The battle in the Crimean War on 25th October 1854, that saw the Charge of the Light Brigade, the Charge of the Heavy Brigade and the Thin Red Line

Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Simpson

The previous battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of the Alma

The next battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of Inkerman

Battle: Balaclava

War: Crimean War

Date of the Battle of Balaclava: 25th October 1854

Place of the Battle of Balaclava: On the southern Crimean coast in the Old Tsarist Russian Empire.

Combatants at the Battle of Balaclava: British, French and Turkish troops against the Imperial Russian Army.

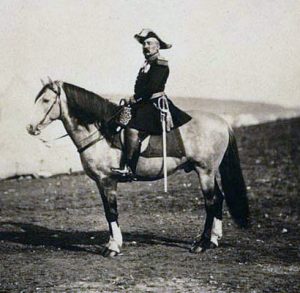

Major General Sir James Scarlett, commander of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Commanders at the Battle of Balaclava: Lieutenant General the Earl of Raglan commanded the British Army, General Saint-Arnaud commanded the French Army. Prince Menshikov commanded the Russian Army. The Russian commander of the Balaclava assault was General Liprandi, Menshikov’s second in command.

Lieutenant General Lord Lucan commanded the British Cavalry Division. Major General Lord Cardigan commanded the Light Brigade and Major General Sir James Scarlett commanded the Heavy Brigade. Major General Sir Colin Campbell commanded the 93rd Highlanders.

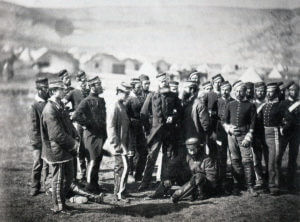

Officers of the French Chasseurs d’Afrique: Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Balaclava: The armies that fought in the Crimean War for Russia, Britain and France were in organisation little different from the armies that fought the Napoleonic wars at the beginning of the century. They were however on the verge of substantial change, brought about by developments in firearms.

The British infantry fought with the Brown Bess musket in some form from the beginning of the 18th Century.

As the Crimean War broke out, the British Army’s infantry was being equipped with the new French Minié Rifle, a muzzle loading rifle fired by a cap (all the British divisions, other than the Fourth, arriving in the Crimea with this weapon). This weapon was quickly replaced by the more efficient British Enfield Rifle.

The new rifle was sighted up to 1,000 yards, as against the old Brown Bess, wholly inaccurate beyond 100 yards.

It would take the rest of the century for field tactics to catch up with the effects of the modern weapons coming into service.

93rd Highlanders, the ‘Thin Red Line’, at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Winner of the Battle of Balaclava: Balaclava is a battle honour for all the British regiments that took part. It is usually a pre-condition for a British regimental battle honour that the battle was a victory for British arms. Balaclava was a strategic defeat. The Russians captured seven guns and at the end of the battle held the ground they had attacked. Against this, the three episodes in the battle; the Charge of the Heavy Brigade, the Thin Red Line and the Charge of the Light Brigade, are such icons of courage and achievement for the British Army, that it is not surprising the military authorities awarded Balaclava as a battle honour to the regiments involved.

13th Light Dragoons: Battle of Balaclava on 15th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Michael Angelo Hayes

British Regiments at the Battle of Balaclava:

4th Dragoon Guards: now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

5th Dragoon Guards: now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

1st Royal Dragoons: now the Blues and Royals.

Royal Scots Greys: now the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

6th Inniskilling Dragoons: now the Royal Dragoon Guards.

4th Light Dragoons: now the Queen’s Royal Hussars.

8th Hussars: now the Queen’s Royal Hussars.

11th Hussars: now the King’s Royal Hussars.

13th Light Dragoons: now the Light Dragoons.

17th Lancers: now the Queen’s Royal Lancers.

93rd Highlanders: later the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and now the Royal Scots.

All these regiments have Balaclava as a battle honour.

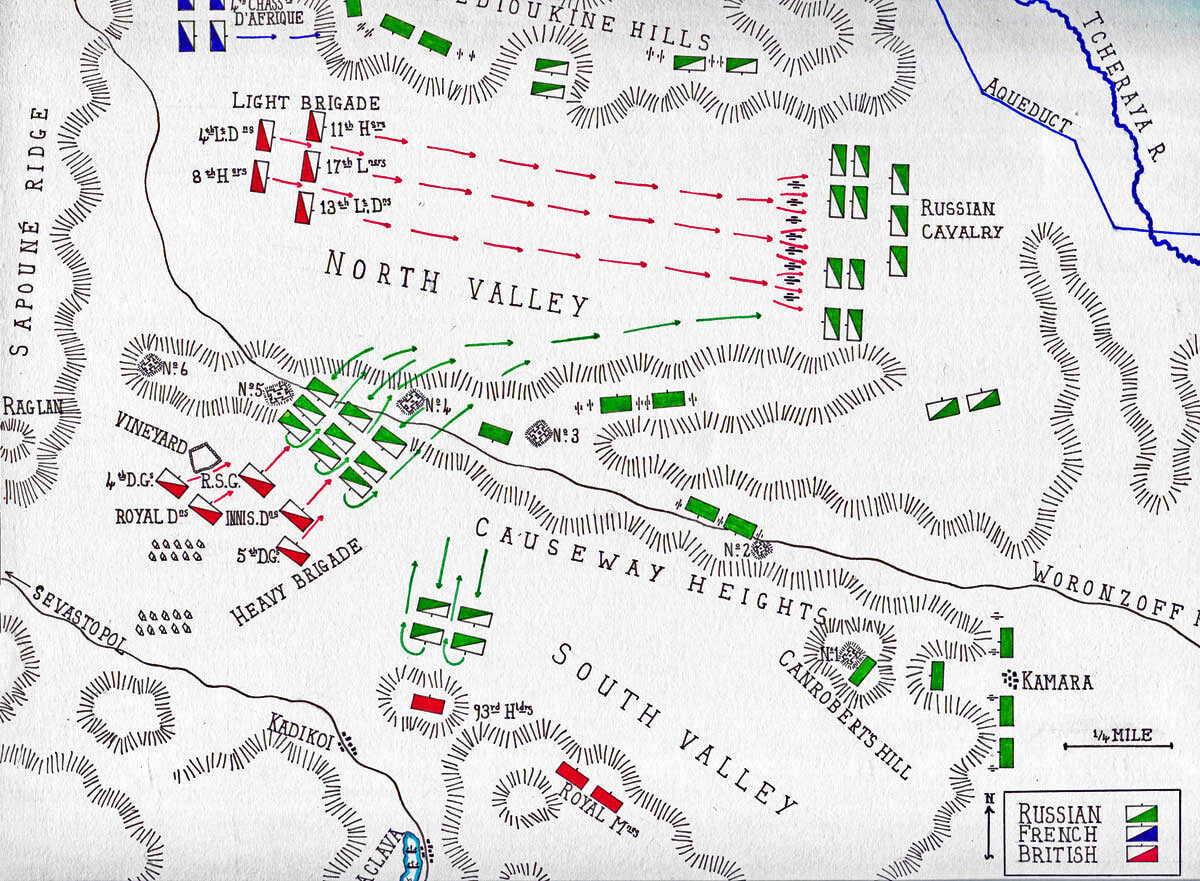

(this map appears in the bestselling book, The Dangerous Book for Boys

by Gonn Iggulden and Hal Iggulden, in the section Famous Battles-Part Two)

Account of the Battle of Balaclava: In mid-September 1854, the British and French armies, with a small Turkish contingent, landed on the western Crimean coast, 30 miles north of Sevastopol, with the aim of capturing this important Russian Black Sea city and naval base.

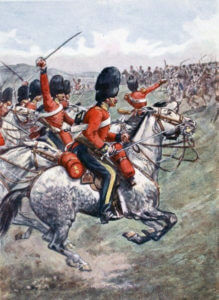

4th and 5th Dragoon Guards of the British Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

The allied armies marched south along the coast and fought the battle of the Alma on that river, defeating the Russian army and driving it back towards the city.

British cavalry in the Crimea: Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

Lord Raglan and Marshal St Arnaud, the two commanders-in-chief, resolved to march around the inland side of Sevastopol and begin siege operations against the city from the south. Once the march was completed, the French established their base at Kamiesh, on the south-western tip of the Crimea, south of Sevastopol, while the British took Balaclava as their base, fifteen miles along the coast to the east.

The Russian commander, Prince Menshikov, marched his army out of Sevastopol to the north-east, leaving a garrison to conduct the defence of the city. The allies were thereby left with two tasks; the siege of the city and holding off Menshikov’s army. During October 1854, reinforcements came in to Menshikov’s army from elsewhere in the Crimea and further afield in Russia, until his army was larger than that of the allies.

On 25th October 1854, Menshikov launched an assault across the Tchernaya River to the north-east of Balaclava, with the aim of capturing the British base. The assault was commanded by his deputy, General Liprandi.

Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Henri Dupray

Liprandi crossed the Tractir Bridge over the river and advanced on the positions held by Turkish troops along the Causeway Heights. Liprandi commanded twenty-five battalions of infantry, twenty-three squadrons of cavalry, thirteen squadrons of Cossack light horse and sixty-six guns. Supporting General Liprandi, by occupying the Fedioukine Hills, was a further force commanded by General Jabrokritski, of seven battalions and fourteen guns. The total force comprised 20,000 infantry, 3,500 cavalry and 76 guns.

Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Henri Dupray

British cavalry in the Crimea: Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

The Woronzoff Road, running along the ridge of the Causeway Heights, provided an important communication for the British, being the only firm road from Balaclava up to the siege works at Sevastopol. The Turkish troops were building six redoubts along the Heights, to protect the road and defend Balaclava. The work was not far progressed. Nine 12 pounder naval guns bolstered these positions. After a heavy bombardment, the Turkish troops were driven out of the Number One redoubt on Canrobert’s Hill, suffering some 400 casualties of a garrison of 500.

Lord Raglan, from his headquarters on the Sapouné Heights to the west, saw the threat to Balaclava and his lines of communication. The only British troops between the Russian force and the port were the two British cavalry brigades, the Heavy Brigade and the Light Brigade, which had their encampments in the valley, the 93rd Highlanders and a small force of marines.

8th Hussars: Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Ackermann

Raglan ordered the Second and Fourth British Divisions to march down from their camps outside the Sevastopol siege lines, to support the cavalry and highlanders. There was considerable delay in persuading the divisional commanders to make the arduous journey down to the valleys at Balaclava. Many of the regiments had spent the night in the trenches and were exhausted and, only days previously, a similar order had caused the infantry to make just this march, to find it was a false alarm.

Following the Russians’ successful attack on the Turkish troops in Number One Redoubt, the garrisons of the other earthworks left their positions and made for Balaclava. Some of the Turkish soldiers were belaboured by a Scottish soldier’s wife, armed with a frying pan, as they fled through the camp of the 93rd Highlanders.

Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Stanley Berkeley

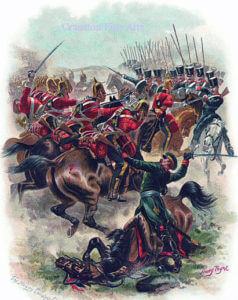

The Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava:

As the Russian infantry and guns pushed the Turks out of the redoubts, a force of 3,000 Russian cavalry moved from the North Valley onto the Causeway Heights, with the intention of advancing across the South Valley to occupy Balaclava. At the same time the British Heavy Brigade, of 900 cavalrymen commanded by Major General James Scarlett, was moving eastwards into the South Valley. The main section of the brigade comprised six squadrons of the Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons), the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons and the 5th Dragoon Guards, in two columns. Following these columns were the 1st Royal Dragoons and the 4th Dragoon Guards, another four squadrons.

Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Godfrey Douglas Giles

Lord Raglan and his staff on the Sapouné Heights, looking down from the high ground, could see the two cavalry forces converging. The Russians and the Heavy Brigade could not see each other, until the Russian cavalry came over the Causeway Heights and began their descent into the South Valley. In front of them, marching across their line of advance, was the Heavy Brigade.

General Scarlett acted immediately, forming his left column into line and leading them into the attack on the Russian cavalry force. The squadrons of the other column followed as a second line and the Royals and 4th Dragoon Guards hurried up to join the attack as quickly as they could.

Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

Inniskilling Dragoons in the Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Harry Payne

Trumpeter 11th Hussars: Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Harry Payne

As the Heavy Brigade charged, the Russian cavalry force halted, so that it received the Heavy Brigade charge stationary. The Russian commander appeared to be seeking to extend his line, after crossing the Causeway Heights. The first line, of Scots Greys and Inniskillings, struck the Russian cavalry, followed by the second line, of Inniskillings and 5th Dragoon Guards.

The wings of the Russian formation closed in behind the two lines of British horsemen and the Royal Dragoons charged the wings in the rear. The two forces struggled on the hillside, until the 4th Dragoon Guards came up and delivered a further charge into the Russian flank. In Hamley’s words, ‘Then -almost as it seemed in a moment, and simultaneously- the whole Russian mass gave way, and fled, at speed and in disorder, beyond the hill, vanishing behind the slope some four or five minutes after they had first swept over it.’

Panoramic view of the scene of the Charge of the Heavy Brigade in the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: water colour by Lieutenant Colonel Dawkins of the Coldstream Guards

In the rush to charge the Russians, the brigade commander, General Scarlett, with his a.d.c. Lieutenant Alick Elliot, his trumpeter and orderly, outstripped the line of troopers and plunged into the Russian ranks, initially alone. Scarlett suffered five wounds and Elliot fourteen wounds.

Lord Raglan sent down the message to Scarlett ‘Well done’.

The Thin Red Line tipped with steel: 93rd Highlanders at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Robert Gibb

The Thin Red Line at the Battle of Balaclava:

As the force of Russian cavalry came over the lip of the Causeway Heights, before engaging the Heavy Brigade, a force of four squadrons detached from the main body and headed directly towards Balaclava. In their path stood the 93rd Highlanders under Sir Colin Campbell, the commander of the Highland Brigade. Two Turkish battalions fled as the Russians advanced.

As the Russians approached, Campbell brought the 93rd from concealment and formed line across the cavalry’s line of advance. The staff on Sapouné Hill saw what William Russell, the Times correspondent, described as a ‘thin red line tipped with steel’ (in his initial report the expression used was ‘a thin red streak…’)

The Thin Red Line tipped with steel: 93rd Highlanders at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Hamley reports that the 93rd fired one volley at extreme range (around 900 yards) and the Russian cavalry withdrew. Other authorities state that the highlanders fired a second volley, also at considerable range.

The unyielding presence of the single Highland regiment caused the Russians to abandon their intention of taking Balaclava.

Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Christopher Clark

The Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava:

While the Heavy Brigade engaged the Russian cavalry force in the South Valley, the Light Brigade was in position at the western end of the North Valley.

Following its defeat by Scarlett’s brigade, the Russian cavalry re-crossed the Causeway Heights into the North Valley, presenting an opportunity for the Light Brigade to attack them in flank and complete the rout begun by Scarlett’s charge.

13th Light Dragoons in the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by John Charlton

Lord Cardigan failed to take the opportunity, even though the officer commanding the 17th Lancers, Captain Morris, pressed him to attack and, in the light of Cardigan’s refusal, sought permission to charge with his regiment, a request Cardigan also refused. Morris returned to his position striking his thigh and saying, ‘What an opportunity we have missed’.

Charge of the Light Brigade (17th Lancers) at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

Captain Morris was an experienced cavalry soldier, having fought at the Battle of Aliwal and the Battle of Sobraon in the First Sikh War with the 16th Lancers.

This experience was of no significance to Lord Cardigan, himself devoid of prior wartime service and with a supreme contempt for ‘Indian officers’.

Raglan’s failure to commit the cavalry to offensive action in the campaign to date caused considerable frustration in the cavalry division and derision in the rest of the army. On the Bulganek and Alma Rivers, during the march towards Sevastopol in September 1854, Raglan had refused to permit the Light Brigade to attack, causing the army to give the divisional commander the nickname of Lord ‘Look-on’, attributing the division’s inaction to him.

17th Lancers in the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Richard Simkin

Now at Balaclava, in the absence of the infantry, the cavalry was required to play a major role. The Heavy Brigade had played its part in full. The opportunity was passing to the Light Brigade and Cardigan refused to act. There seems to be no doubting Cardigan’s personal courage. He claimed that Lucan, the Cavalry Division commander, had forbidden him to take offensive action.

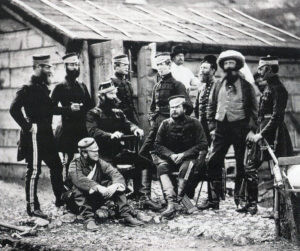

Officers of the 4th Light Dragoons in 1855: Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

The opportunity for the Light Brigade was particularly apparent to Raglan’s staff watching from the Sapouné Hills, amongst whom there was considerable excitement, particularly on the part of Captain Lewis Nolan of the 15th Hussars, General Airey’s a.d.c. a fine horseman and a ferocious advocate of the aggressive use of cavalry.

As the Russian cavalry force withdrew along the North Valley, to take up position behind a battery of eight guns at the far end, Raglan’s staff saw that the Russians on the Causeway Heights were preparing to remove the naval guns captured from the Turks in the redoubts. Loss of guns was a clear indicator of success or failure in battle and could not be allowed to go unchallenged. The two British infantry divisions had still not reached the valley floor, so that the only force available to prevent the removal of the guns was the cavalry division.

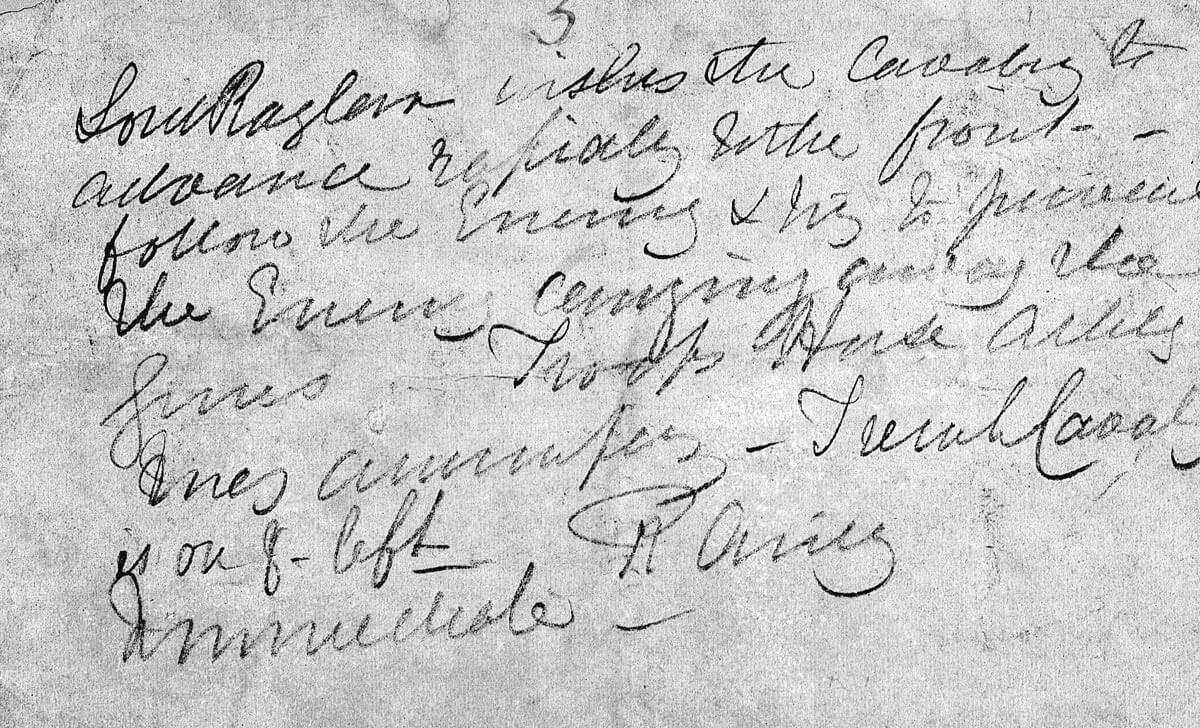

At Raglan’s direction, General Airey wrote the famous order to Lucan, stating: ‘Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop of horse artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left. Immediate.’

The order written by General Airey that launched the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Because of the urgency of the message and the difficulty in reaching the valley floor from the Sapouné Hills, the order was entrusted to Captain Lewis Nolan. The authorities agree this was an unfortunate choice. Hamley describes Nolan as ‘the author of a book on cavalry tactics, in which faith in the power of that arm is carried to an extreme.’

Nolan, a mercurial professional cavalry officer, who had begun his career in an Austrian hussar regiment, entertained a contempt for Lucan and was constantly irked by the failure to use the cavalry decisively.

Lord Cardigan leading the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Harry Payne

Nolan rode headlong down the steep slope and delivered Raglan’s order. The text made little sense to Lucan, as the preparations for the removal of the guns from the redoubts could not be seen from the valley floor. Lucan asked Nolan which enemy and which guns Raglan was referring to. Nolan is reported to have flung his arm out in the direction of the Russian cavalry force now positioned behind its guns at the end of the North Valley and to have said with some insolence, ‘There is your enemy. There are your guns, My Lord.’

The antagonism between the two men prevented any clarification of Raglan’s intention. Lucan was irked at being the butt of criticism for the inaction of the cavalry and was disinclined to have further discussion with the insolent Nolan. Lucan rode over to Cardigan and directed him to charge the Russian cavalry and guns at the end of the North Valley. After a brief remonstration, Cardigan ordered his brigade to mount and led it forward into the valley. Lucan added a final irritant for Cardigan by ordering the 11th Hussars, Cardigan’s regiment, into the second line.

Death of Captain Lewis Nolan in the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Thomas Jones Barker

Raglan’s staff watched, horrified, from the top of Sapouné Hill, as the Light Brigade moved off down the valley and failed to turn up onto the Causeway Heights. The staff could see the Russians positioned on the Fedioukine Hills, to the north side of the North Valley, with infantry, cavalry and guns, the original force of Russian cavalry attacked by the Heavy Brigade at the end of the North Valley, behind the battery of eight guns and, on the Causeway Heights on the south side of the valley, Russian infantry, cavalry and guns in the redoubts abandoned by the Turks. All these troops were ready to fire on the Light Brigade as it charged down the North Valley.

It was soon after 11am that the Light Brigade set off behind Lord Cardigan. The 13th Light Dragoons held the right flank of the first line with the 17th Lancers on the left. The 11th Hussars, Cardigan’s regiment, formed the second line, positioned behind the 17th Lancers. In the third line were the 8th Hussars and the 4th Light Dragoons.

Captain Godfrey Morgan of 17th Lancers on ‘Sir Briggs’ in the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Lord Lucan followed with the Heavy Brigade, but a short distance into the advance, as the scale of fire became apparent, Lucan halted the brigade and left the Light Brigade to continue down the valley alone.

Captain Nolan joined the ranks of the 17th Lancers, the officer commanding, Captain Morris, being a friend. It is thought Nolan realised the brigade was intended to ascend the Causeway Heights, not to attack down the valley and that a grave mistake was being made. Nolan rode across in front of Cardigan waving his sword. As he did so, he was struck and killed by a shell splinter, one of the first casualties.

The Relief of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

4th Queen’s Own Light Dragoons, one of the regiments of the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: print by Ackermann

The distance the Light Brigade had to cover to reach the guns was a mile and a quarter. Advancing at a trot, the brigade came under fire within a few minutes; shell fire, cannon balls and rifle fire from the flanking Russian forces striking down riders and horses. After five minutes, the brigade came within range of the eight guns at the end of the valley. These guns had a much easier target, firing at the brigade line, around 100 yards in width, rather than at its flank. Casualties spiralled, causing the regiments to increase their pace, until the lines were at the gallop and order was being lost. By the time the brigade reached the guns, half of its complement were casualties.

Reaching the end of the valley, the Light Brigade plunged into the Russian gun line and cut down those of the crews that had not fled. The 13th Light Dragoons, with the right-hand squadron of the 17th Lancers, struck the Russian battery directly. The left squadron of the 17th passed the battery and attacked Russian cavalry behind. The 11th Hussars also passed the battery and attacked the cavalry beyond, driving them back and pursuing them as far as the aqueduct. They were, in turn, pursued for some distance by a force of Russian cavalry and Cossacks.

French 4th Chasseurs d’Afrique attacking the Fedioukine Hills at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

The charge complete, the Light Brigade returned by the route it had come. The men did this singly or in small groups, other than two larger parties; one led by Colonel Shewell, formed of 70 men of the 8th Hussars and the 17th Lancers; the other, led by Lord George Paget, of 4th Light Dragoons and 11th Hussars. Each of these bodies was opposed by Russian cavalry, who emerged from the hills on either side of the valley and which they charged and dispersed.

The French General Morris directed the 4th Chasseurs D’Afrique, a colonial cavalry regiment, to attack along the Fedioukine Hills and silence the Russian fire on the north side of the valley. This they did with great success and a loss of only 38 casualties. Their charge relieved the British cavalrymen of the fire from the north side of the valley as they returned from the Russian battery.

Survivors from the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Lady Butler

Lord Cardigan, having ridden through the battery, found himself alone, turned and rode back down the valley. He was one of the first to reach British lines, where he met Sir George Cathcart. Cardigan is reported to have said ‘I have lost my brigade.’

On its return, the Light Brigade had a mounted strength of 195 officers and men from an original strength of 673. 247 men were killed or wounded. 475 horses were killed and 42 wounded. The 13th Light Dragoons mustered 10 mounted men.

The Light Brigade after the Charge at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Lady Butler

Although the First and Fourth British Infantry Divisions were now in the valley and ready to begin an assault on the Causeway Heights along the Woronzoff Road, no further action was taken. The Russians were left in control of the Heights and the road. The infantry divisions returned to their camps outside Sevastopol.

The Heavy Brigade suffered 92 casualties (9 killed) in the battle, some of whom were hit at the beginning of the charge down the North Valley.

Sergeant Ramage winning the Victoria Cross at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Harry Payne

Surgeon General Mouatt winning the Victoria Cross at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Victoria Crosses awarded to the regiments at Balaclava:

Royal Scots Greys: 2

6th Inniskilling Dragoons: 1

4th Light Dragoons: 1

11th Hussars: 1

13th Light Dragoons: 1

17th Lancers: 3

Casualties at the Battle of Balaclava:

Russian casualties are unknown.

Soldiers of the 13th Light Dragoons: Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: photograph by Fenton

British Casualties (killed, wounded and missing):

4th Dragoon Guards: 5 men

5th Dragoon Guards: 2 officers and 13 men

1st Royal Dragoons: 4 officers and 9 men

Royal Scots Greys: 4 officers and 55 men

6th Inniskilling Dragoons: 15 men

4th Light Dragoons: 4 officers and 55 men

8th Hussars: 4 officers and 53 men

11th Hussars: 3 officers and 55 men

13th Light Dragoons: 3 officers and 38 men

17th Lancers: 7 officers and 67 men

93rd Highlanders: no casualties.

Follow-up to the Battle of Balaclava:

The main consequence of the battle was that the use of the Woronzoff Road, important for communications between the British base at Balaclava and the siege lines outside Sevastopol, was lost to the British for the winter of 1854/1855, making the disastrous conditions even more difficult.

‘Sir Briggs’ the horse ridden by Captain Godfrey Morgan. later Lord Tredegar, of the 17th Lancers in the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Alfred Frank de Prades

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Balaclava:

- The Charge of the Light Brigade caused a sensation in Victorian Britain and throughout the world. It quickly became the stuff of legend, Lord Tennyson writing his famous poem: see below.

- Controversy has raged over the mistake that sent the Light Brigade down the valley, instead of up onto the Causeway Heights. Lord Lucan bore most of the blame. Hamley, who was present at the battle, questions the ambiguous wording of Raglan’s order. Without a doubt the extraordinary clash of personalities between Cardigan, Lucan and Nolan played a major part. The one unquestionable feature that emerges from the battle is the courage and persistence of the ordinary troopers and regimental officers of the cavalry regiments that fought at Balaclava. All the Crimean battles show the mid-Victorian British soldier to have been a very tough breed.

- The French General Bosquet, who was watching the Charge of the Light Brigade, is reported as saying ‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre’.

- The French 4th Chasseurs D’Afrique deserve great praise for their attack along the Fedioukine Hills, that relieved the retreating Light Brigade of further gun fire from one of the flanks.

- Among the various controversies, one is whether the charge was begun by a trumpet call and who sounded it. It seems likely that there was no call, just an order to mount, followed by the orders ‘Walk, March’. The pace increased inexorably as the Brigade moved down the valley.

- Franz Suppé’s overture ‘Light Cavalry’ is a tribute to the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava.

- The Royal Scots Greys were the lead regiment in the Charge of the Heavy Brigade. the Grey’s 2nd Squadron was led in the charge by Captain Samuel Toosey Williams. Captain Williams died in Scutari on 25th November 1854 of exhaustion and exposure, suffered in the period around the battle and the Great Storm of 15th November 1854. A memorial to this officer can be seen in the church at Buscot, Oxfordshire, where his parents lived.

Royal Scots Greys in the Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

Balaclava bugle carried by Trumpeter William Brittan of the 17th Lancers in the Charge at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

‘Forward the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns!’ he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!’

Was there a man dismayed?

Not though the soldier knew

Someone had blundered:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them

Cannon in front of them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

Flashed all their sabres bare,

Flashed as they turned in air

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wondered:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right through the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reeled from the sabre-stroke

Shattered and sundered.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came through the jaws of Death,

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

‘The Charge of the Heavy Brigade at Balaclava’ by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

October 25, 1854

I.

Bugle that sounded the Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

The charge of the gallant three hundred, the Heavy Brigade!

Down the hill, down the hill, thousands of Russians,

Thousands of horsemen, drew to the valley–and stay’d;

For Scarlett and Scarlett’s three hundred were riding by

When the points of the Russian lances arose in the sky;

And he call’d, ‘Left wheel into line!’ and they wheel’d and obey’d.

Then he look’d at the host that had halted he knew not why,

And he turn’d half round, and he bade his trumpeter sound

To the charge, and he rode on ahead, as he waved his blade

To the gallant three hundred whose glory will never die–

‘Follow,’ and up the hill, up the hill, up the hill,

Follow’d the Heavy Brigade.

1st Royal Dragoons: Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Ackermann

II.

The trumpet, the gallop, the charge, and the might of the fight!

Thousands of horsemen had gather’d there on the height,

With a wing push’d out to the left and a wing to the right,

And who shall escape if they close? but he dash’d up alone

Thro’ the great gray slope of men,

Sway’d his sabre, and held his own

Like an Englishman there and then.

All in a moment follow’d with force

Three that were next in their fiery course,

Wedged themselves in between horse and horse,

Fought for their lives in the narrow gap they had made–

Four amid thousands! and up the hill, up the hill,

Gallopt the gallant three hundred, the Heavy Brigade.

III.

Fell like a cannon-shot,

Burst like a thunderbolt,

6th Inniskilling Dragoons: Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Ackermann

Crash’d like a hurricane,

Broke thro’ the mass from below,

Drove thro’ the midst of the foe,

Plunged up and down, to and fro,

Rode flashing blow upon blow,

Brave Inniskillens and Greys

Whirling their sabres in circles of light!

And some of us, all in amaze,

Who were held for a while from the fight,

And were only standing at gaze,

When the dark-muffled Russian crowd

Folded its wings from the left and the right,

And roll’d them around like a cloud,–

O, mad for the charge and the battle were we,

When our own good redcoats sank from sight,

Like drops of blood in a dark-gray sea,

And we turn’d to each other, whispering, all dismay’d,

‘Lost are the gallant three hundred of Scarlett’s Brigade!’

4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards: Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Ackermann

IV.

‘Lost one and all’ were the words

Mutter’d in our dismay;

But they rode like victors and lords

Thro’ the forest of lances and swords

In the heart of the Russian hordes,

They rode, or they stood at bay–

Struck with the sword-hand and slew,

Down with the bridle-hand drew

The foe from the saddle and threw

Underfoot there in the fray–

Ranged like a storm or stood like a rock

In the wave of a stormy day;

Till suddenly shock upon shock

Stagger’d the mass from without,

Drove it in wild disarray,

For our men gallopt up with a cheer and a shout,

And the foeman surged, and waver’d, and reel’d

Up the hill, up the hill, up the hill, out of the field,

And over the brow and away.

5th Dragoon Guards: Charge of the Heavy Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War: picture by Ackermann

V.

Glory to each and to all, and the charge that they made!

Glory to all the three hundred, and all the Brigade!

Note.–The ‘three hundred’ of the Heavy Brigade who made

this famous charge were the Scots Greys and the 2nd squadron

of Inniskillings, with the remainder of the Heavy Brigade

dashing up to their support.

The ‘three’ were Scarlett’s aide-de-camp, Elliot, his trumpeter

and Shegog his orderly, who had been close behind him.

References for the Battle of the Balaclava:

Sir John Fortescue’s History of the British Army

British Crimean War Medal 1854 to 1856 with clasps for Balaclava and Sevastopol and the Turkish Crimean War Medal: Battle of Balaclava on 25th October 1854 in the Crimean War

The War in the Crimea by General Sir Edward Hamley

The Reason Why by Cecil Woodham-Smith

British Battles Volume III by James Grant

The previous battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of the Alma

The next battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of Inkerman