The revenge taken by the Anglo-Indian ‘Army of Retribution’ against the Afghans between August and October 1842 for the massacres at Kabul and Gandamak

The previous battle in the First Afghan War is the Siege of Jellalabad

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Moodkee

Battle: Kabul 1842

War: First Afghan War

Date of the Battle of Kabul 1842: August to October 1842.

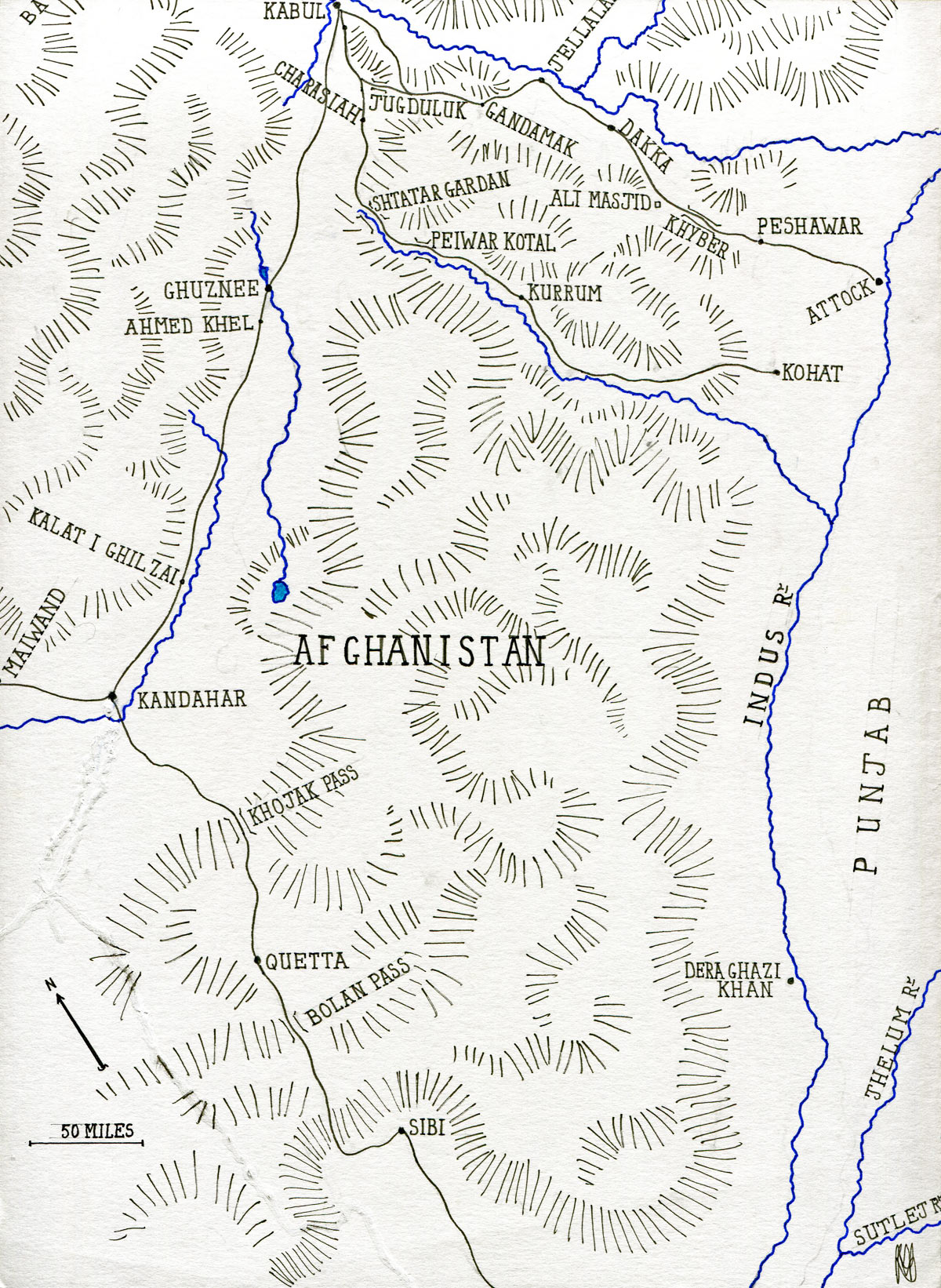

Place of the Battle of Kabul 1842: Afghanistan

Combatants at the Battle of Kabul 1842: British and Indian troops (of the Bengal and Bombay Armies) against Afghan levies and tribesmen.

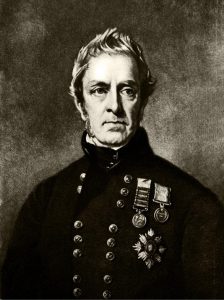

Commanders at the Battle of Kabul 1842: General George Pollock and Brigadier Nott against Akhbar Khan and a number of Afghan leaders and tribal chiefs.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Kabul 1842: General Pollock’s army numbered 8,000 men. Brigadier Nott’s force numbered around 3,000 men. Afghan numbers varied widely across the country. In the advance up the Jugdulluk Pass, Akhbar Khan faced Pollock with some 15,000 men.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Kabul 1842:

The British infantry, wearing cut away red coats, white trousers and shako hats, carried the old Brown Bess musket and bayonet. The Indian infantry were similarly armed and uniformed.

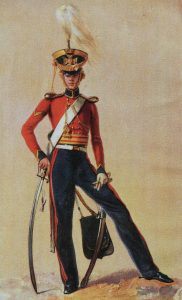

The Light Dragoons (Hussars) wore the standard hussar uniform of pelisse, dolman and shako rather than a busby, and were armed with swords and carbines.

The Afghan soldiers were dressed as they saw fit and carried an assortment of weapons, including muskets and swords. The Ghilzai tribesmen carried swords and jezails, long barrelled muskets.

Winner of the Battle of Kabul 1842: The British and Indians.

British and Indian Regiments at the Battle of Kabul 1842:

General Pollock’s army:

British:

3rd HM Light Dragoons (Hussars) now Queen’s Royal Hussars

9th HM Foot, later Norfolk Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment

13th HM Foot, later Somerset Light Infantry, later the Light Infantry and now the Rifles

31st HM Foot, later East Surrey Regiment and now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment

HM 9th Regiment marching into Allahabad after the First Afghan War: Battle of Kabul 1842 in the First Afghan War: print by Ackermann

Indian:

1st Bengal Light Cavalry

10th Bengal Light Cavalry

Two Regiments of Irregular Horse

6th Bengal Infantry

26th Bengal Infantry

30th Bengal Infantry

33rd Bengal Infantry

35th Bengal Light Infantry

53rd Bengal Infantry

60th Bengal Infantry

64th Bengal Infantry

Two batteries of Horse Artillery

Three batteries of Field Artillery

One battery of Mountain Artillery

Brigadier Nott’s army:

British:

40th HM Foot, later South Lancashire Regiment and now the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment

41st HM Foot, later the Welch Regiment and now the Royal Regiment of Wales

Indian:

3rd Bombay Cavalry

Skinner’s Horse

Regiment of Irregular Horse

16th Bengal Infantry

38th Bengal Infantry

42nd Bengal Infantry, later 5th Jat Light Infantry

43rd Bengal Infantry, later 6th Jat Light Infantry

12th Khelat-i-Ghilzai Regiment (of Shah Shujah)

Two batteries of Horse Artillery

Two batteries of Field Artillery

The First Afghan War:

The British colonies in India in the early 19th Century were ruled by the Honourable East India Company, a powerful trading corporation based in London, answerable to its shareholders and to the British Parliament.

In the first half of the century, France as the British bogeyman gave way to Russia, leading finally to the Crimean War in 1854. In 1839 the obsession in British India was that the Russians, extending the Tsar’s empire east into Asia, would invade India through Afghanistan.

This widely held obsession led Lord Auckland, the British governor general in India, to enter into the First Afghan War, one of Britain’s most ill-advised and disastrous wars.

Until the First Afghan War, the Sirkar (the Indian colloquial name for the East India Company) had an overwhelming reputation for efficiency and good luck. The British were considered to be unconquerable and omnipotent. The First Afghan War severely undermined this view. The retreat from Kabul in January 1842 and the annihilation of Elphinstone’s Kabul garrison dealt a mortal blow to British prestige in the East, only rivalled by the fall of Singapore 100 years later.

The causes of the disaster are easily stated: the difficulties of campaigning in Afghanistan’s inhospitable mountainous terrain with its extremes of weather, the turbulent politics of the country and its armed and refractory population, and, finally, the failure of the British authorities to appoint senior officers capable of conducting the campaign competently and decisively.

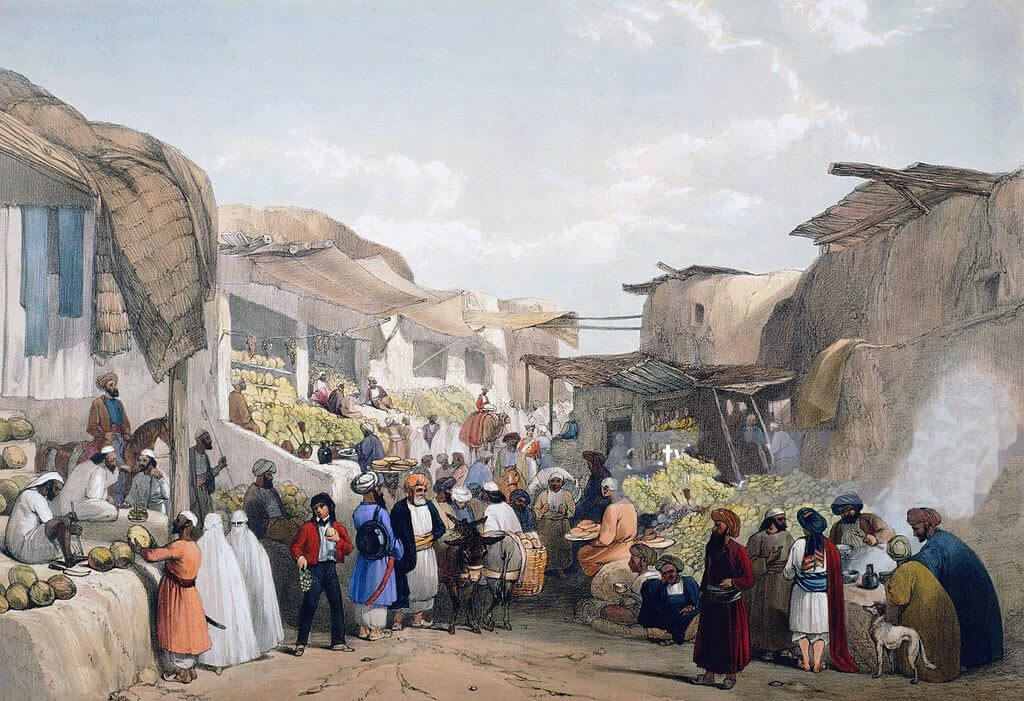

At the beginning of the war the substantially Hindu East India Company army crossed the Indus with trepidation, fearing to lose caste by leaving Hindustan, and appalled by the country they were entering. The troops died of heat, disease and lack of supplies on the desolate route to Kandahar, subject, in the mountain passes, to repeated attack by the Afghan tribes.

Once in Kabul, the Anglo-Indian army was reduced to a perilously small force, with many of the troops sent back to India, and left in the command of incompetents. As Sita Ram in his memoirs complained: ‘If only the army had been commanded by the memsahibs all might have been well.’

The disaster of the First Afghan War was a substantial contributing factor to the outbreak of the Great Mutiny in the Bengal Army in 1857, and, more immediately, led to wars in Sind, Gwalior and against the Sikhs in the Punjab.

The successful defence of Jellalabad and the progress of the Army of Retribution in 1842 could do only a little to retrieve the East India Company’s lost reputation.

Account of the Battle of Kabul 1842:

Learning of the massacre of the British and Indian Army retreating from Kabul in January 1842, the Governor General in Calcutta, Lord Auckland, rushed reinforcements across India to Peshawar, and appointed General George Pollock commander in chief of the relieving force, the first artillery officer to hold high command in a British Army.

Pollock reached Peshawar on 6th February 1842, to find the two brigades of Indian sepoys in a state of near disintegrated morale. It took months of encouragement and training to restore the regiments to a condition of battle readiness, all the while receiving pleas for help from Brigadier Sale, besieged in Jellalabad beyond the Khyber Pass.

In March 1842, a third brigade, consisting of cavalry, reached the army, a reinforcement that completed the restoration of the sepoys’ morale.

On 5th April 1842, Pollock’s army of eight infantry regiments, three cavalry regiments and two batteries of artillery, 8,000 men in all, marched out for the Khyber Pass.

Afridi tribesmen blocked the pass with a barricade of wood and thorns. Columns of Anglo-Indian infantry infiltrated along the peaks on either side of the barricade, while the artillery blasted grape shot into the thicket, causing the Afridis to abandon the barricade without a fight. That night, the army encamped beneath the recaptured strongpoint of Ali Masjid, the iconic feature at the top of the pass.

At about this time the Ameer left in Kabul by the British, Shah Shujah, was murdered by the Sirdars in his capital city, and his son, Futteh Jung, reluctantly and fearfully took the throne for a short time, before escaping to the British camp and surrendering to Pollock.

In the South of Afghanistan, Brigadier Nott had resolutely held Kandahar for many months, with a force maintained at a high level of efficiency and morale, in sharp contrast to the state of the dispirited and finally annihilated troops that marched from Kabul in January 1842.

In December 1841, Elphinstone despairing called for Brigadier Maclaren’s brigade to march from Kandahar to Kabul, but the Afghanistan winter had balked the journey and forced Maclaren to return to Kandahar, leaving Nott with a powerful and self-confident force.

In January 1842, Nott received the same message that Shah Shujah sent to Sale in Jellalabad, directing him to retreat to Indian. In marked contrast to Sale’s vacillations, Nott refused point blank.

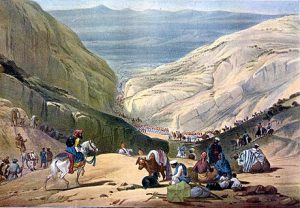

The British Army marching out of the mountains into Central Afghanistan: Battle of Kabul 1842 in the First Afghan War

In March 1842, news reached Kandahar of the surrender of the garrison in Ghuznee to the Afghans. Despite a guarantee of safe conduct, the Afghans massacred the sepoys and took the British officers prisoners, among them John Nicholson, later to earn fame at the Siege of Delhi during the Indian Mutiny.

Also in March 1842, Pollock’s force reached Jellalabad, where the garrison was found to have fought off the besieging Afghans. Pollock and Nott awaited instructions from the new Governor General in Calcutta, Lord Ellenborough, Pollock’s primary concern being to secure the release of the British prisoners from the Kabul garrison, still held by the Afghans.

Ellenborough’s initial order, sent in mid-May 1842, was for both forces to retreat to India, with the implication that the prisoners would be abandoned.

Before either force was ready to begin the withdrawal, Ellenborough, on 4th July 1842, varied his orders by permitting Nott to withdraw to India via Kabul and Jellalabad, and Pollock to withdraw via Kabul.

This was the wide discretion each general sought, and both rushed for Kabul.

Pollock fought two vigorous skirmishes on his way to Kabul, in one of which, at Huft Kotal, he inflicted a heavy reverse on Akhbar Khan and his army of 15,000 Afghan troops, before marching onto the old race course outside Kabul on 15th September 1842. For much of the route the troops were forced to march over the bones of their colleagues and their families, massacred and mutilated during the terrible retreat in January.

The progress of Pollock’s army was marked with the utmost savagery. Not for nothing was it named the ‘Army of Retribution.’ In areas known to have taken part in the massacre of the Kabul garrison, whole populations were slaughtered and villages burnt.

On 9th August 1842, Nott sent the greater part of his force back to India from Kandahar, via the southern route through Quetta, while he marched for Kabul with his two British battalions, his ‘beautiful sepoy regiments’ and his artillery.

On 28th August 1842, as Nott’s army approached Ghuznee, his cavalry was badly mauled in a bungled attack on an Afghan force.

On 30th August 1842, an army of 10,000 Afghans formed on the hills to the left of the Kabul road. Nott attacked and forced the Afghans off the battlefield with substantial losses.

Nott reached Ghuznee on 5th September 1842 and drove the Afghans out, before pillaging the town in revenge for the massacre of the sepoy garrison and the ill-treatment of the British officers.

It was the command of the new Governor General, Lord Ellenborough, that the army bring away a set of ornate gates, known as the Gates of Somnath, said to have been looted from India by the Afghans and hung at the tomb of Sultan Mohammed in Ghuznee. A sepoy regiment, the 6th Jat Light Infantry, was required to carry the gates back to India.

On 17th September 1842, Nott’s army reached Kabul to find, to his chagrin, Pollock there before him.

It was known that the British prisoners from the Kabul garrison were being taken west towards Bamian. Nott, on his march to Kabul, had refused to comply with the urgings of his officers to dispatch a force to Bamian. Pollock did send a force to Bamian, comprising Kuzzilibash Horse under Sir Richmond Shakespear. Brigadier Sale was sent with a force of infantry to support Shakespear, appropriately as Lady Sale was one of the prisoners.

Shakespear arrived at Bamian on 17th September 1842 to find the British prisoners had negotiated their own release and were in command of their prison and the surrounding area. Prisoners and escort arrived in Kabul on 21st September 1842 to a rapturous greeting. Before the British and Indian troops left Afghanistan for India there was still unfinished business.

The Kohistanees were known to have played a major part in the uprisings of December 1841 and January 1842, leading to the massacre of the Kabul garrison. A division from the ‘Army of Retribution’ conducted a foray into Kohistan, burning the capital Charikar to the ground, and massacring much of the population.

In Kabul, Pollock’s army destroyed the main bazaar on the basis that the heads of Macnaughten and Burnes had been carried through it after their murder in 1841.

On 12th October 1842, Pollock and Nott left Kabul with their troops and began the retreat to India via Gandamak, Jellalabad and Peshawar, destroying Jellalabad, Ali Masjid and many villages and towns on the way. Yet again the truth of Wellington’s words was demonstrated (‘It is easy to get into Afghanistan. The problem is getting out again.’) The Afghans harried the retreating troops along the route, particularly through the gorges of Jugdulluk and the Khyber Pass. In the final fighting, 60 of Nott’s force were killed before the British and Indians reached Peshawar.

Casualties at the Battle of Kabul 1842: British and Indian casualties were around 500 killed and wounded. Afghan casualties are unknown. Many thousands of Afghans were slaughtered in the reprisals.

Follow-up to the Battle of Kabul 1842:

Britain’s involvement in Afghanistan has always been dramatic and destructive; never more so than in the First Afghan War.

Captain Colin Mackenzie of the Madras Army in the Afghan costume he adopted to escape from captivity: Battle of Kabul 1842 in the First Afghan War

Britain had enough of Afghanistan after the terrible events of 1839 to 1842. The policy of the Government of India, particularly that of the ‘masterful inactivity’ of Lord Lawrence, kept the British out of Afghanistan for thirty years, until another lapse of good sense and restraint saw the outbreak of the Second Afghan War.

The gates in the toomb of Sultan Mahmud of Ghuznee, removed by Brigadier Nott as the ‘Gates of Somnath’: Battle of Kabul 1842 in the First Afghan War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Kabul 1842:

- The Gates of Somnath: In around 1025 AD, Mahmud of Ghuznee pillaged the Hindu Temple of Somnath, on the south-western Indian coast. Tradition had it that the Afghans removed the sandalwood gates of the shrine and took them to Ghuznee, where they were hung on Mahmud’s tomb. Lord Ellenborough, the Governor General, in an attempt to gain the approval of his Hindu subjects, directed that the gates be recovered and brought to India. In obedience to Ellenborough’s order, Nott’s men, during the pillage of Ghuznee in revenge for the massacre of its garrison, removed the gates. On hearing that his order had been complied with, Lord Ellenborough issued a declaration that the British, in recovering the gates, had wiped out a disgrace of 800 years standing. The 6th Jat Regiment carried the Somnath Gates back to India, where Ellenborough caused them to be paraded across the country in a special ceremonial car, before being returned in triumph to the shrine at Somnath. On examination, Hindu scholars rejected the idea that the gates were the originals taken from Somnath and they were relegated to the fort at Agra. No doubt there was unflattering comment made of the Governor General in the ranks of the 6th Jats.

- The Khelat-i-Ghilzai Regiment of the Shah Shujah’s service, on its arrival in India, was taken into the British service with that name and continues in the Indian Army.

- A battery of horse artillery in Shah Shujah’s army was also taken into the British Army, and continues as T Battery of the Royal Artillery, with the subsidiary name of Shah Shujah’s Battery.

- The East India Company issued a medal called the Candahar, Ghuznee, Cabul Medal to the troops of Pollock’s and Nott’s forces.

References for the Battle of Kabul 1842:

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes

Afghanistan from Darius to Amanullah by General McMunn

History of the British Army by Fortescue

The previous battle in the First Afghan War is the Siege of Jellalabad

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Moodkee