean War in 1854. In 1839 the obsession in British India was that the Russians, extending the Tsar’s empire east into Asia, would invade India through Afghanistan.

This widely held obsession led Lord Auckland, the British governor general in India, to enter the First Afghan War, one of Britain’s most ill-advised and disastrous wars.

Until the First Afghan War, the Sirkar (the Indian colloquial name for the East India Company) had an overwhelming reputation for efficiency and good luck. The British were considered to be unconquerable and omnipotent. The Afghan War severely undermined this view. The retreat from Kabul in January 1842 and the annihilation of Elphinstone’s Kabul garrison dealt a mortal blow to British prestige in the East only rivalled by the fall of Singapore 100 years later.

The causes of the disaster are easily stated: the difficulties of campaigning in Afghanistan’s inhospitable mountainous terrain, with its extremes of weather, the turbulent politics of the country and its armed and refractory population, and, finally, the failure of the British authorities to appoint senior officers capable of conducting the campaign competently and decisively.

The substantially Hindu East India Company army crossed the Indus with trepidation, fearing to lose caste by leaving Hindustan, and appalled by the country they were entering. The troops died of heat, disease and lack of supplies on the desolate route to Kandahar, subject, in the mountain passes, to repeated attack by the Afghan tribes. Once in Kabul, the army was reduced to a perilously small force and left in the command of incompetents. As the Bengal Army soldier, Sita Ram, in his memoirs complained: ‘If only the army had been commanded by the memsahibs, all might have been well.’

The disaster of the First Afghan War was a substantial contributing factor to the outbreak of the Great Mutiny in the Bengal Army in 1857, and, more immediately, led to wars in Sind, Gwalior and against the Sikhs in the Punjab.

The successful defence of Jellalabad and the progress of the Army of Retribution in 1842 could do only a little to retrieve the East India Company’s lost reputation.

Account of the Battle of Ghuznee:

By the 1830s, the British Indian Empire stretched to the border of the Sikh Kingdom of the Punjab, in the North West. The British increasingly considered their responsibilities extended over the whole of the Indian sub-continent, even though many of the Indian states retained their independence. There was little to fear from these kingdoms. What did cause alarm was the threat from the Russian Empire.

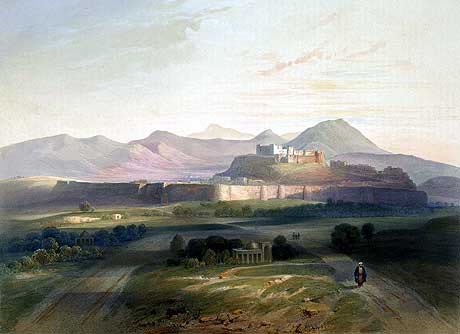

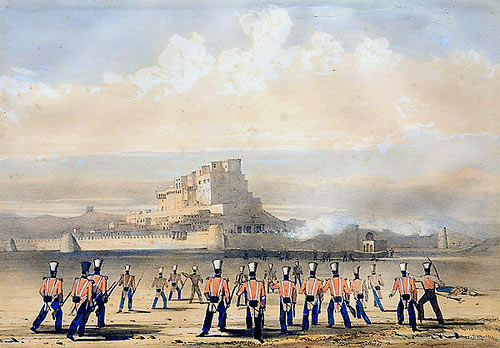

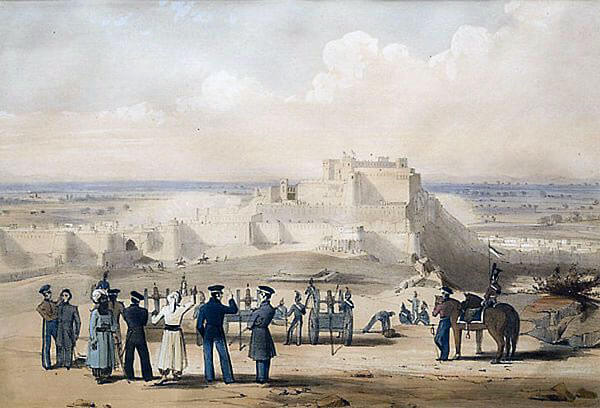

Town of Ghuznee: Battle of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839 in the First Afghan War: picture by Lieutenant Thomas Wingate

Tsarist expansion, down the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, south towards Persia and Western Afghanistan, and to the north of the Himalayas, created a concern for the British that became an obsession; the perceived British/Russian rivalry known during the 19th Century as ‘The Great Game’.

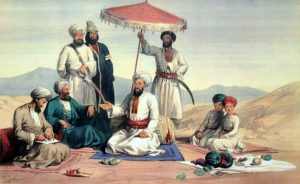

In 1838, a joint Persian/Russian force laid siege to Herat, the important north-western Afghan city. The British Viceroy in India, Lord Auckland, and his advisers planned an invasion of Afghanistan to combat the siege of Herat, and to place an Ameer favourable to Britain on the throne in Kabul, the Afghan capital, in place of the existing incumbent, Dost Mohammed. The candidate to be made Ameer was Shah Shujah, then languishing in the Sikh capital Lahore on an East India Company pension.

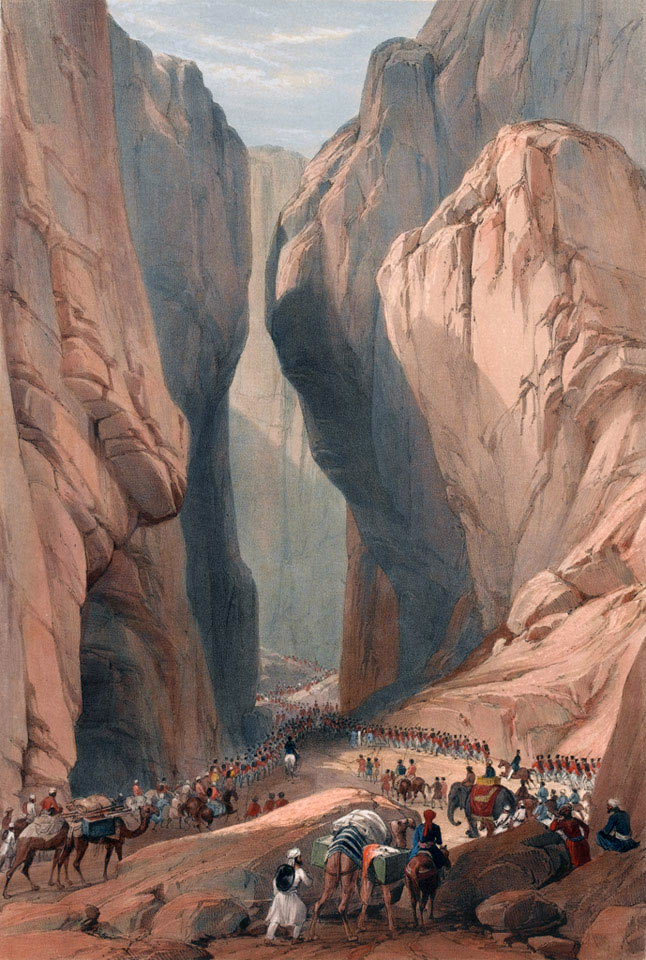

Army of the Indus marching into Afghanistan: Battle of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839 in the First Afghan War: picture by Lieutenant Rattray

A force of two divisions from the Bengal Army, under the commander in chief, Sir Harry Fane, assembled in Ferozepore on the border of the Punjab, under the name ‘the Army of the Indus’.

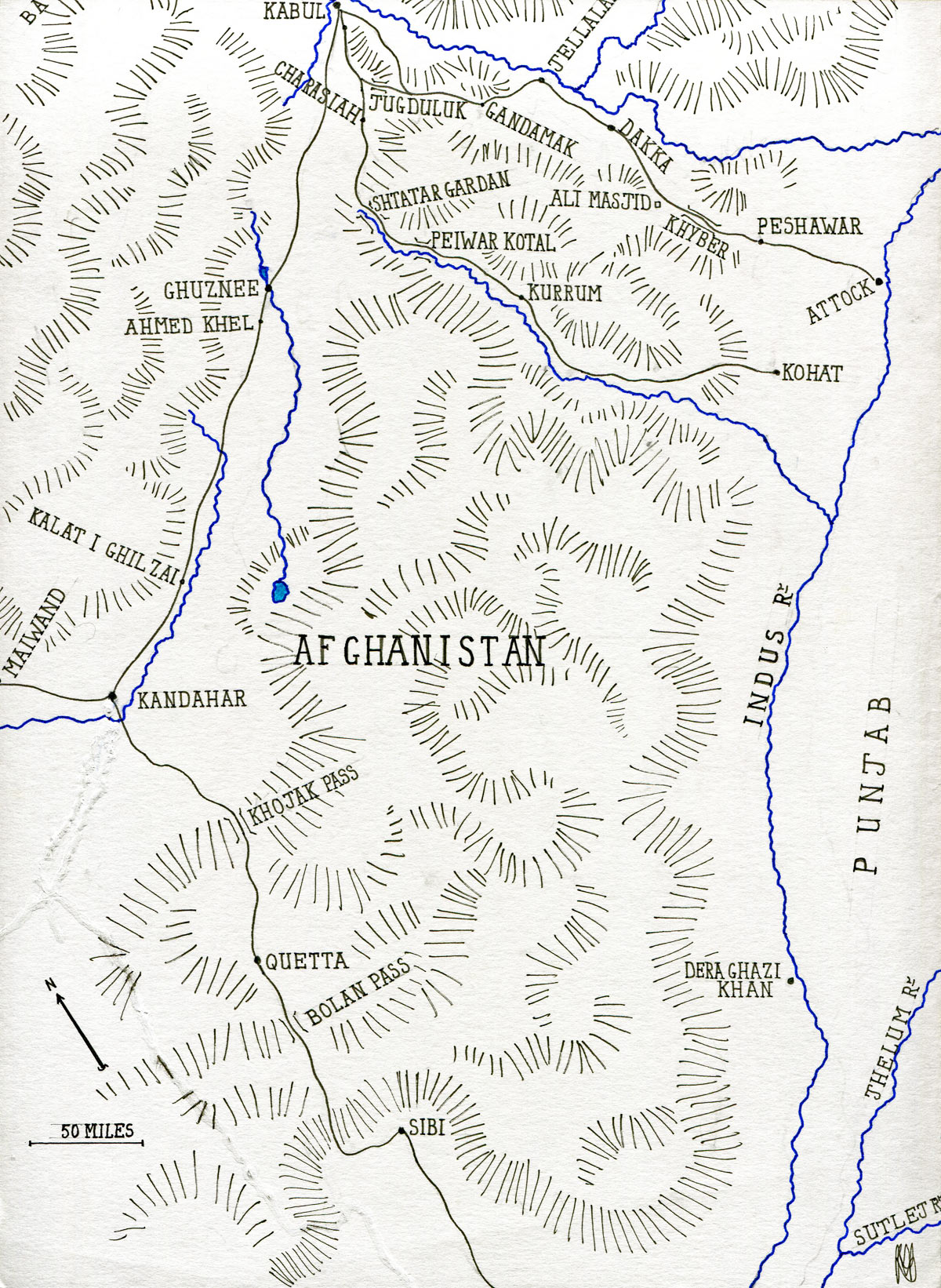

The quickest route to Kabul was to march across the Punjab and enter Afghanistan by way of Peshawar and the Khyber Pass, but Ranjit Singh, the Sikh ruler of the Punjab, would never consent to such a large British force crossing the Punjab. The invasion route had to be through the southern passes, with the approach to Kabul via Kandahar and Ghuznee; a journey three times the distance of the direct route.

A second force of a single division from the Bombay Army, under its commander in chief, Sir John Keane, would join the Bengal force, landing by sea at the mouth of the Indus.

Before the march could begin, news reached India that the Persians and Russians had abandoned the siege of Herat. The view of many British officials was that the reason for the invasion of Afghanistan had gone. Lord Auckland resolved to continue with his plan, although the size of the force was scaled down, with the second Bengal division remaining as a reserve at Ferozepore.

The nominated commander in chief of the army, Sir Harry Fane, refused to take further part in the venture, leaving the command to Sir John Keane.

The Army of the Indus began the campaign in December 1838, marching down the left bank of the Indus, to cross at Roree for the journey to Quetta, where the rendezvous with the force from the Bombay Army would take place. The Indus was crossed by a long bridge of boats, built by the Bengal Army Sappers and Miners. A diversion to quell the Ameers of Scinde briefly delayed the march.

Army of the Indus passing through the Bolan Pass: Battle of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839 in the First Afghan War

The Bombay and Bengal forces met at Quetta and prepared for the invasion of Afghanistan. Supplies were low and the troops near to starvation. The Army hurried, as best it could, up the Bolan and Kojuk passes and marched the one hundred and forty-seven miles to Kandahar, arriving on 4th May 1839. The local leaders showed their opinion of their new Ameer, arriving with his British sponsors, by escaping to the west.

Sir John Keane continued his advance towards Kabul on 27th June 1839, after a foray to Girishk on the Helmond River, in pursuit of the fleeing Khans of Kandahar, and the storming of the fortress of Khelat. A severe shortage of draft horses forced Keane to leave his siege train in Kandahar.

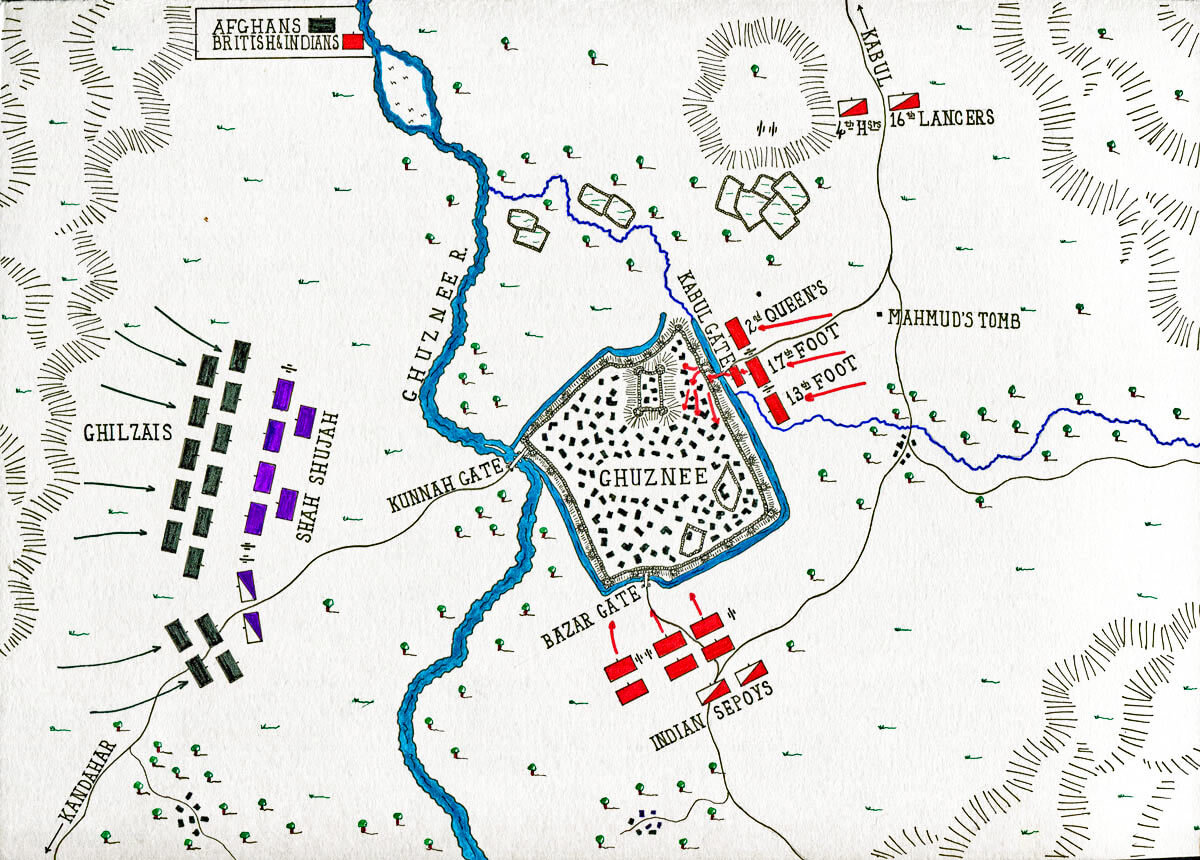

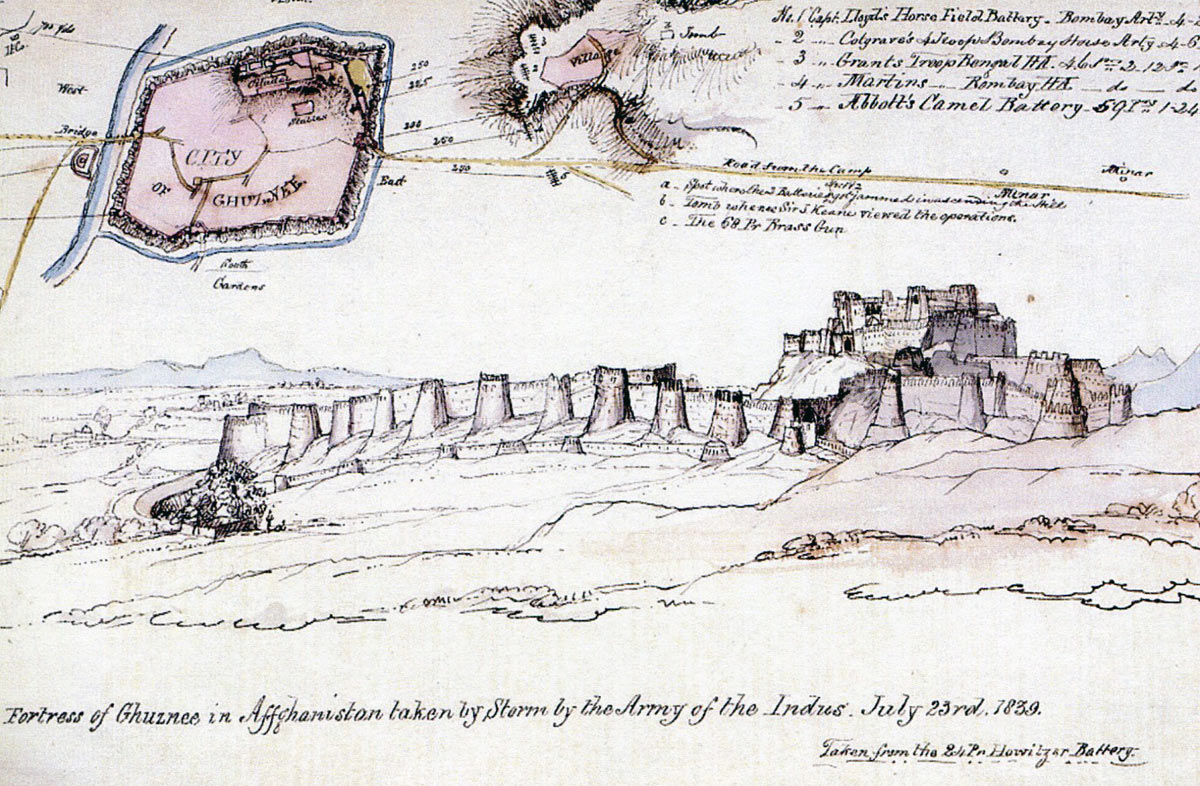

On 21st July 1839, the army arrived before Ghuznee, an important town on the road to Kabul. Reconnaissance showed Ghuznee to be occupied in force and strongly fortified, with a seventy foot wall and a flooded moat. The lack of a siege train was now severely felt. The town had to be taken, before the final advance to Kabul, and the only way was by storm, promising heavy losses.

The Army’s chief engineer, Colonel Thompson, reconnoitred the town and interviewed captured Afghans. This intelligence revealed that the garrison had sealed all the gates by piling stones and debris behind them; that is except the Kabul Gate to the north. Thompson observed this gate and saw an Afghan courier admitted to the town. The gate appeared to be clear and inadequately defended. This was the only possible point of assault. The Army marched around Ghuznee, and camped on the north side to prepare for the attack.

On 22nd July 1839, thousands of Ghilzai tribesmen attacked Shah Shujah’s contingent, and had to be repelled. The preparations for storming the Kabul Gate were then made. Artillery was positioned to cover the approach, and the light companies of the three British regiments (HM 2nd, 13th and 17th Foot) and the one Bengal European regiment were formed into a storming party, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Dennie of HM 13th Foot. The rest of the three British regiments formed the main attacking column commanded by Brigadier Sale. High winds prevented the garrison from realising they were about to be attacked.

At 3am on 23rd July 1839 a party of engineers commanded by Captain Peat of the Bombay Sappers and Miners moved towards the gate. Lieutenant Durand commanded the explosion party.

The engineers were one hundred and fifty yards from the gate, when they were challenged and fire given from the town wall, blue flares being thrown down from the battlements to illuminate the scene. The British artillery opened a bombardment of the walls, and musket and gun fire erupted around the town.

Peat’s party rushed forward to the wall, and Durand’s men placed powder bags against the gate and unrolled a length of quick match which they lit. The explosion blew in the gate.

The signal to attack was to be given by Peat’s bugler, but he was killed. Durand hurried back and brought forward the storming party. Dennie’s four light companies rushed through the shattered gate and met the Afghan defenders in a savage hand to hand fight in the semi-dark of the gate tunnel.

An Afghan counterattack cut Dennie’s party off from the supporting column. Sale was severely wounded by an Afghan swordsman as his men joined the attack. Finally, the British column cut its way through the gate into the streets beyond. The citadel was found to be undefended and the town was in British hands by dawn.

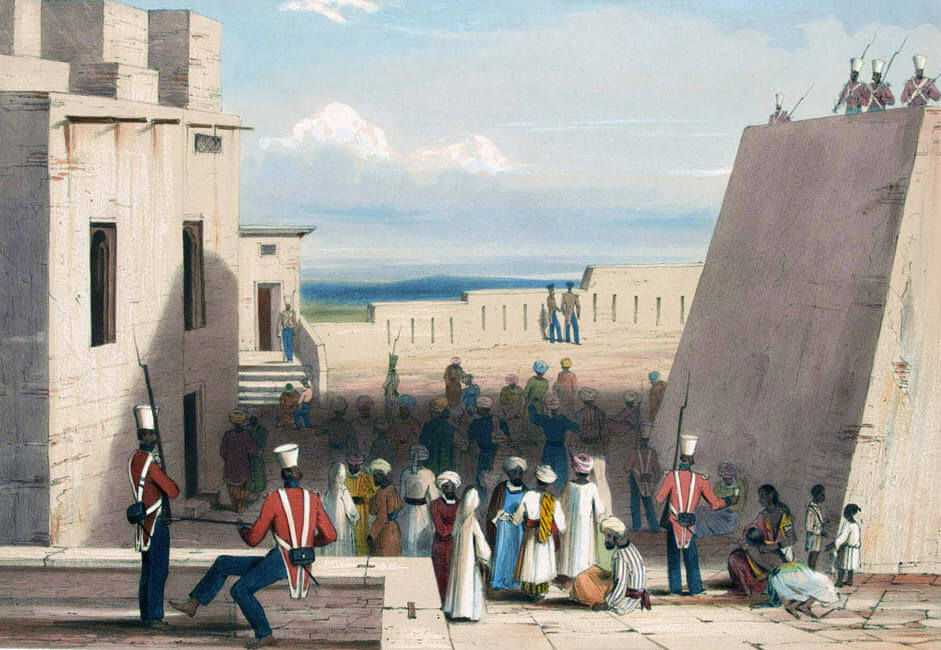

Afghan prisoners guarded by 19th Bengal Native Infantry after the Battle of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839 in the First Afghan War

Casualties at the Battle of Ghuznee: British casualties were 200 killed and wounded. The Afghans lost 500 killed and 1,600 prisoners. The number of wounded is not known.

Follow-up to the Battle of Ghuznee:

Keane left a garrison in Ghuznee, and the Army marched on towards Kabul on 30th July 1839. When Dost Mohammed heard of the fall of Ghuznee, he sent to the British asking what terms he was offered. The answer was ‘honourable asylum in India’. This was not acceptable, but his army would not fight. Dost Mohammed fled his capital, leaving it to the invading British and their puppet ruler, Shah Shujah.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Ghuznee:

- General McMunn in his book ‘Afghanistan from Darius to Amanullah’ states that the Army of the Indus was taken by surprise when it moved from India proper into the area north-west of the Indus, where the usual network of Indian merchants and suppliers did not reach, with the consequence that there were no supplies to be bought. This is the same problem that British generals encountered in America (see Braddock on the Monongahela).

- The medal to mark the capture of Ghuznee was issued on the orders of Shah Shujah, once he was established as the Ameer of Afghanistan, and issued to the soldiers of General Keane’s army.

References for the Battle of Ghuznee:

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes

Afghanistan from Darius to Amanullah by General McMunn

History of the British Army by Fortescue.

Plan of Ghuznee by Lieutenant Thomas Gaisford Bombay Artillery: Battle of Ghuznee on 23rd July 1839 in the First Afghan War

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Waterloo

The next battle in the First Afghan War is the Battle of Kabul and the Retreat to Gandamak