The first battle of the Crimean War, fought on 20th September 1854

Coldstream Guards at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Goojerat

The next battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of Balaclava

Lord Raglan, British commander-in-chief in the Crimea: the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

Battle: Alma

War: Crimean War

Date: 20th September 1854

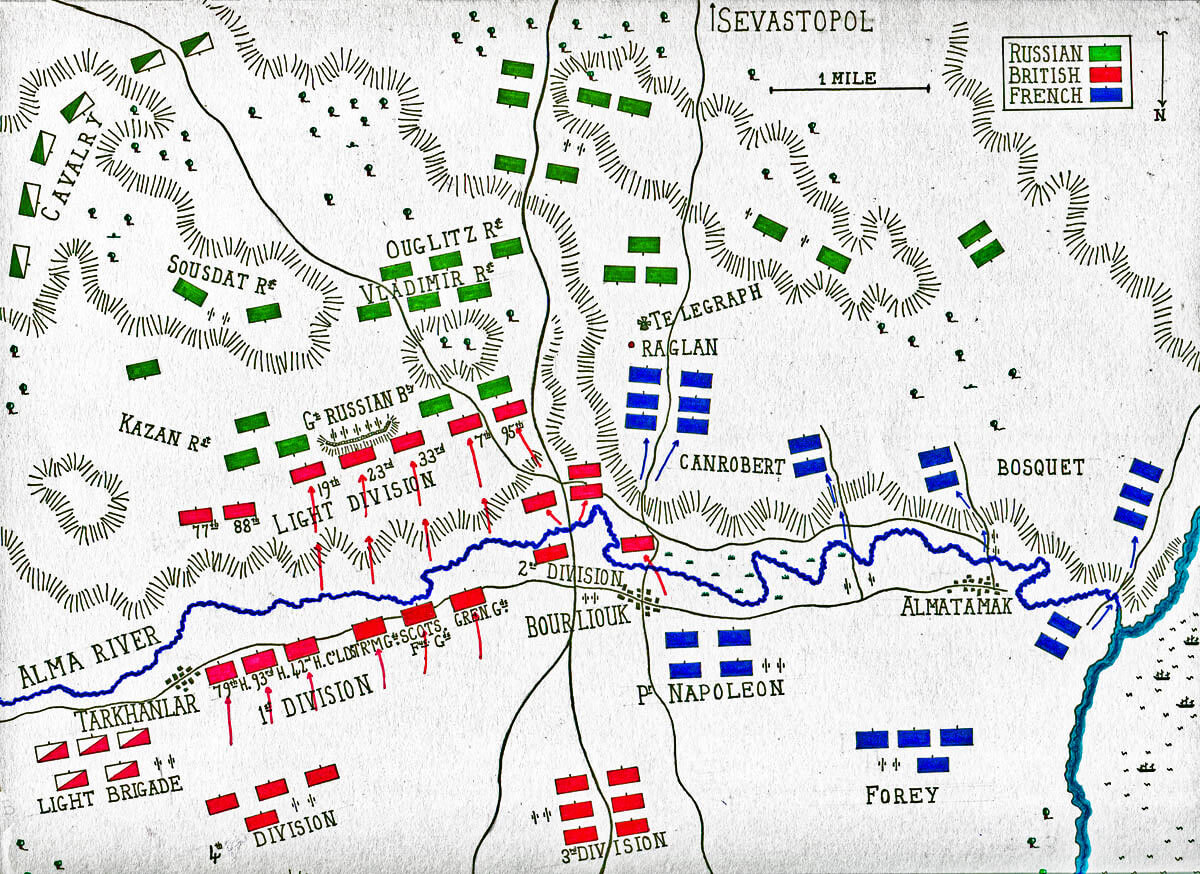

Place of the Battle of the Alma: On the west coast of the Crimea, to the north of Sevastopol

Combatants at the Battle of the Alma: British, French and Turkish troops against the Imperial Russian Army.

Generals at the Battle of the Alma: General the Earl of Raglan commanded the British Army. Marshal Saint-Arnaud commanded the French Army. Prince Menshikov commanded the Russian Army.

Size of the armies at the Battle of the Alma: The British Army comprised 26,000 infantry, 1,000 cavalry (only the Light Brigade; the Heavy Brigade did not land in the Crimea in time for the battle) and 60 guns. The French Army comprised 28,000 infantry, no cavalry and 72 guns. The Turkish contingent comprised 7,000 infantry, no cavalry and an unknown number of guns. The Russian Army was made up of 33,000 infantry, 3,400 cavalry and 120 guns.

Prince Menshikov, Russian commander-in-chief in the Crimea: the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of the Alma: The armies that fought in the Crimean War for Russia, Britain and France were in organisation little different from the armies that fought the Napoleonic wars at the beginning of the century. They were however on the verge of substantial change, brought about by developments in firearms.

The British infantry had fought with the Brown Bess musket in some form from the beginning of the 18th Century.

As the Crimean War broke out, the British Army’s infantry was being equipped with the new French Minié Rifle, a muzzle loading rifle fired by a cap (all the British divisions, other than the Fourth, arriving in the Crimea with this weapon). This weapon was quickly replaced by the more efficient British Enfield Rifle.

The new rifle was sighted up to 1,000 yards, as against the old Brown Bess, wholly inaccurate beyond 100 yards.

Marshal de Saint-Arnaud, French commander-in-chief at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

It would take the rest of the century for field tactics to catch up with the effects of the modern weapons coming into service.

Winner of the Battle of the Alma: The British and French

British Order of Battle at the Battle of the Alma:

Commander in Chief: Field Marshal Lord Raglan

The Cavalry Division: General the Earl of Lucan

Troop of Royal Horse Artillery

Light Brigade: Major-General the Earl of Cardigan

4th Light Dragoons

8th Hussars

11th Hussars

13th Light Dragoons

17th Lancers

First Division: the Duke of Cambridge

Two field batteries Royal Artillery

Guards Brigade: General Bentinck

3rd Battalion, Grenadier Guards

1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards

1st Battalion, Scots Fusilier Guards

Highland Brigade: Major General Sir Colin Campbell

42nd Highlanders

79th Highlanders

93rd Highlanders

Officer, NCO and piper of the 93rd Highlanders: the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

Second Division: Lieutenant-General Sir de Lacy Evans

Two field batteries Royal Artillery

Officers of the 49th Regiment: the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: print by Ackermann

Third Brigade: Brigadier-General Adams

41st Regiment

47th Regiment

49th Regiment

Fourth Brigade: Brigadier-General Pennefather

30th Regiment

55th Regiment

95th Regiment

Third Division: Lieutenant-General Sir Richard England

Two field batteries Royal Artillery

Fifth Brigade: Brigadier-General Sir John Campbell

4th King’s Own Royal Regiment

38th Regiment

50th Regiment

Sixth Brigade: Brigade-General Eyre

1st Royal Regiment

28th Regiment

44th Regiment

Fourth Division: Major-General Sir George Cathcart

One field battery of Royal Artillery

Seventh Brigade: Brigadier-General Torrens

20th Regiment

21st Royal Scots Fusiliers

68th Regiment

Eighth Brigade:

46th Regiment

(57th Regiment, which did not land until after the battle)

2nd Rifle Brigade leading the Light Division across the river at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Louis Johns

Light Division: Lieutenant-General Sir George Brown

One troop of Royal Horse Artillery and one field battery of Royal Artillery

2nd Battalion the Rifle Brigade.

First Brigade (known as the Fusilier Brigade): Major-General Codrington

7th Royal Fusiliers

23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers

33rd Regiment

Second Brigade: Major-General Buller

19th Regiment

77th Regiment

88th Regiment

The French order of battle at the Battle of the Alma:

The four divisions of General Bosquet, General Canrobert, Prince Napoleon and General Forey.

Account of the Battle of the Alma:

The British and French armies landed on the Crimean Peninsula on 14th September 1854, intending to capture the Russian naval base of Sevastopol in the south-west of the Crimea. The landing took place on the western Crimean coast some fifteen miles to the north of the port.

Royal Artillery on the move: Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

The road down the coast to Sevastopol crossed four rivers, flowing east to west into the Black Sea; the Bulganek, the Alma, the Katelia and the Belbeck.

The allied army (British, French and Turkish) began the march south from the landing site on 19th September 1854. The French army marched by the coast, with the Turkish contingent in its midst. The British in two columns took the inland flank. The British Light Brigade of cavalry provided a screen to the front and left flank. Ships of the British and French navies sailed parallel and in advance of the armies.

Marshal Saint-Arnaud at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: Saint-Arnaud was near to death from illness: picture by Belangé

A skirmish took place as the allied army crossed the Bulganek on the first day of the 25 mile march to Sevastopol. As the Russians withdrew from the hills beyond the river, Lord Lucan sought to pursue them with the Light Brigade, but was ordered to withdraw by Lord Raglan, the British commander-in-chief. The allied armies encamped on the high ground beyond the river.

French Artillery at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

It was on the River Alma that the Russian general, Prince Menshikov, resolved to make his stand, taking advantage of the high ground along the south bank.

The axis of the advance was the post road, following the coastline from Eupatoria in the north of the Crimea to Sevastopol. The country was open, rolling grassland, enabling the troops to march on either side of the road.

Coldstream Guards at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

On 20th September 1854, the allied armies continued their march in the same formation. At about midday, a warship, steaming in advance of the armies, opened a bombardment on the shore. The allied armies reached the top of one of the low ridges, that lay across the line of march and the valley of the Alma opened before them.

Three villages lay along the near bank of the river; Almatamak in front of the French; Bourliouk in the centre of the advance and Tarkhanlar to the left of the British. The post road crossed the Alma to the inland side of Bourliouk and ascended into the hills beyond the river.

French troops crossing the river at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

Along the high ground on the far side of the Alma lay the Russian Army in strength, intending to give battle in defence of Sevastopol. The main body of Menshikov’s force lay on Kourgané Hill in front of the British Army’s centre, covered by a battery of eight heavy siege guns at the front of its position. These guns were the focal point of the Russian defence and became known as the “Great Russian Battery” or the “Greater Redoubt”. Immediately beyond Bourliouk, the Russian reserves occupied a hill with a telegraph station, labelled Telegraph Hill. The post road to Sevastopol lay in the valley between Kourgané Hill and Telegraph Hill.

From Bourliouk to the coast, in front of the French line of advance, the south bank of the Alma became a cliff face. An accessible road crossed the river from Almatamak and ascended the cliff. Near the river mouth a steep path climbed the cliff face. The Russian presence on the high ground above this cliff was slight.

French Zouaves storming the heights at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

Menshikov’s leadership was uninspired and lacking in vigour. The Russians took little trouble to fortify their positions. The heavy guns on Kourgané Hill were fronted by a low parapet, intended to stop the guns from rolling down the hill rather than for protection. No works had been built to keep the French off the coastal high ground or to protect the Russian troops from naval bombardment.

French Zouaves at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Victor Adam

The Allied plan, agreed between Raglan and St Arnaud that morning was for the French to begin the attack under cover of the fleet’s guns.

Bosquet’s Division stormed up the coastal path and the Almatamak road. Canrobert crossed the Alma to the west of Almatamak and climbed Telegraph Hill, sending his guns up the Almatamak road. The Russian piquets set fire to Bourliouk and withdrew across the river and up the hill.

General St Arnaud sent word to Lord Raglan requesting that the British now launch their assault on the main Russian positions and Raglan issued the orders to his divisional commanders to attack.

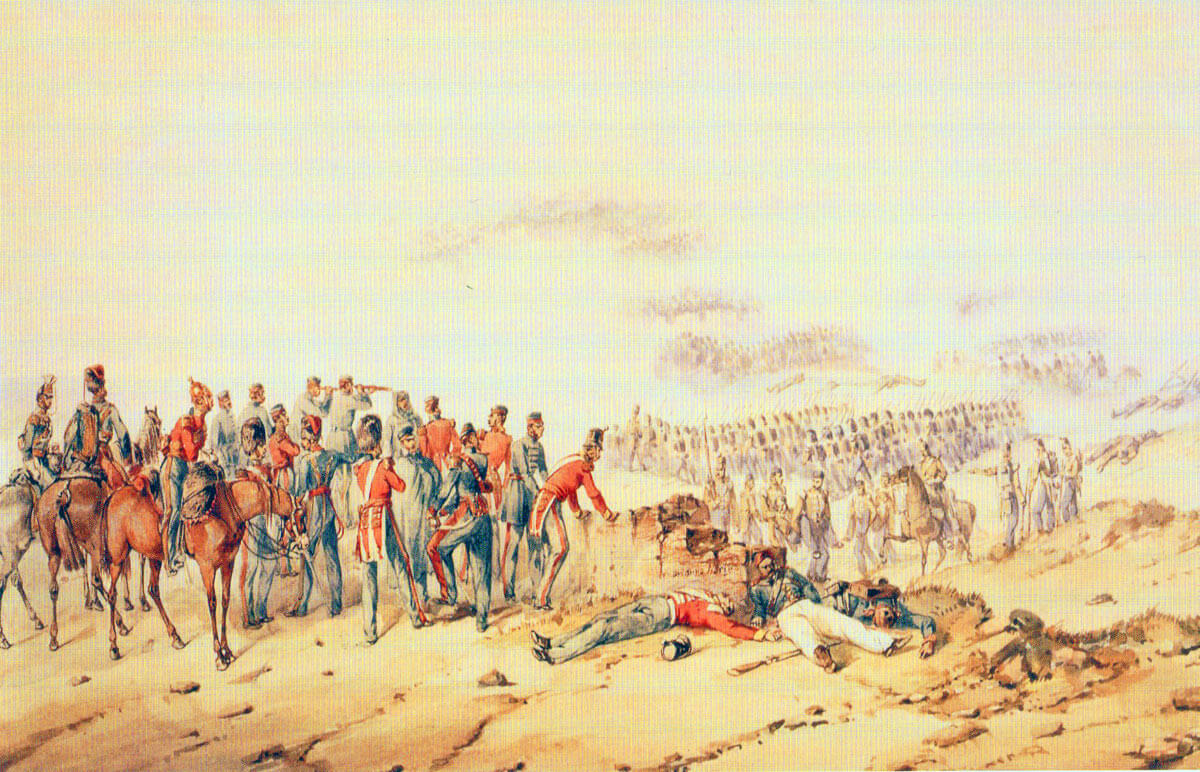

There now occurred an incident of extraordinary eccentricity. Leaving his generals to make the assault, Lord Raglan led his staff across the river and rode up onto a promontory below Telegraph Hill. Raglan watched the British attack from a position behind the Russian lines.

Duke of Cambridge with the Grenadier Guards in the background: Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: print by Ackermann

The British infantry advanced towards the river in a line stretching from Bourliouk nearly to Tarkhanlar; the Second Division on the right and the Light Division on the left. The Third Division supported the Second and the First Division supported the Light. The Fourth Division remained behind the left wing. The Light Brigade of cavalry guarded the inland flank.

The battery of heavy Russian guns on Kourgané Hill opened fire on the advancing British infantry with effect, inflicting casualties and disturbing the troops’ morale.

The burning village of Bourliouk caused considerable difficulty, the brigades of the Second Division being forced to bypass the village on either side to reach the river. The brigade of General Adams reached the river to the east of Bourliouk and found itself at the base of Telegraph Hill.

General Pennefather’s brigade passed to the west of the village. His third regiment, the 95th, joined Codrington’s Fusilier Brigade and took part in the assault with that formation, leaving Pennefather with the 30th and 55th Regiments.

French troops of Prince Napoleon’s division advance at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

Codrington’s regiments became the apex of the advance up to the Russian Battery. Two regiments of the Division’s second brigade were held back to protect the army’s inner flank. The remaining regiment of that brigade, the 19th, also joined Codrington’s attack so that he led forward five regiments rather than the three of his brigade (the 7th, 19th, 23rd, 33rd and 95th).

British Guards advancing at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Henri Dupray

The British infantry advanced to the river and began to cross, finding the water to be fordable at almost every point (it is not clear whether this fact had been discovered before the battle). The far side of the river comprised a steep six-foot bank which caused a halt in the advance, partly because of its physical obstruction and partly because it provided the troops with cover from the bombardment. The divisional commander of the Light Division, Sir George Brown, rode up the bank and urged his soldiers to follow. The division surged out of the river and scaled the hill beyond.

42nd Highlanders, the Black Watch, advancing behind Sir Colin Campbell at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

The ground on the hillside was terraced and walled, making it difficult for the regiments to reform after the river crossing and the British troops attacked up the hill in some disorder. The regiments reached the Russian Battery to find that the guns had been hastily limbered up and were being removed to the rear. It is the view of General Hamley, who served as an artillery officer in the Crimea, that the precipitous retreat of these guns saved the British infantry regiments from suffering appalling losses in the final stages of the assault, from discharges of case shot at short range.

Staff of the French commander-in-chief, Marshal Saint-Arnaud at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

Even so Codrington’s brigade was in a precarious position. There was little order and casualties were mounting, particularly among the officers. Large masses of Russian infantry were bearing down on the battery. Many of the British soldiers fell back down the hill towards the river.

Raglan’s position on the lower slopes of Telegraph Hill prevented him from exercising proper control over the assault by his army. If matters had gone according to plan, the First Division would have been on hand to support Codrington’s troops. It was not. The Duke of Cambridge was slow in ordering his brigades of Guards and Highlanders to cross the Alma. Fortunately, the Quartermaster General, Lieutenant General Airey had not accompanied his commander and was on hand to urge Cambridge forward. Even so the First Division was too far back to support the Light Division at the moment of crisis.

The First Division moved forward to the River Alma with General Bentinck’s Guards Brigade on the right and Sir Colin Campbell’s Highland Brigade on the left. The two brigades were formed, in accordance with precedent, with the senior regiments on the right within each brigade, the next senior regiment on the left and the junior regiment in the centre: from right to left the Grenadier Guards, the Scots Fusilier Guards, the Coldstream Guards, 42nd Highlanders, 91st Highlanders and the 79th Highlanders. The length of the line, substantially longer than that of the Light Division, extended beyond the Russian inland flank. Differences in the depth of the river and the height and steepness of the bank affected the speed with which these regiments were able to cross the river and begin the ascent of the hill.

British staff watching the advance of the Guards at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

The adjutant of the Grenadiers, Captain Higginson, described in his memoirs how his commander, Colonel Hood, noted the confused advance of the Fusilier Brigade as it attacked the Russian Battery and determined to keep his battalion under strict control. The Grenadiers formed in line, before leaving the river and advanced up the hill firing two volleys at the Russian infantry on the hillside, causing them to retreat.

Grenadier Guards attack up the hill after crossing the river at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

At the top of the hill, the 7th Royal Fusiliers, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Lacey Yea, on the right flank of Codrington’s brigade, had not retreated. Much of the rest of the brigade was falling back and the Scots Fusilier Guards in the centre of Bentinck’s brigade was largely swept back down the hill to the river by the flood of men.

The other two Guards battalions, the Grenadiers and the Coldstream, continued on up the hill and retook the Russian Battery. The 42nd Highlanders outstripping the other regiments of the Highland Brigade outflanked the Battery on the left; the other two Highland regiments coming up on the far flank.

Colours of the Scots Fusilier Guards at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Lady Butler

During the attack on the Russian Battery on Kourgané Hill, the remaining regiments of the Second Division, the 55th, 30th and 47th, attacked up Telegraph Hill, supported by the 41st and 49th.

British gun batteries crossed the bridge beyond Bourliouk and bombarded the Russian regiments on Telegraph Hill. A Royal Horse Artillery battery climbed up onto the hill and fired into the Russian infantry from the right of the Guards Brigade. Other British guns came up on the flanks of the regiments of the Second Division and fired into the retreating Russian regiments. In one instance a battery outstripped its gunners, following on foot, and the guns were brought into action by the officers.

The Third Division crossed the Alma in support of the Highland Brigade and the Light Brigade of cavalry moved forward on the inland flank.

Attack by the British infantry at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War

Cleared from the Battery and under threat from the attacks on Kourgané and Telegraph Hills, now fully supported by artillery fire, the Russian infantry fell back and left the battlefield, marching away towards Sevastopol.

The only allied cavalry on the field, Cardigan’s Light Brigade, under the direct command of the Cavalry Division commander, Lord Lucan, pressed for permission to pursue the retreating Russians, but were specifically ordered by Lord Raglan to remain with the army.

Black Watch at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

The allied armies camped beyond the battle field, while Menshikov led his army back along the post road to Sevastopol.

The French force took little part in the battle, although Bosquet’s division had contact with the Russians. Canrobert’s division in the centre made little use of its position to influence the attack on Kourgané Hill.

Casualties at the Battle of the Alma:

The Russians casualties were 5,709 killed, wounded and captured. The official French return claimed casualties of 1,340. The British belief is that this return was incorrect. Lord Raglan set French casualties at 560. 3 French officers were killed.

Scots Fusilier Guards on exercise in England in 1853: Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Orlando Norie

British casualties were set at 2,002 killed, wounded and missing.

British regimental casualties were:

Royal Artillery: 3 officers and 30 men.

Grenadier Guards: 3 officers and 127 men

Coldstream Guards: 2 offices and 27 men

Scots Fusilier Guards: 11 officers and 149 men

4th King’s Own Royal Regiment: 2 officers and 11 men

19th Regiment: 8 officers and 119 men

20th Regiment: 1 man

23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers: 13 officers and 197 men

30th Regiment: 5 officers and 74 men

33rd Regiment: 7 officers and 232 men

41st Regiment: 27 men

42nd Highlanders: 39 men

44th Regiment: 8 men

47th Regiment: 4 officers and 65 men

49th Regiment: 15 men

55th Regiment: 8 officers and 107 men

77th Regiment: 20 men

79th Highlanders: 9 men

88th Regiment: 1 officer and 21 men

93rd Highlanders: 1 officer and 51 men

95th Regiment: 17 officers and 176 men

Rifle Brigade: 1 officer and 50 men

Follow-up to the Battle of the Alma:

Colours of the 79th Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders: Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Michael Angelo Hayes

Raglan urged his French colleague, St Arnaud, that the allies should immediately follow the Russians into Sevastopol. St Arnaud refused to do so. It seems to be the authoritative view, particularly of the Russians, that if the allies had launched a prompt attack, they would have had little difficulty in taking the city. The delay enabled the Russians to recover from the defeat and put the city defences in proper order. This in turn condemned the allies to the winters of 1854/5 and 1855/6 in the siege of Sevastopol and to two further battles.

On the other hand, General Hamley, who served in the Crimea, states in his book that when the army did follow the Russians they found few signs of a disorderly retreat.

The battle revealed a number of stark failings in the British Army.

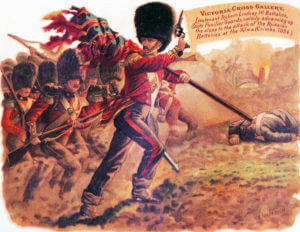

Lieutenant Lindsay of the Scots Fusilier Guards winning the Victoria Cross at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Harry Payne

There was no standard battle drill, each regiment’s conduct depending on the individual approach of the commanding officer. Some regiments felt it necessary to form line and advance methodically, while others rushed up to the Great Battery as quickly as they could, without forming up after crossing the Alma River.

There seems to have been little control at brigade or divisional level. There was no co-ordination between infantry and artillery, the guns being left to come up and open fire, as and where their officers thought best.

Due to his curious expedition behind the Russian lines, the commander in chief, Lord Raglan, lost control of his army. Hamley makes the comment: “It was fortunate in the circumstances, that the divisional commanders had so plain a task before them.” It is apparent that, however plain their tasks may have been, it was necessary for some control to be exercised. It fell to General Airey to take command of the assault, propelling the First Division into supporting the faltering Light Division attack.

Officer of the 79th Highlanders: the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: print by Ackermann

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of the Alma:

- All the Crimean battles are potent symbols for the British Army with many actions of valour by soldiers and officers and startling stupidity by the higher ranks.

- Victorian accounts of the retreat of the Fusilier Brigade from the Russian Battery describe a bugle call to retire as being the cause. General Hamley, in his account of the battle, makes no mention of this bugle call. It may well be that the causes of the retreat were the disorder of the regiments, the heavy officer casualties, the imminence of an overwhelming Russian attack and the lack of support from the First Division.

- Because of the nature of the attack on the Russian Battery and the importance of maintaining momentum, the use of the regimental colours has achieved prominence in the history and traditions of the battle. Important pictures show the Colours of the Scots Fusilier Guards being carried into battle, Sergeant Luke O’Connor with the Queen’s Colour of the Royal Welch Fusiliers and the Colour Party of the Coldstream Guards. Higginson states that the Colours of the Grenadier Guards were not uncased until just before the assault on the Russian Battery. He says the Colours of the Scots Fusilier Guards were shot through while the Grenadier Colours were largely unscathed.

- The Royal Welch Fusiliers’ Queen’s Colour was carried into battle by Ensign Henry Anstruther. Anstruther was shot dead, as the regiment stormed the Russian Battery. The Queen’s Colour was taken up by Sergeant Luke O’Connor and carried through the rest of the battle. O’Connor was subsequently commissioned and rose to the rank of Major General. O’Connor is said to be the only soldier to have served in every rank of the army to that level.

-

Captain Bell and Private Syle winning VCs at the Battle of the Alma on 20th September 1854 during the Crimean War: picture by Harry Payne

The battle gave rise to controversy over the conduct of the Scots Fusilier Guards. It seems likely that the regiment was pushed back down the hill by the retreat of the Fusilier Brigade. It is reported that the Grenadiers and the Coldstream called out “What’s happened to the Queen’s favourites now?” a reference to the regiment’s standing with Queen Victoria. There are additional criticisms that the regiment failed to re-form after crossing the river or to fix bayonets before advancing up the hill. The Scots Fusilier Guards seem to have begun their advance up the hill, before the Grenadiers and the Coldstream on each flank could clear the river and form up to the satisfaction of their commanding officers.

- Some of the poor decisions by British generals in the battle were attributed to their short sight. Higginson describes reaching the Battery and finding Sir George Brown sitting on his horse amid a hail of fire. Brown told him to press on. Higginson pointed out to the general there was a large Russian column moving towards them. Higginson says, “Sir George, being short of sight, had not seen this approaching column.” It is suggested in the authorities that a brigade commander on the left flank of the army was hampered in making decisions by poor eye sight.

- The French commander-in-chief, Marshal Saint-Arnaud, died soon after the Battle of the Alma. Saint-Arnaud forged his reputation in the fighting in North Africa, as France carved out her empire. He was instrumental in bringing Napoleon II to power.

- Several of the newly instituted Victoria Crosses were awarded for conduct at the Battle of the Alma. Captain Ball of the Royal Welch Fusiliers and Private Syle of the 7th Royal Fusiliers won crosses for capturing a Russian field gun during the battle.

References for the Battle of the Alma:

Sir John Fortescue’s History of the British Army

The War in the Crimea by General Sir Edward Hamley

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Goojerat

The next battle in the Crimean War is the Battle of Balaclava