The heavy defeat of the Pragmatic allies on 21st June 1747 that showed up the inadequacies of the Duke of Cumberland’s generalship

Marshal Maurice de Saxe and King Louis XV of France at the Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession

The previous battle of the War of the Austrian Succession is the Battle of Rocoux

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Prestonpans

To the War of the Austrian Succession index

Battle: Lauffeldt

War: War of the Austrian Succession or King George’s War.

Date of the Battle of Lauffeldt: 21st June 1747 (old style) (2nd July 1746: new style)

Marshal Maurice de Saxe commander of the French Army at the Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by David Morier

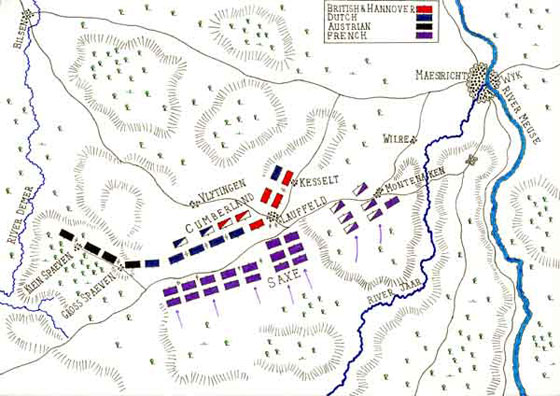

Place of the Battle of Lauffeldt: In the ground to the West of Maestricht between the Meuse and the Demer rivers in the Netherlands.

Combatants at the Battle of Lauffeldt: French against British, Hanoverians, Hessians, Austrians, Bavarians and Dutch.

Generals at the Battle of Lauffeldt: Marshal Maurice de Saxe commanded the French army, although King Louis XV of France was present.

The Duke of Cumberland was commander-in-chief of the Pragmatic army with Marshal Batthayani commanding the Austrian and Bavarian contingent and Prince Waldeck commanding the Dutch.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Lauffeldt: 120,000 French against 90,000 troops in the Pragmatic army.

Winner of the Battle of Lauffeldt: the French

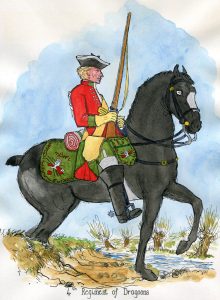

6th Dragoons: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Richard Simkin

British Regiments at the Battle of Lauffeldt: Lauffeldt is not a battle honour for British Regiments. The British regiments present at the battle were: the Royal Scots Greys (2nd), 4th, 6th, 7th and the Duke of Cumberland’s dragoons; 1st and 3rd Foot Guards, Howard’s Old Buffs (3rd), Barrel’s (4th), 13th, Howard’s (19th), Campbell’s Royal Scots Fusiliers (21st), Royal Welch Fusiliers (23rd), Sempill’s (25th), 32nd, 33rd, 36th, 37th and Conway’s (48th) Foot.

Background to the Battle of Lauffeldt:

(See the introduction in the War of the Austrian Succession index)

With the end of the Jacobite rebellion at the Battle of Culloden on 16th April 1746 and the suppression of the clans in the Highlands of Scotland, the British Government was able, in early 1747, to send a larger force of British troops to Flanders to take part in the fighting against the invading French army, to be followed by the Duke of Cumberland as its commander-in-chief.

The contingent, to be commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, together with Hanoverian and Hessian troops numbered 35,000. In addition, there would be Dutch and Austrian contingents bringing the total Pragmatic field army to around 130,000 men.

The Prince of Waldeck was elected to command the Dutch troops. Marshal Batthyani commanded the Austrians.

Duke of Cumberland’s Dragoons: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession

The French were entrenched in Brussels, Ghent and Louvain, towns of the Austrian Netherlands they had captured over the preceding winter, watched by some irregulars dispatched by the British officer General Ligonier. The French strength was 240 squadrons of horse and dragoons and 190 battalions of foot, some 160,000 men.

The Pragmatic allies marched out of quarters in late March 1747 with 146 squadrons of horse and dragoons and 101 battalions of foot.

Over the winter the British horse regiments had undergone the humiliation of being downgraded to dragoons as an economy measure (dragoons were paid significantly less than horse and were less well mounted). This involved discharging the existing personnel of each regiment and re-recruiting as dragoons. Hence no regiments of British horse/dragoon guards were available for service in Flanders in 1747.

The Pragmatic army formed up in the area of Roermond on the lower reaches of the River Meuse, where they were joined by the Duke of Cumberland, fresh from his success against the Jacobites and eager to give battle to the French.

The Duke of Cumberland’s status as younger son of the King of England, source of substantial subsidies for the Pragmatic field army, gave him a precarious authority over the other national contingents of which he was nominally the commander-in-chief. Even so the army’s deployment was a matter of compromise rather than command.

While initially the Duke of Cumberland’s intention was to recapture Antwerp from the French, the strength of the garrison deterred him and the Pragmatic army moved south-east to protect Maastricht on the River Meuse from Marshal Saxe and the army of Marshal Clermont.

General Daun, with 28 battalions, was under orders to attack Marshal Clermont’s troops at Tongres. Daun reached the area of a building called the ‘Commanderie’, which would form the right wing of the Pragmatic Army in the forthcoming battle.

British regiment of foot: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Richard Simkin

As Cumberland’s army approached Maastricht, Marshal Saxe moved to interpose his troops between the Pragmatic army and the River Meuse south of Maastricht. Marshal Saxe moved his army with considerable speed, covering some fifty miles in two days, while the Duke of Cumberland spent a day of inaction before advancing to the River Meuse.

King Louis XV accompanied the French army and was present at the battle, as he had been at the Battle of Fontenoy.

The opposing armies converged on the ground to the west of the River Meuse and to the south of Maastricht on 20th June 1747 (old style). While Marshal Saxe was fully informed of the whereabouts of the approaching Pragmatic army, the Duke of Cumberland and his commanders were not aware that the French army had interposed itself and was forming up on the high ground between them and the River Meuse.

Sir John Ligonier: Battle of Lauffeldt fought on 21st June 1747, in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Joshua Reynolds

General Ligonier, commanding a substantial force of the Pragmatic cavalry, was under orders to occupy the high ground running parallel to the River Meuse called the Heerderen, thereby blocking the road from Tongres to Maastricht which ran along the top.

Cumberland intended the Pragmatic army to encamp on the ground between the Heerderen and the River Meuse, blocking the way to Maastricht against Saxe’s French army.

As Ligonier came up he found the French cavalry were already holding the Heerderen, in significantly greater strength than his force. Ligonier halted in the village line short of the Heerderen, to await the arrival of the rest of the Pragmatic army and his commander the Duke of Cumberland.

The infantry columns of both the French and the Pragmatic army were still marching up. Ligonier provided a protective cover against a French attack.

As Cumberland’s army arrived on the battle field, they took up positions with the Austrians on the right flank (the position of honour Marshal Batthiyani had taken for his troops from the British in 1746, causing great indignation), occupying the Commanderie and the twin villages of Grosse and Kleine Spauwe. The Dutch occupied the ground between Gross Spauwe and Vlytingen and the British, Hanoverians and Hessian infantry occupied the key villages of Vlytingen and Lauffeldt.

Ligonier’s cavalry moved across to the left flank and took up position in front of the village of Kisselt.

The British Foot Guard regiments held Vlytingen while a force of 8 British and Hessian battalions occupied Lauffeldt.

Late on 20th June 1746 (old style) the two armies were in position, although there was considerable movement among the French regiments as Marshal Saxe prepared his army for the attack the next day.

Engagements took place between the two sides. Around the Commanderie French and Austrian hussars skirmished.

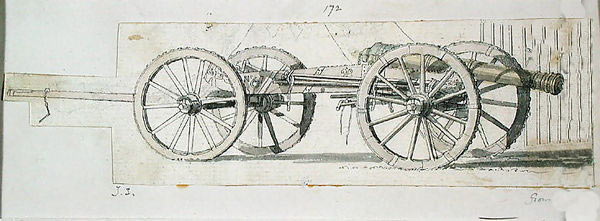

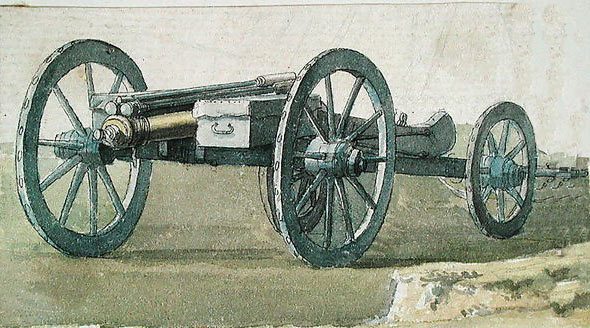

The British artillery established a battery of six 6 pounders outside Lauffeldt and there was a sharp exchange of cannon fire. A shell exploded in a French battery causing substantial casualties. The firing was ended during the evening by a heavy fall of rain.

British encampment at Maastricht in 1747: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Thomas Sandby war artist to the Duke of Cumberland

During the night, the smaller guns were distributed in twos among the infantry battalions and the heavy guns established in batteries in the defended villages.

An uncomfortable night was spent in the rain with no rations.

Account of the Battle of Lauffeldt

On 21st June 1746 (old style) the British guns opened fire at 5am with the French replying from 6am. The bombardments continued until 8.30am.

4th Dragoons: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Mackenzies after Representation of Cloathing

In the early hours of the morning Sir John Ligonier returned from a conference of the senior commanders, the Duke of Cumberland and the Austrian Marshal Bathyani to find the British Foot Guards withdrawing from the village of Vlytingen and forming line behind the village. This was on the Duke of Cumberland’s orders and acting on his directions the British Foot Guards had set fire to Vlytingen.

The British and Hessian battalions were also withdrawing from the neighbouring village of Lauffeldt.

It was the Duke of Cumberland’s view that his infantry should form line in the open behind the villages and not attempt to defend them. The order had been given the night before that the battalions were to spend the night in the villages and in the morning to withdraw. No attempt was made to fortify the two villages which were largely destroyed by fire.

Ligonier pointed out to the Duke of Cumberland that it was the experience of battles like Blenheim that a fortified village determinedly held was a very difficult place to storm and that the battalions of foot should be moved back into the villages as quickly as possible and set to fortifying what was left of the structures.

The Duke of Cumberland accepted this advice and the British and Hessian battalions were ordered back into Lauffeldt. The British Foot Guards remained in line with the foot behind the villages.

Unfortunately, the Pragmatic withdrawal from the two villages was observed by Marshal Saxe and the French infantry columns were already under way to launch their attack.

The British, Hanoverian and Hessian battalions were not fully back in Lauffeldt when the French attack came in.

In the meantime, the Duke of Cumberland, not expecting any immediate French move, returned to the Commanderie to take breakfast with Marshal Batthyani.

The French infantry that attacked the two villages were the brigades of Monaco, Segur, La Fere, Bourbon, Bettens, Monin, des Vaisseaux, the Irish, Tour-du-Pin, du Roi and d’Orleans,

The French attack on the two villages of Vlytingen and Lauffeldt was the central feature of the Battle of Lauffeldt. The column intended to attack Vlytingen and finding the village abandonned wheeled and joined the assault on Lauffeldt, taking the village in flank. The attack took some four hours with the French gaining a foothold three times and on each occasion being repelled.

In all Marshal Saxe sent in some 50 French infantry battalions against the 10 British, Hanoverian and Hessian battalions.

Howard’s 3rd Old Buffs: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Mackenzies after Representation of Cloathing

During the course of the fighting over Vlytingen and Lauffeldt 9 Austrian battalions were brought over from the right flank and put into the second line to release British and Hanoverian battalions to be hurried forward to join the garrison in Lauffeldt. Eventually the French were pushed back and the Duke of Cumberland ordered his infantry to advance. He also sent to Marshal Batthyani asking that the Austrians advance from their position on the right of the Pragmatic line and attack the French on the flank. Batthyani evaded the request and did not move.

It is at this point that the crisis of the battle occurred. James Wood of the Royal Artillery in his diary of the battle recorded: ‘..Advanced and fired at one another for three hours and a half, as fast as we could load. At 11.30am they at last retreated, we following with loud hurrahs, but the Dutch horse gave way and the Austrians never coming to back us, and a large body of both horse and foot coming from the right to the assistance of the French and as they say, the French King coming up along with them inspired them with new life and courage which caused them immediately to turn and advance on us most furiously; and they really behaved very well, though we cut them down with grapeshot from our batteries of 12 pounders yet they did not seem to mind it, but filled up their intervals that we made with grapeshot as they advanced. Being overpowered we were at last obliged to retreat something faster than we advanced….’

Sullivan in his History of the Irish Brigades in the service of France described the battle in some detail from the French perspective. Sullivan quotes a captured British officer as reporting that a Dutch cavalry regiment bolted and in its flight rode through two Pragmatic brigades dispersing them. He quotes another officer as recording that the Dutch rode through the Royal Scots Fusiliers and the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. The collapse of the Dutch cavalry regiment was widely blamed for the loss of the battle.

Laffeldt was finally taken by the French at midday. The Duke of Cumberland took the view that his army was defeated and ordered the infantry to disengage and march towards Maastricht.

Cavalry battle: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Jan van Huchtenburg

In the meantime, on the left flank, Sir John Ligonier launched his 60 squadrons of cavalry in a charge against the opposing force of 140 squadrons of French cavalry. Ligonier’s charge was successful and the French were forced back beyond the village of Wilre. Wilre was captured and five French cavalry standards taken.

33rd Foot: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Mackenzies after Representation of Cloathing

Sir John Ligonier was about to exploit his success when he received a message from the Duke of Cumberland saying that the French had taken Lauffeldt and that Ligonier was not to advance. Cumberland was extricating his infantry and beginning the march to his left in the direction of Maastricht.

Ligonier sent a message to Cumberland describing his successful cavalry attack. He received a further order directing him to repeat the charge.

This time Ligonier attacked with just the 4 British dragoon regiments, the Hessian cavalry regiments refusing to follow. The charge burst through the French cavalry but encountered a substantial body of unshaken French infantry.

Halted by the French infantry Ligonier’s British regiments were attacked by French cavalry reserves; the Regiments d’Anjou, Carabiniers, Royal and de Broglie. In the course of this melee Sir John Ligonier was captured by two French Carabiniers.

Covered by Ligonier’s two cavalry charges the Pragmatic army was able to disengage, march off to the left and reach Maastricht.

In the course of the precipitate retreat from the two villages the British were forced to abandon nine 3 pounder cannon and seven 6 pounder cannon. The Hanoverians lost six cannon.

The captured General Sir John Ligonier (left on foot) is brought before Marshal Maurice de Saxe and King Louis XV of France at the end of the Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by August Couder

Casualties at the Battle of Lauffeldt:

The casualties of the Pragmatic allies were around 6,000. Included in this number were some 2,000 taken prisoner. 16 guns were taken by the French.

The British lost 2,000 men. The Scots Greys lost 160 men, the 6th Dragoons lost 120 men and Cumberland’s dragoons lost 100.

French casualties are said to have been around 10,000.

Follow-up to the Battle of Lauffeldt:

The Duke of Cumberland withdrew the Pragmatic army to Maastricht. Marshal Saxe and the French army retreated to Tongres, his plan to take Maastricht thwarted by the escape of the Pragmatic army.

British 6 pounder cannon: Battle of Lauffeldt 21st June 1747 in the War of the Austrian Succession: picture by Thomas Sandby war artist to the Duke of Cumberland

Following the Battle of Lauffeldt, Sir John Ligonier, now a prisoner of the French, was introduced by Marshal Saxe to King Louis XV. The occasion is recorded in the picture by August Couder (see above). The French King treated Ligonier well, much to the irritation of the Scots and Irish officers in the French service, who were sure that King George II would not treat them so graciously if they were to become prisoners of the British.

King Louis sent Ligonier on parole to the Duke of Cumberland with a message that he wished, if possible, to bring the war to a close. This did not happen until 1748 when the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle brought hositilities between Britain and France to a close with a general settlement.

Sir John Ligonier was exchanged by the French a few weeks after the battle and returned to his duties.

The Battle of Lauffeldt was considered a major victory for the Bourbon Monarchy of France. The Monarchy’s next important battle was the Battle of Rossbach against the Prussians on 5th November 1757.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Lauffeldt:

- The rate of fire during the Battle of Lauffeldt was very intense. Evan Charteris, in his book, recorded that in some of the British regiments the soldiers expended up to 100 rounds of ammunition (the standard battle issue was 24 rounds). Some of the cannon fired as many as 120 shots during the battle.

- The Duke of Cumberland and Marshal Saxe came close to being captured during the battle. Sullivan reports that the Duke, being short-sighted, mistook some Irish troops in scarlet coats for British. He realised his mistake just in time. Colonel Yorke, the Duke’s ADC, reported that the Duke was surrounded by a squadron of French cavalry. A French trooper laid hold of the Duke who struck him hard with his sword and escaped with the assistance of his staff. Marshal Saxe came close to being captured by the Scots Greys.

- It is considered that Lauffeldt showed the Duke of Cumberland in his true colours as a general. He failed to grasp that the line of villages once fortified would have provided a powerful position. At the crisis of the battle he lost his nerve and ordered the infantry withdrawal that Ligonier attempted to retrieve with his cavalry attack. It is said that Cumberland was bitterly jealous of Ligonier’s courage and decisiveness in the battle. He is said to have resented the casualties inflicted on his regiment of dragoons in Ligonier’s charge.

- After the capture of Sir John Ligonier, his ADC Lord Henry Campbell searched the battlefield for his general. Campbell was killed by marauding French soldiers. Ligonier’s other ADC William Keppell was captured in the charge.

- James Wolfe, the victor of the Battle of Quebec in North America on 13th September 1759, was a brigade major at the Battle of Lauffeldt and was wounded.

- General Rex Whitworth wrote biographies of Sir John Ligonier and the Duke of Cumberland. In the book on Ligonier published, in 1958, Whitworth described how Cumberland caused his infantry to withdraw from Vlytingen and Lauffeldt only to order them back into the villages on the advice of Ligonier, but with no opportunity to fortify them. Whitworth drew on the account given by Townshend, who was present at the Battle of Lauffeldt, for this aspect of the battle. In ‘Duke of Cumberland’, published in 1992, Whitworth made no mention of the withdrawal, nor did he repeat the assertions made in his ‘Ligonier’ book that Cumberland did not treat Ligonier with the same cordiality and affection after the Battle of Lauffeldt as he had before. It is clear that Ligonier by his gallant and timely cavalry charge on the army’s flank was widely considered at the time to have saved the army from wholesale capture by the French and to have rescued Cumberland from military eclipse. Horace Walpole stated in his ‘Memoirs of George II’ that Ligonier ‘performed an action of most desperate gallantry, which prevented the total destruction of our troops, and almost made Marshal Saxe doubt of his victory.’

- The picture of the Duke of Cumberland at the Battle of Lauffeldt (see above) gives the Duke prominence with Lord Henry Campbell. Sir John Ligonier occupies a modest position in the composition facing away from the artist. This picture hangs in Inverary Castle, the seat of the Duke of Argyll, whose relation Lord Henry was. The emphasis or lack of emphasis for Ligonier was perhaps tactful at a time when the Duke of Cumberland held an all-powerful position in the British military establishment and reflected the jealousy of Ligonier that the Battle of Lauffeldt generated in the Duke of Cumberland.

References for the Battle of Lauffeldt:

- William Augustus Duke of Cumberland by Evan Charteris

- Field Marshall Lord Ligonier by Rex Whitworth

- Fortescue’s History of the British Army Volume II

- Fontenoy by Francis Henry Skrine

- Gunner at Large, diary of James Wood RA 1746-1765 edited by Rex Whitworth

- William Augustus Duke of Cumberland by Rex Whitworth

- Marshal of France: The life and times of Maurice de Saxe by Jon Mancip White

The previous battle of the War of the Austrian Succession is the Battle of Rocoux

The next battle in the British Battles series is the Battle of Prestonpans

To the War of the Austrian Succession index