Death of General Edward Braddock on the Monongahela River on 9th July 1755 in the French and Indian War

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Plassey

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is Braddock’s Defeat Part I

To the French and Indian War index

Battle : Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela River

War : The French and Indian War also known as the Seven Year War

(1757 to 1762)

Date : 9th July 1755

Place: The Monongahela River at the forks with the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers near modern Pittsburgh (Fort Pitt).

Combatants: Around 1,500 British and American troops (from Virginia, Maryland, North and South Carolina) against a force of 300 to 600 Indians (Ottawas, Miamis, Hurons, Delawares [Lenni Lenape], Shawnees and Mingoes [Iroquois]) and some 30 French colonial troops.

Winner: The Indians fighting for the French

British Forces:

30 Sailors from the Royal Navy under Lt Spendelowe

Sir Peter Halkett’s 44th Foot

Colonel Robert Dunbar’s 48th Foot

The following Independent Companies of Foot (part of the established British Army):

Captain Rutherford’s New York Company

Captain Horatio Gate’s New York Company

Captain Delamere’s South Carolina Company

Train of Royal Artillery (some 60 officers and men, six 12 pounders, six 6 pounders, 4 howitzers and around 30 coehorn mortars) commanded by Captain Orde

Captain Stewart’s Troop of Virginia Light Horse (around 28 troopers).

2 Companies of Virginian “Carpenters” commanded by Captains Polson and Mercer (each approx 3 officers and 50 sergeants, corporals, drummers and soldiers).

The only known portrait of Major General Edward Braddock. It is highly misleading as Braddock has been shown in an American general officer’s coat post American Revolution

It is not known which Indian chiefs were present on the French side but it is suggested that the Miami chief Pontiac and the Delaware “King” Shingas may have been present. The party of 10 to 16 Iroquois who accompanied the British Force was led by Scarouady (Monocatootha).

5 Companies of Virginian Rangers (troops raised for the campaign) commanded by Captains Stevens, Hogg, Waggoner, Cocke, and Perronee (each approx 3 officers and 50 sergeants, corporals, drummers and soldiers).

A company of Maryland Rangers commanded by Captain Dagworthy.A company of Rangers from North Carolina commanded by Captain

Edward Brice Dobson (son of Governor Brice Dobson).

A soldier of the 48th Foot on the march to Fort DuQuesne in Western Pennsylvania.

The British soldiers left their uniform coats in Alexandria and marched in their waistcoats.

(Illustration by Mark Dennis of Petaluma and St Andrews).

Note: It is not entirely clear from the contemporary accounts which of the American companies were present at the battle as there was movement between the main army and Dunbar’s rear party in the escorting of supplies. It can be definitely said that Polson’s and Perronee’s companies were present as part of the working party under Sir John Saint Clair. It is likely that Waggoner’s and Stevens’ companies were present.

44th Foot later the Essex Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment 48th Foot later the Northamptonshire Regiments and now the Royal Anglian Regiment

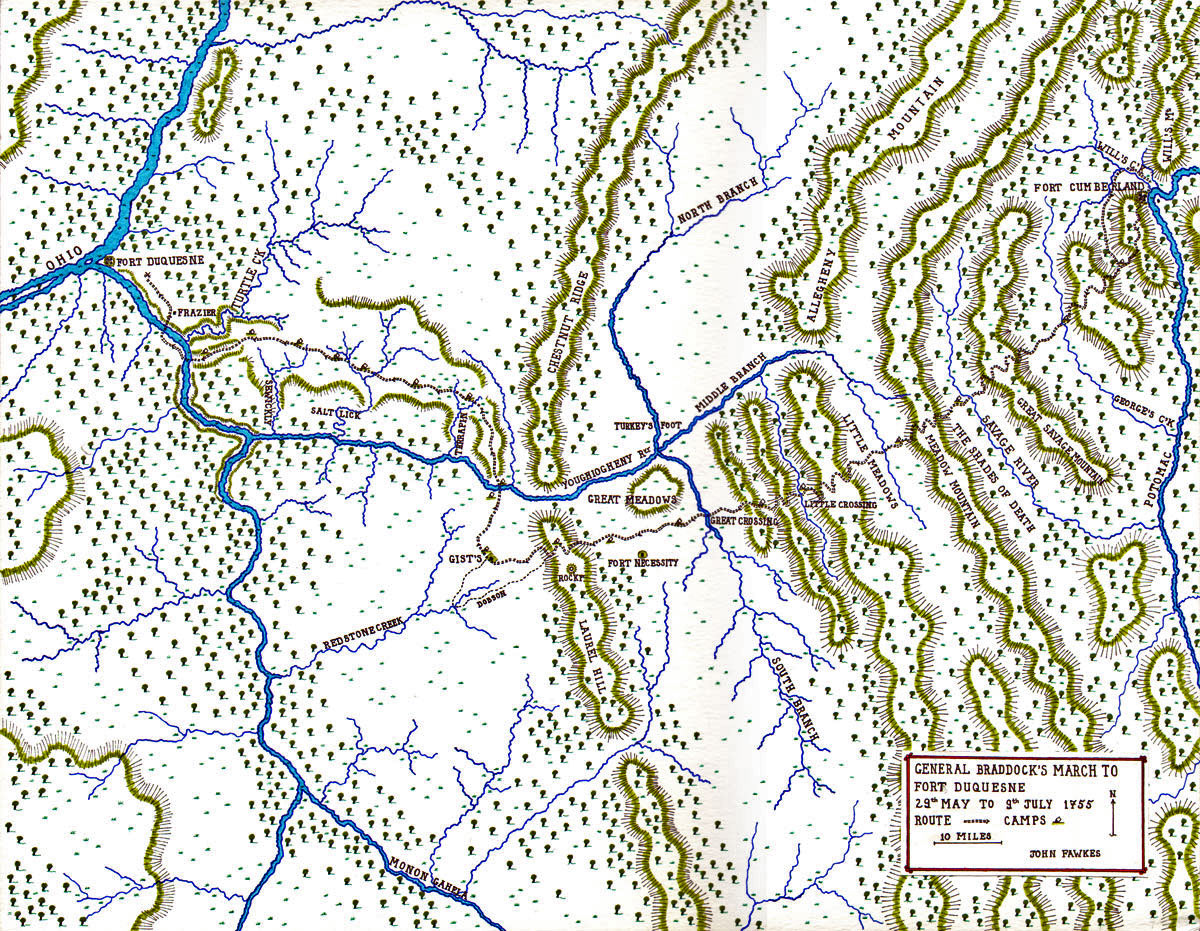

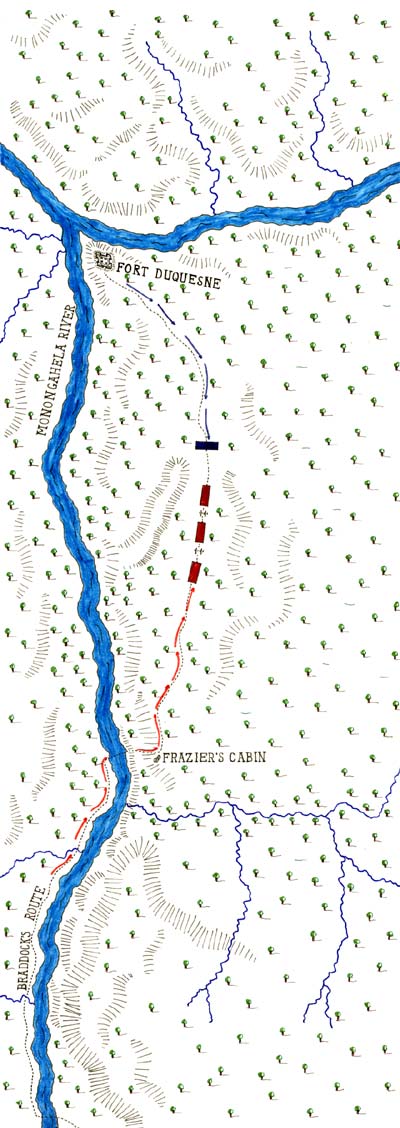

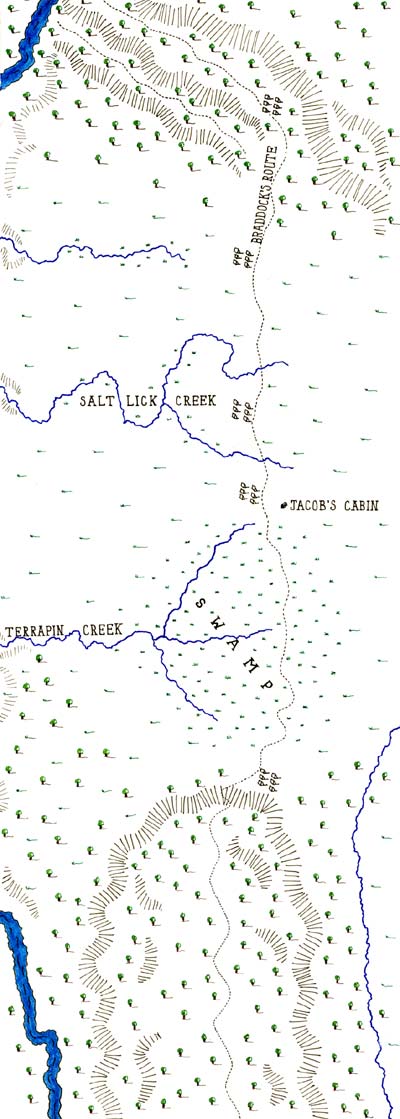

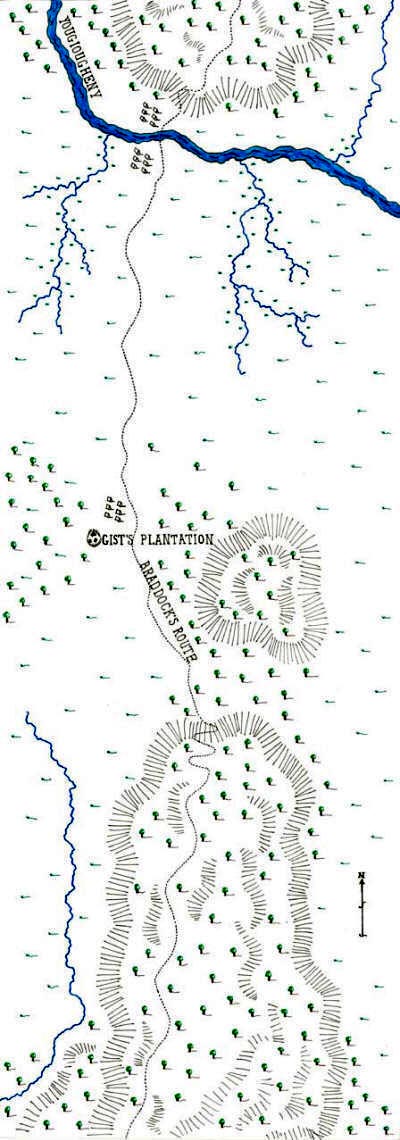

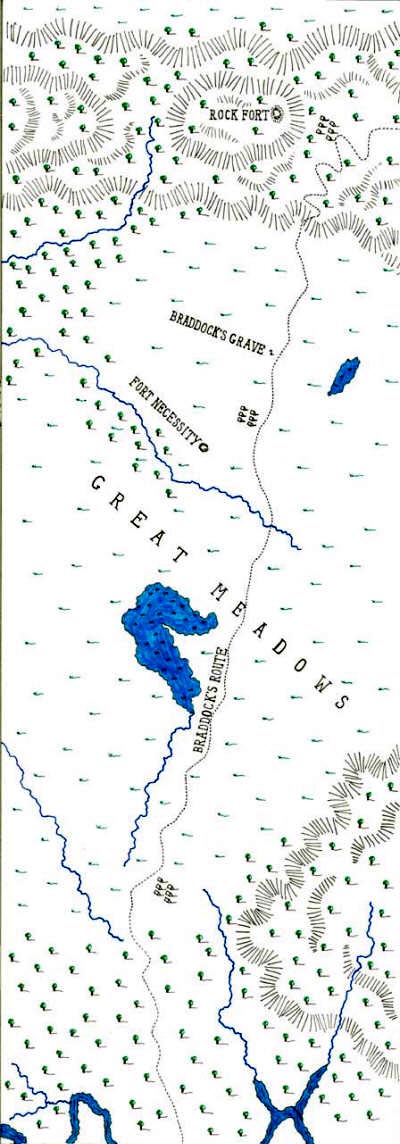

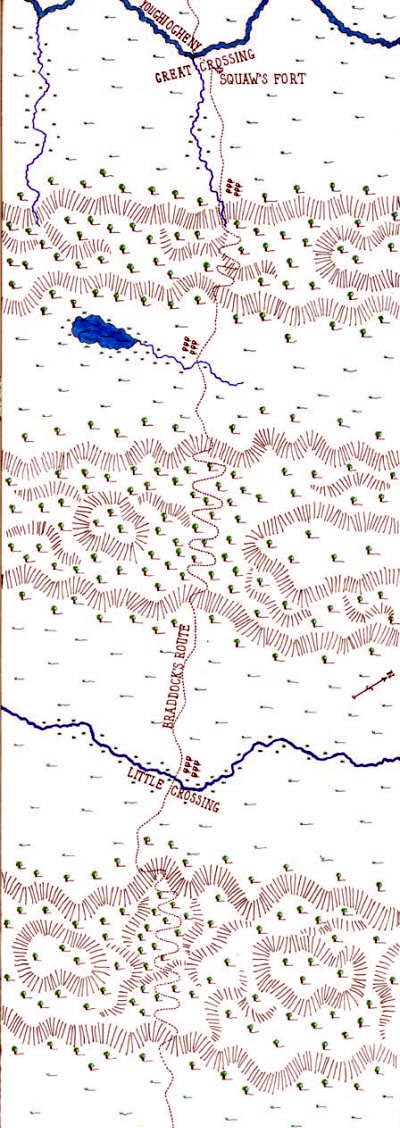

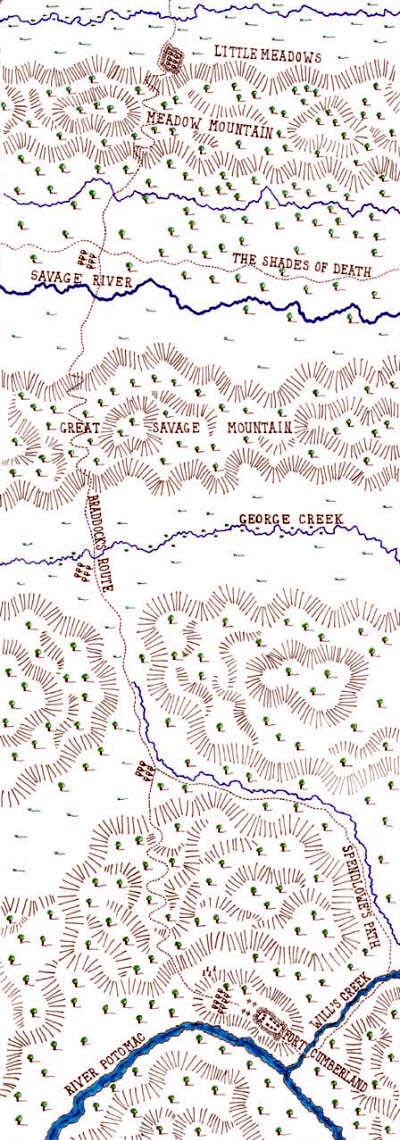

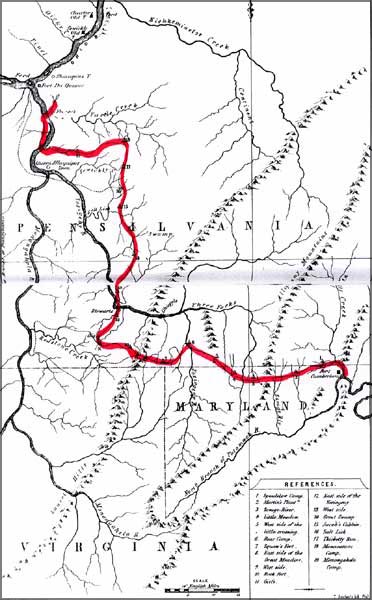

Contemporary map showing the route taken by General Braddock’s army to the Ohio Forks. Map used by Orme in his report of the campaign to the Duke of Cumberland.

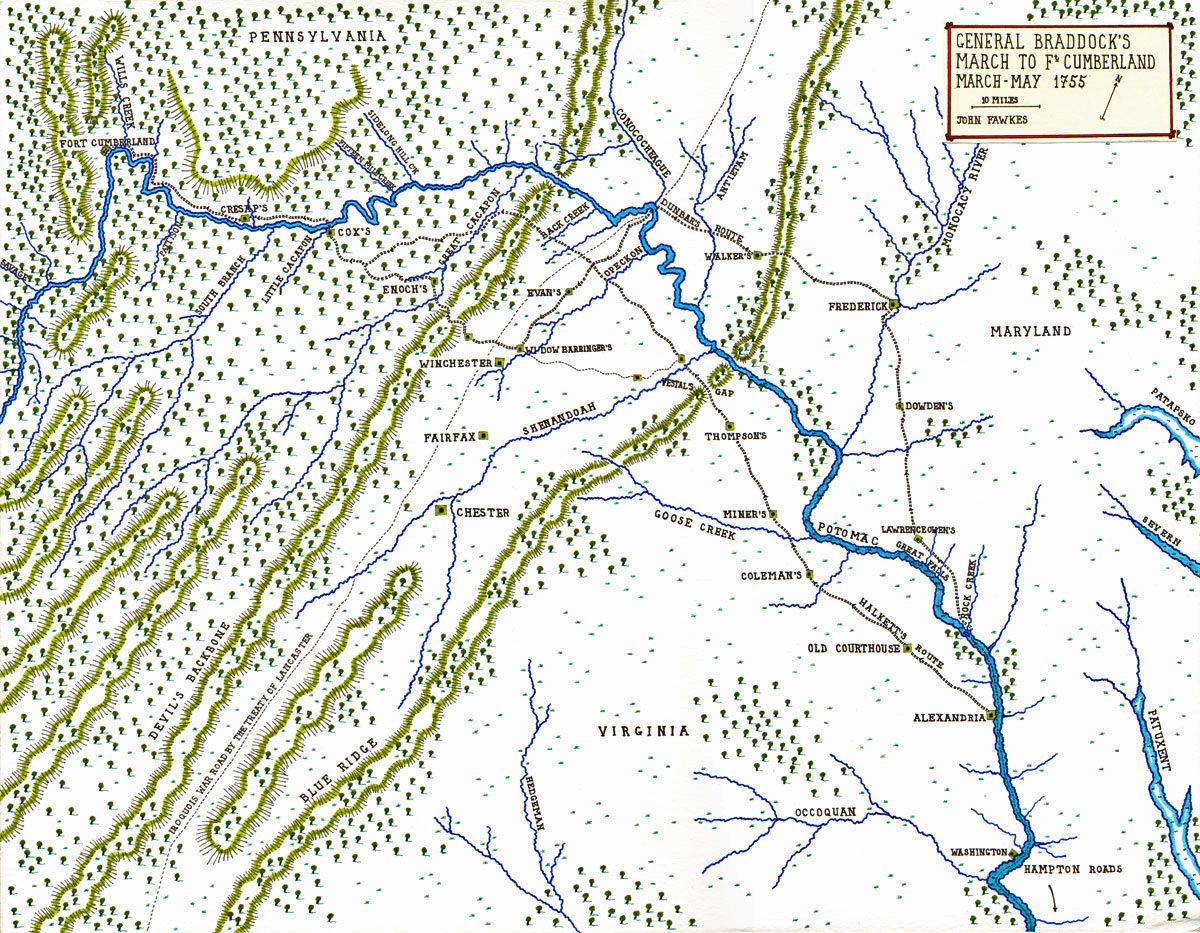

General Braddock’s March to Fort Cumberland through the Northern Neck of Virginia and through Maryland – March – May 1755 – Map by John Fawkes

Generals: General Edward Braddock commanded the British force and Monsieur Langlade and Monsieur de Beaujeu and Monsieur Dumas commanded the French and Indian force.

Account:

The origins for the march to the Monogahela lie in the establishment by the French of Fort Duquesne at the Ohio Forks (now Pittsburgh) and the small scale fighting during 1753 and 1754 culminating in George Washington’s capitulation at Fort Necessity on 3rd July 1754.

Robert Dinwiddie, the deputy governor of Virginia agitated for a force from England to displace the French on the Ohio. The Duke of Cumberland, Captain General of the British Army and the British Government were keen to precipitate a full war with the French in North America. General Edward Braddock lacked command experience. Braddock was influenced by a group of young officers headed by his aide de camp Captain Robert Orme. Orme had served with Braddock in the Coldstream Guards, the regiment in which Braddock had spent most of his service.

The expedition was marked by administrative incompetence at every level. It was not appreciated that Virginia did not have the necessary resources of provisions or transport. Braddock compounded his problems by insulting and ignoring the advice of his senior officers. The expedition would have foundered completely without the help of Pennsylvania through the agency of Benjamin Franklin in providing the minimum adequacy of horses and wagons.

George Washington in the uniform of the Virginia Regiment

It would have been more appropriate for the expedition to approach Fort Duquesne through Pennsylvania which had the necessary resource and a more direct route. Dinwiddie and other prominent Virginians were concerned that the road be built by Braddock’s advancing army through Virginia in the interests of the Ohio Company in which they had interests.

Two British regiments, Halkett’s 44th and Dunbar’s 48th on the Irish establishment were assigned to the Expedition. King George II refused to release regiments from England. The regiments were at less than half the necessary strength, each having 350 men. Drafts from other regiments brought them to 500. On arrival in Virginia locally recruited men brought the strengths to 750. The colonels of the regiments, Sir Peter Halkett and Robert Dunbar were unenthusiastic participants.

The fleet carrying the two regiments and a strong train of Royal Artillery arrived at Hampton, Virginia, in late March 1755. The troops were disembarked in the newly built town of Alexandria and went into camp. The three weeks in camp were marked by extreme indiscipline. Drunkenness was rife and the locals were pillaged by the troops. In mid-April the two regiments marched west for Will’s Creek in Maryland beyond north-western corner of Virginia from where the expedition was to be launched. The 48th marched via Frederick in Maryland and the 44th via Winchester in Virginia. The troops were far from ready for battle. The Virginian companies were issued with weapons when they arrived at Winchester.

Governor Sharpe of Maryland had advised a methodical advance establishing forts at intervals. Braddock urged by Orme ignored this advice other than building a rough fortification at Little Meadows in the early stages of the march.

The first leg of the march was of 20 miles to the Little Meadows above the eastern branch of the Youghiogheny River. Here the expedition, on the advice of George Washington who held the appointment of aide de camp to Braddock, was divided into two. Braddock took a force of 1,500 men with some supplies in what Washington hoped would be a rush to the French fort. However the pace was still too slow.

Braddock finally cleared the mountains after an 80 mile march and crossed the main branch of the Youghiogheny on 29th June 1755. The expedition was plagued by the shortage of supplies and by this time the troops were near to starvation, suffering from scurvy through living on salt beef provided by the Royal Navy. There was no forage and the draught horses were dying in numbers. Quantities of flour were damaged by heavy rain.

Progress was painfully slow as the army was required to cut a twelve foot wide road with bridges. On the worst day in the early part of the march it took 18 hours to cover 3 miles.

Water was a problem and the army suffered from endemic fevers. Washington was struck down and left at Bear Camp, catching the army up in time for the battle.

Defensive precautions during the march seem to have been good and there were few casualties to the hostile Indians.

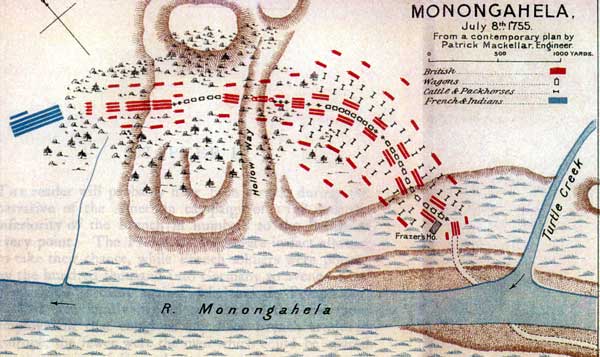

The final day’s march was on 9th July 1755. The route adopted required the army to ford the Monongahela, march along the east bank for 2 miles and then ford back for the final 7 mile approach to the French fort.

Both river crossings were expected to be contested. Although signs of Indian encampment were found there was no resistance to the crossings.

At around 1pm on Wednesday 9th July 1755 the army formed up around Frazier’s Cabin on the western bank of the Monogahela for the final 7 mile march to the fort. The troops set off apparently without the previous elaborate system of outlying pickets, as it was assumed there was to be no resistance and the fort would be found abandoned. All were in high spirits and the drummers played the Grenadier’s March.

They were wrong. A party of some 300 Indians and around 30 French colonial troops came down the path and attacked the advanced party of Lieutenant Colonel Gage and three companies of foot. Firing broke out and the Indians fanned out down the flanks of the army in a horse shoe attack.

Sir John Saint Clair, the deputy quartermaster general, commanding the working party, formed up his two companies of Virginians (Polson and Peronnee) and two 6 pounder cannon. The almost total lack of discipline and training in the British and American troops was fatal.

The main body of troops came up from the rear and collided with Gage’s retreating companies. The troops formed a mass into which the Indians fired.

It seems that most of the casualties in the British Force were inflicted through the troops shooting each other. The firing generated a heavy pall of gunpowder smoke that was hemmed in by the tree cover. After the battle many of the wounded were found to have wounds from British musket balls rather than the smaller calibre French issue.

Lt Col Gage attempted to take the high ground on the right flank, but he was wounded and his soldiers refused to advance further.

The army finally fled back across the river and continued back along its advance route until it reached Gist’s plantation on the far side of the Youghiogheny.

Braddock had been shot in the lung and helped from the field by Washington, Orme and other officers.

Captain Robert Orme painted in London by Sir Joshua Reynolds in the years after the Monongahela campaign. Orme found himself blamed for the failure and resigned from the army

Sir Peter Halkett was killed with his younger son. Also killed were: Captains Cholmley (48th), Tatton and Githius (44th), Shirley (Braddock’s secretary and son of the Massachusetts’ Governor), Polson and Spendelowe. 11 subalterns from the British Regiments and 4 from the Virginia Companies were killed.

It is claimed that the force did not begin the retreat for three to four hours. This seems unlikely. The British soldiers carried 24 rounds into battle. It seems likely that once these were expended the retreat began. It is unlikely that there was sufficient organisation for a resupply.

At the rear of the column the wagon drivers cut their teams free and fled. There was considerable carnage in the river but the Indians did not continue the pursuit beyond the river. Each company had two women permitted to march with it. A number of women and children were killed and scalped.

12 prisoners were stripped naked and dragged back to Fort Duquesne. A prisoner William Smith watched as the prisoners were tortured to death during the night at the river-side.

Casualties:

British and American: 26 officers killed, 37 wounded. 430 soldiers killed and 385 wounded.

French and Indians: probably less than 30 killed. Wounded unknown.

Follow-up:

The remnants of Braddock’s force now commanded by the dispirited and unenthusiastic Colonel Dunbar withdrew to Philadelphia and were later transferred to the North.

The defeat unleashed a wave of Indian attacks on Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania, many settlers being killed or abducted. Indian raids reached almost to Philadelphia. Defence of the three colonies was left to the local administration. The Royal Government had failed in its most important function- protection of its citizens- and would never have the same standing.

Heroes of the battle:

M. de Beaujeu who led the attack and was shot dead in the opening moments George Washington, present in spite of incapacitating illness, helped the dying Braddock and his wounded aides, Orme and Morris, from the field and rode 30 miles after the battle to bring help from Colonel Dunbar’s force. Washington had, before the march from Will’s Creek began, ridden to Williamsburg and back to obtain money for the soldiers pay.

The burial of Major General Edward Braddock after the battle on the Monongahela, shown in an idealised print. After the burial, waggons were driven across the site to ensure it could not be found by the French and Indians presumed to be pursuing the beaten army.

Anecdotes and Traditions:

- It is widely claimed that the battle was lost because the British troops were required to fight in formal European formation while the American troops used a more appropriate fighting order. There are clear references in the authorities to American soldiers fighting among the trees. It would seem that none of the formations in Braddock’s force were competent militarily. There was probably little difference in background between the soldiers of the British regiments and the colonial companies. Some of the recruits raised in Virginia and Maryland were escaped indentured servants brought from Britain.

Others were immigrants. Polson, Hogg, Stevens, Craik and other officers had reached America in the previous nine years. There is little in the fighting in 1753 and in 1754 at Fort Necessity to suggest that the Virginia Regiment was particularly competent at Indian fighting. The soldiers in the force who may have experienced Indian warfare were Captain Edward Bryce Dobson’s North Carolina rangers. There appears to be no indication that this company took part in the battle on 9th July 1755. - Edward Braddock was an unlikely appointment for commander in chief in America. He had served as a regimental officer in the Coldstream Guards until 1753, when he purchased the colonelcy of the 14th Regiment in Gibraltar, and had limited campaign experience. It seems that no more reputable general officer was prepared to accept the American appointment with the imminence of a European campaign.

- Tom Fossit of Shippensburg Pennsylvania a locally recruited soldier in the 48th claims to have shot Braddock. This seems to be discounted by the authorities.

- The failure of the British to engage the support of more Indians may be attributed to any of the following: the fear of the Ohio Indians of a colonist influx in the event of British success, Braddock’s lack of understanding of Indian ways, a British/Virginian view that Indian assistance was unnecessary.There were damaging conflicts within the army:

- 4 companies of the 44th under Sir Peter Halkett had been overwhelmed by the rebels in the Jacobite victory at Prestonpans in 1745. The 48th had been highly successful in the ’45, being one of the few regiments to stand their ground at Falkirk. There appears to have been considerable friction between the two regiments.

- Almost certainly a legacy of the ’45, Braddock and Orme treated the three Scots senior officers, Halkett, Dunbar and Saint Clair with contempt. Several of the Virginian officers may have been fugitives from the ’45: Polson, Craik, Stevens and Hogg. Polson was accused by British officers of being a Jacobite and demanded to be tried by court martial. Braddock had favourites: Orme, Lieutenant Colonel Burton, Capt Morris, Capt Dobson and George Washington whom he probably considered English. It was apparently Braddock’s plan to form the provincial companies into a royal regiment of foot of which Burton would have been appointed colonel, Major Sparke of the 48th, lieutenant colonel and Washington the major. Orme would have taken Burton’s lieutenant colonelcy of the 48th. The plan foundered with the defeat.

- The Virginian officers who had served in 1754 were still owed pay by the Commonwealth and were considered to be incompetent by the British.

A number of the participants in Braddock’s expedition to Fort Duquesne

went on to achieve fame or notoriety, among them:

- George Washington.

- Lt Colonel Gage became British Commander in Chief in America on the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War.

- Captain Horatio Gates became a major general in the American Continental Army and was in command at Saratoga.

- Captain Charles Lee of Halkett’s 44th became a major general in the Continental Army.

- James Craik became Washington’s surgeon.

- Captain William Mercer became a major general in the Continental Army.

- Lieutenant Hotham of Dunbar’s 48th commanded at Detroit in Pontiac’s war.

Captain Robert Orme had made himself so unpopular that the opportunity was seized to blame him for the disaster. He was compelled to leave the army within a year, but not before Sir Joshua Reynolds had painted one of his best known portraits of him. It hangs in the National Gallery in London.

General Braddock’s last words are reported to have been: “We shall know how to fight them next time.”

The Battle on the Monongahela: Major General Edward Braddock falls from his horse, mortally wounded

References:

- Ill-Starred General, Braddock of the Coldstream Guards by Lee McArdle.

- Braddock at the Monongahela by Paul E. Kopperman.

- Montcalm and Wolfe by Parkman.

- Military Affairs in North America by Stanley Pargellis (contains contemporary accounts of the campaign)

- History of Cumberland, Maryland by Lowdermilk (contains Washington’s copy of Braddock’s Order Book).

- History of an Expedition against Fort Du Quesne in 1755 by Winthrop Sargent (contains Orme’s subsequent report on the campaign and the Seaman’s Journal).

- Braddock’s Defeat edited by Charles Hamilton (contains the Diary of Captain Cholmley’s batman, the Diary of a British Officer and the 44th Order Book).

- History of the British Army by Fortescue.

- Writings of George Washington

- With Braddock’s Army: Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vol XXXII page 305. Diary of Charlotte Brown, the matron to the British military hospital.

Map of the Route of Braddock

Map of the route taken by Major General Edward Braddock’s Army in

Maryland and Pennsylvania during its advance to Fort DuQuesne 29th May

to 9th July 1755.

The previous battle in the British Battles sequence is the Battle of Plassey

The next battle in the British Battles sequence is Braddock’s Defeat Part I

To the French and Indian War index