The Royal Navy’s spectacular retribution on 8th December 1914 in the First World War, for the sinking of Admiral Cradock’s two ships, HMS Good Hope and Monmouth at the Battle of Coronel, with the destruction of Admiral Graf von Spee’s protected cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and light cruisers, Leipzig and Nürnberg

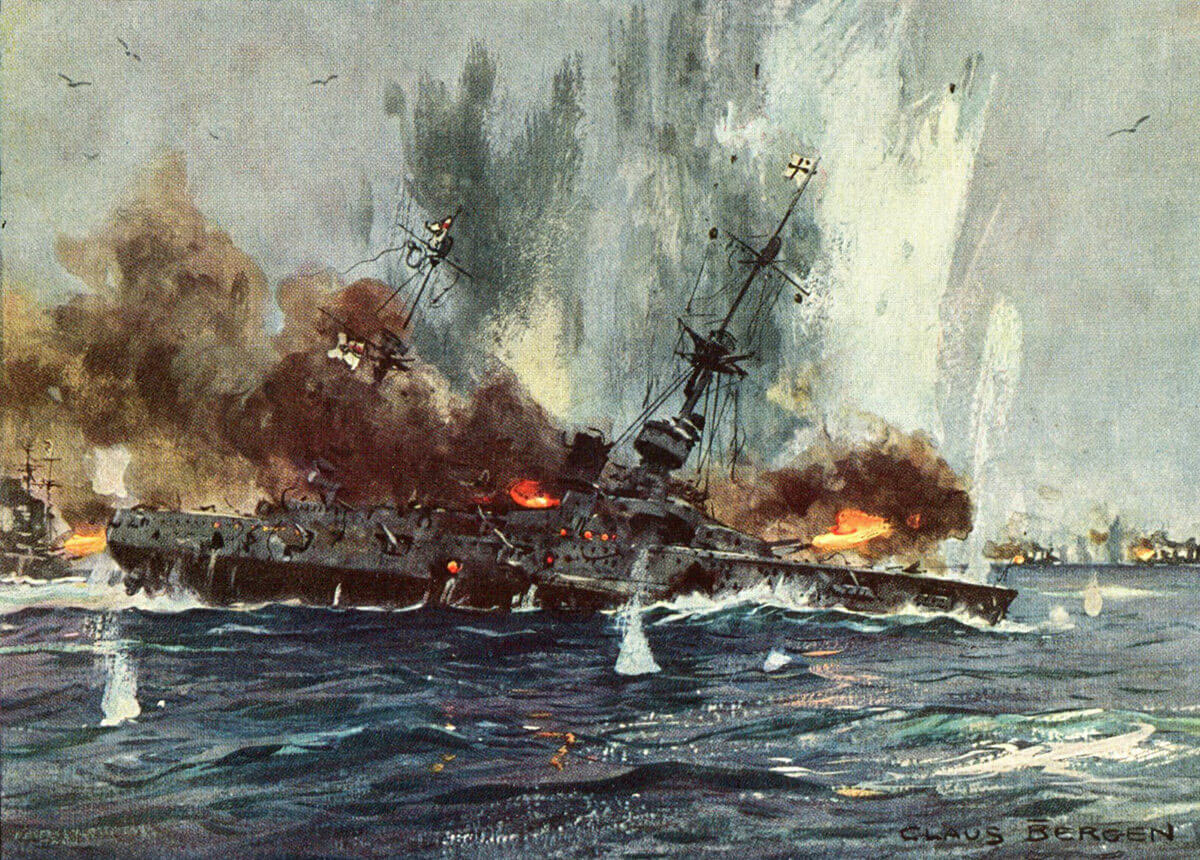

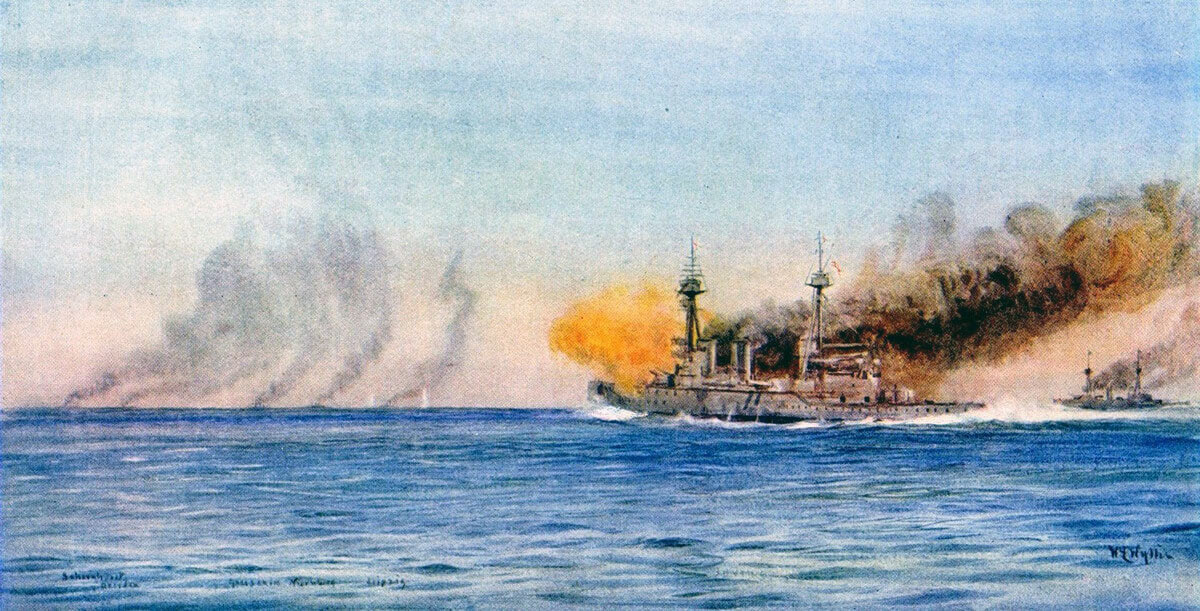

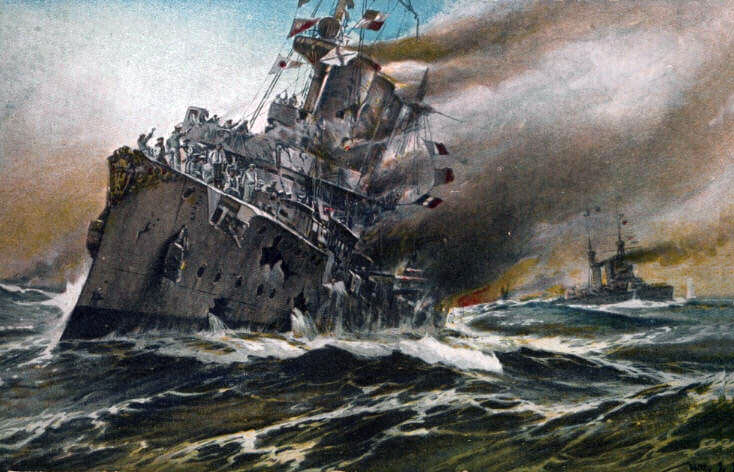

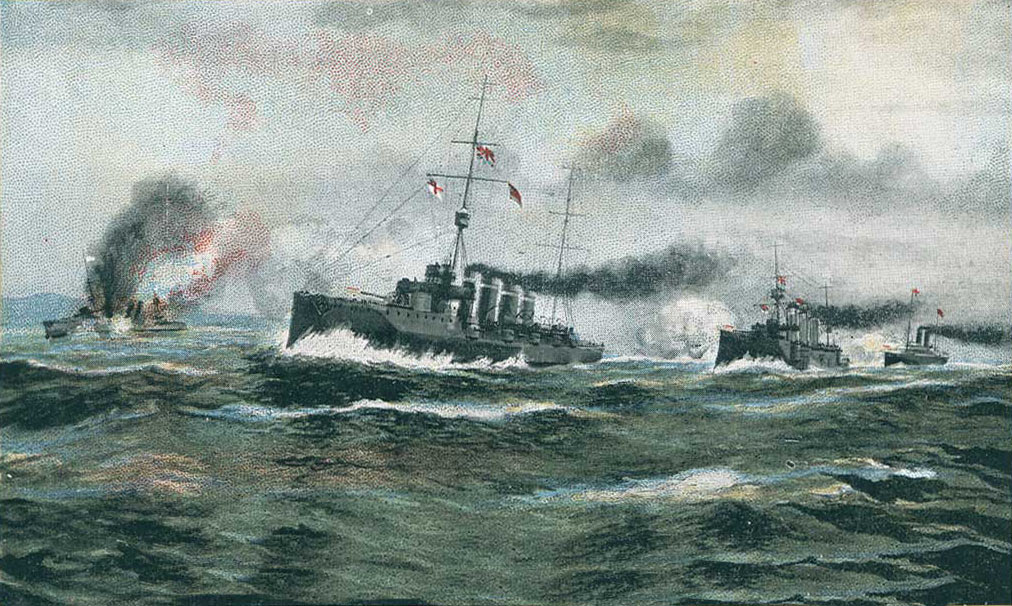

German Armoured Cruiser SMS Scharnhorst sinking at the Battle of the Falkland Islands 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Claus Bergen

Vice Admiral Reichsgraf Maximilian von Spee, the German admiral at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Coronel

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of the Dogger Bank

Battle: Falkland Islands

Date of the Battle of the Falkland Islands: 8th December 1914

Place of the Battle of the Falkland Islands: Off the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic

War: The First World War also known as ‘The Great War’.

Contestants at the Battle of the Falkland Islands: A British Royal Navy squadron against a German Imperial Navy squadron.

Admirals at the Battle of the Falkland Islands: The British Royal Navy Squadron was commanded by Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee. The German squadron was commanded by Vice Admiral Reichsgraf Maximilian von Spee.

Ships involved in the Battle of the Falkland Islands:

The Royal Navy:

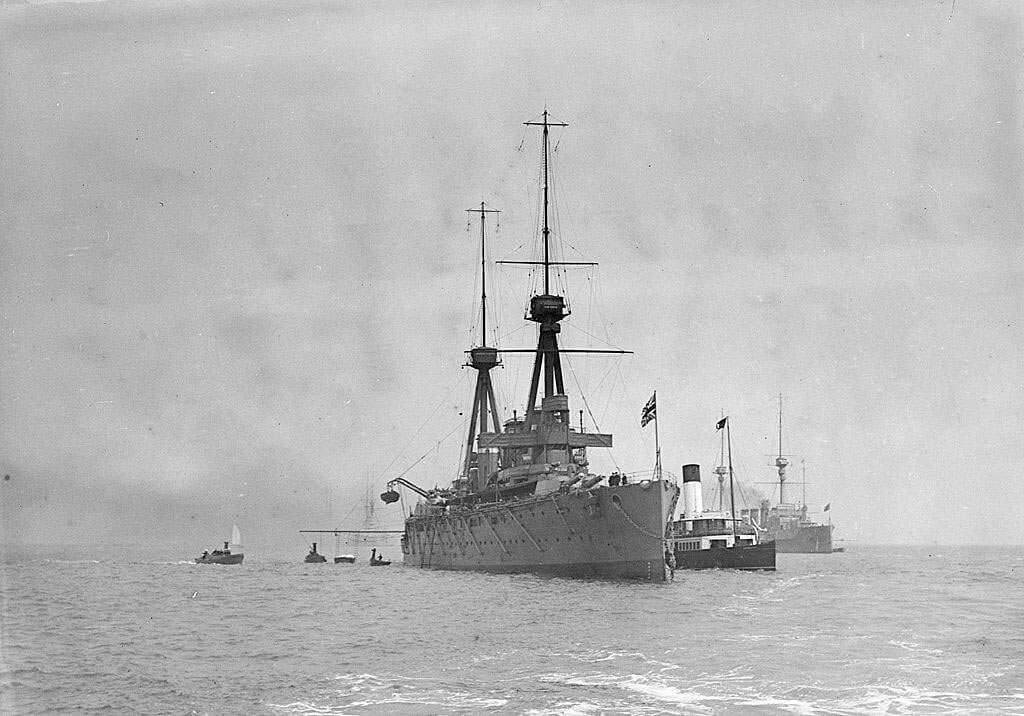

HMS Invincible: Battle Cruiser – completed in 1908 – 17,250 tons – armament 8 X 12 inch and 16 X 4 inch guns – maximum speed 28.6 knots – crew: Captain Beamish and 1,031 all ranks.

HMS Inflexible: Battle Cruiser – completed in 1908 – 17,250 tons – armament 8 X 12 inch and 16 X 4 inch guns – maximum speed 28.4 knots – crew: c. Captain Phillimore and 1,000 all ranks.

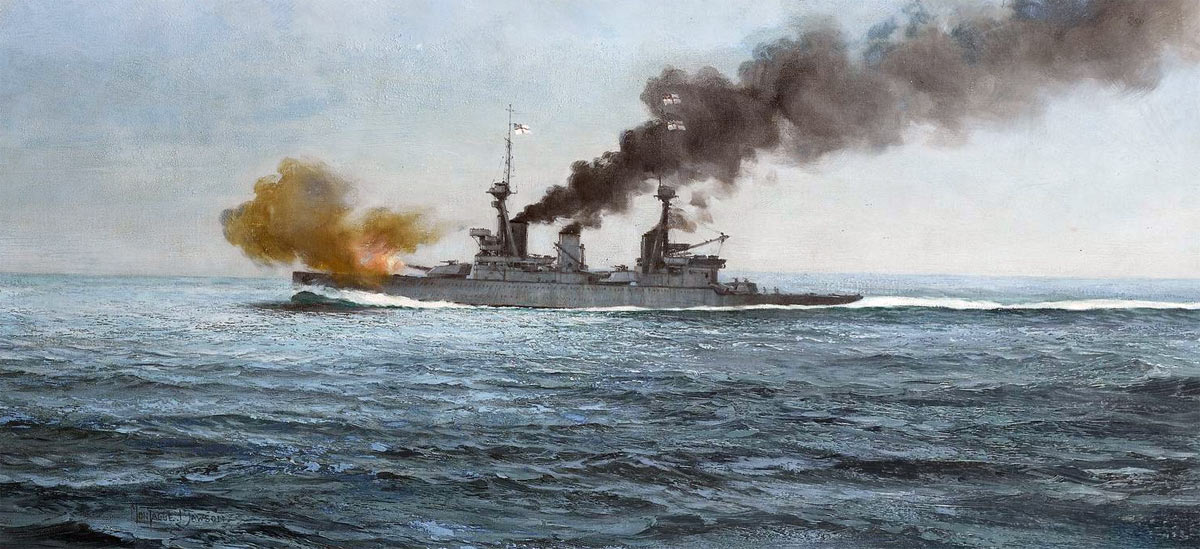

HMS Inflexible, the second British battle cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Montague Dawson

>HMS Kent: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser – completed in 1901 – 9,800 tons – main armament 14 X 6 inch guns – maximum speed 22 knots – crew: Captain Allen and 678 all ranks.

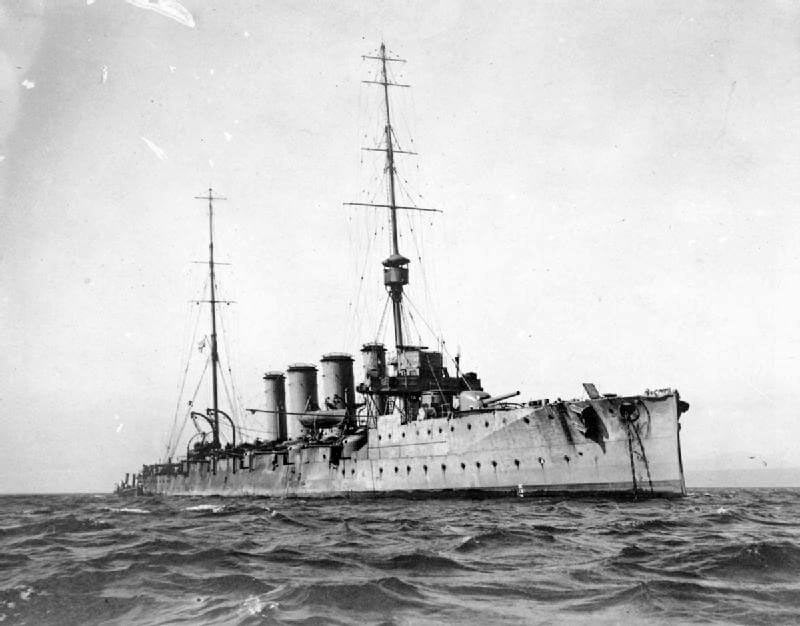

HMS Kent, British light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

HMS Cornwall: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser – completed in 1903 – 9,800 tons – main armament 4 X 6 inch guns – maximum speed 24 knots – crew: Captain Ellerton and 677 all ranks.

HMS Cornwall, British light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

HMS Carnarvon: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser – completed in 1903 – 9,800 tons – main armament 4 X 7.5 inch and 6 X 6 inch guns – maximum speed 22.1 knots – crew: Captain Skipworth and 609 all ranks.

HMS Carnarvon, British light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

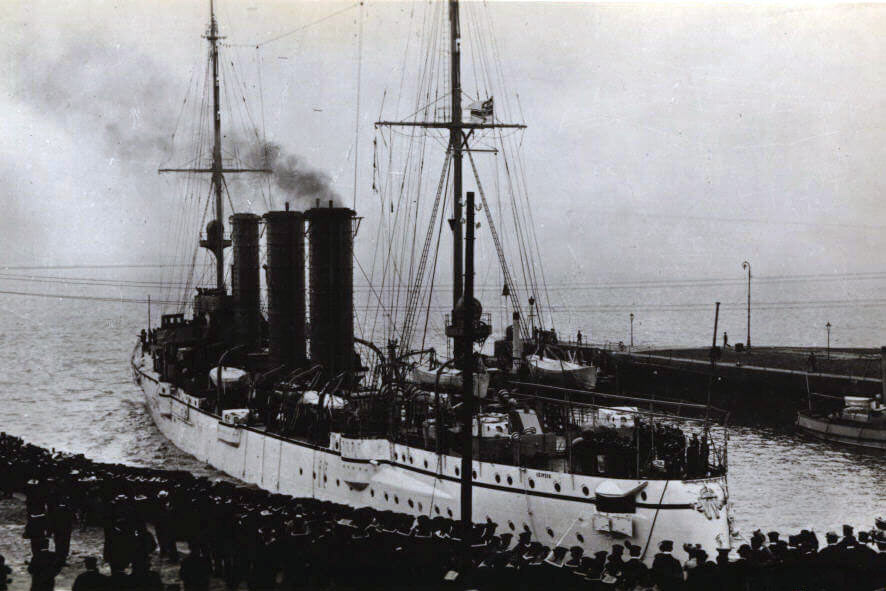

HMS Glasgow: Light Cruiser – completed in 1911 – 4,800 tons – main armament 2 X 6 inch and 10 X 4 inch guns – maximum speed 25.8 knots – crew: Captain Luce and 410 all ranks.

HMS Glasgow, British light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

HMS Bristol: Light Cruiser – completed in 1911 – 4,800 tons – main armament 2 X 6 inch and 10 X 4 inch guns – maximum speed 26.8 knots – crew: Captain Fanshawe and 410 all ranks.

HMS Bristol, British light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

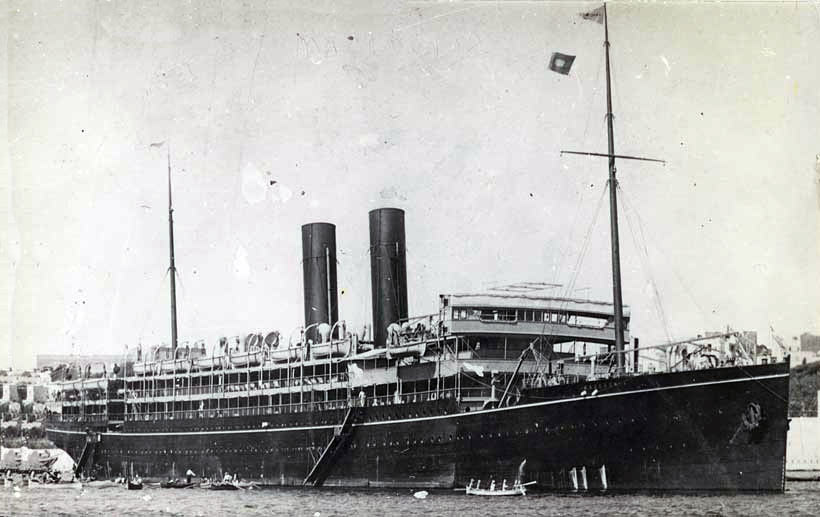

HMS Macedonia: auxiliary cruiser (ex – civilian ship) – 12,100 tons – main armament 8 X 4.7 inch guns: maximum speed 18 knots – crew: Captain Evans and 370 all ranks(crew as a merchant ship).

Macedonia as a civilian liner. Macedonia was a British auxiliary cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

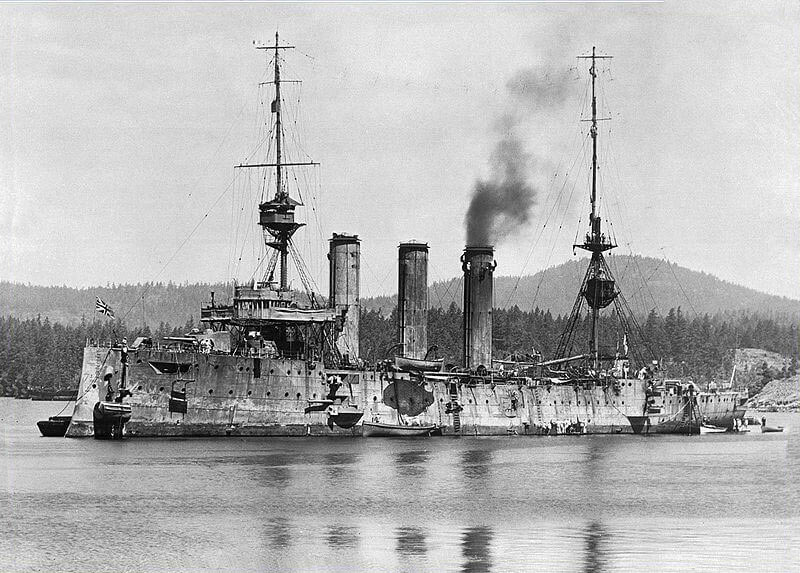

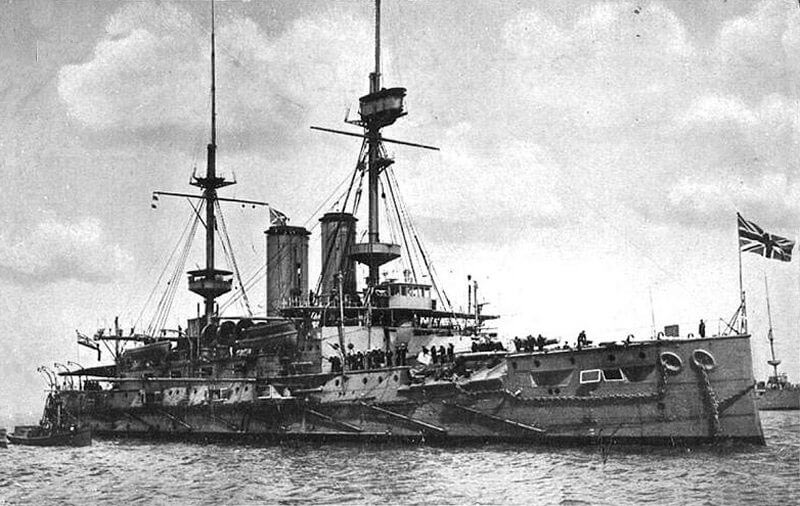

HMS Canopus: obsolescent Battleship – completed in 1897 – 12,950 tons – main armament 4 X 12 inch and 12 X 6 inch guns – maximum speed 16.5 knots. Captain Grant and 750 all ranks.

HMS Canopus, British battleship beached in Port Stanley during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

The German Imperial Navy:

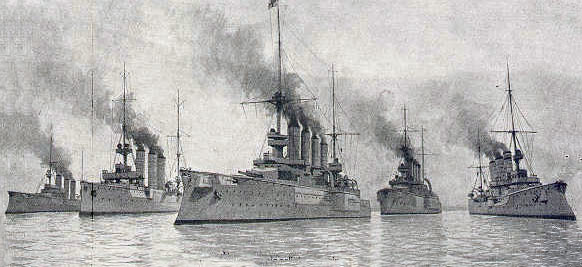

Admiral Graf von Spee’s squadron at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: SMS Nürnberg, Dresden, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Leipzig

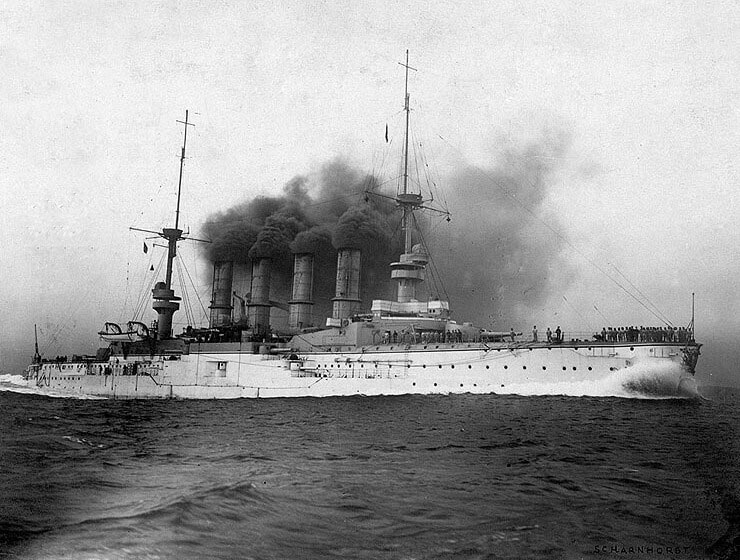

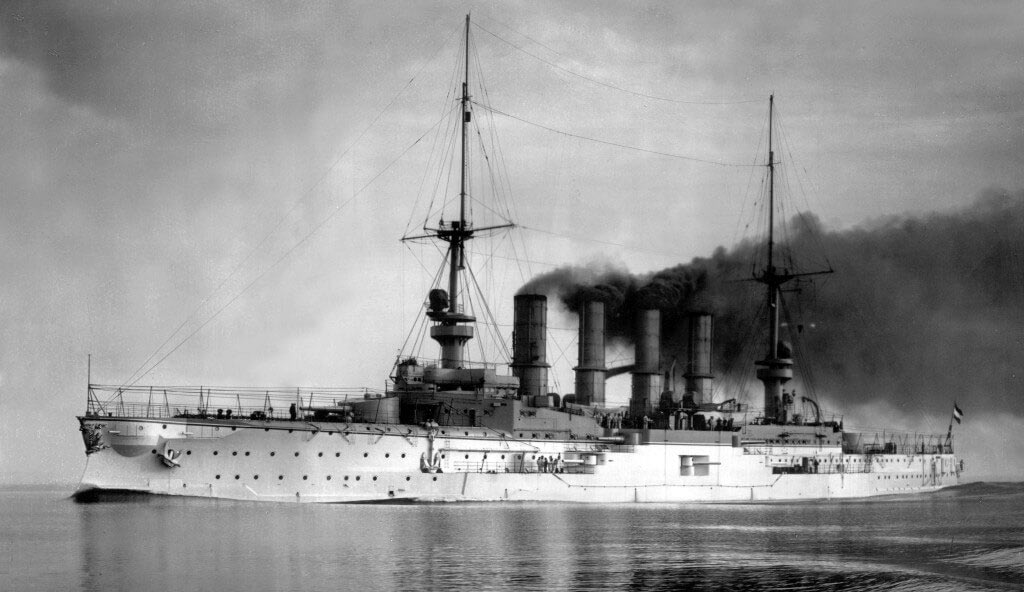

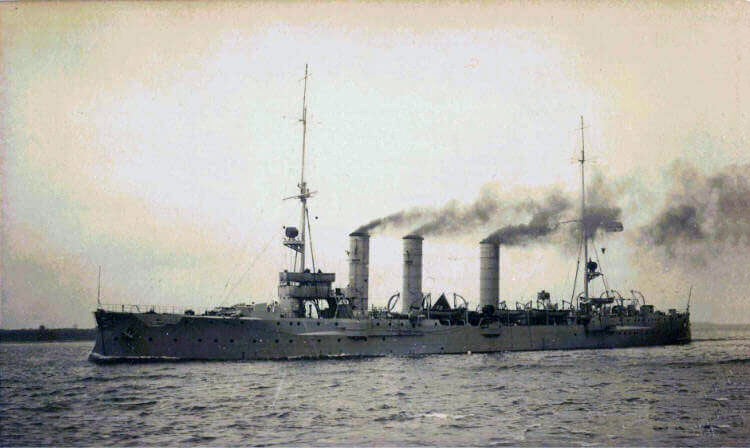

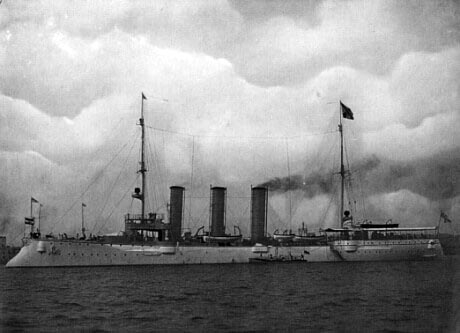

SMS Scharnhorst: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser – completed in 1907 – 11,600 tons – main armament 8 X 8.2 inch and 6 X 6 inch guns – maximum speed 21 knots – crew: 52 officers and 788 non-commissioned ranks (including the admiral’s staff).

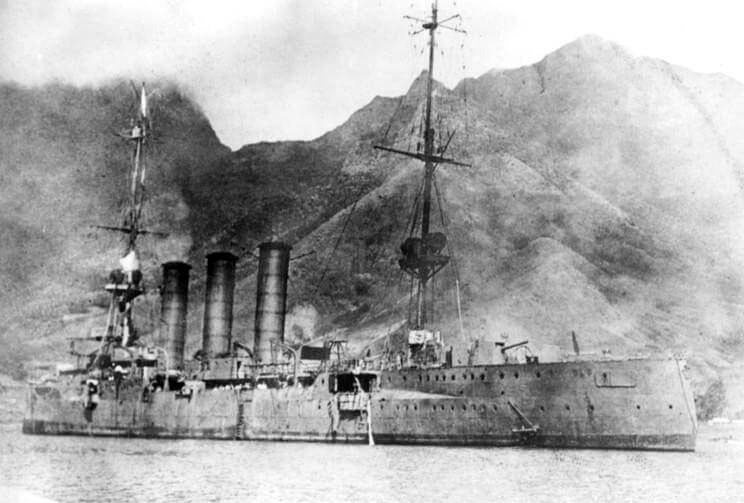

SMS Scharnhorst, the German flagship at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

SMS Gneisenau: Armoured (Heavy) Cruiser – completed in 1907 – 11,600 tons – main armament 8 X 8.2 inch and 6 X 6 inch guns – maximum speed 24.8 knots – crew: 38 officers and 726 non-commissioned ranks.

SMS Gneisenau, the second German armoured cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

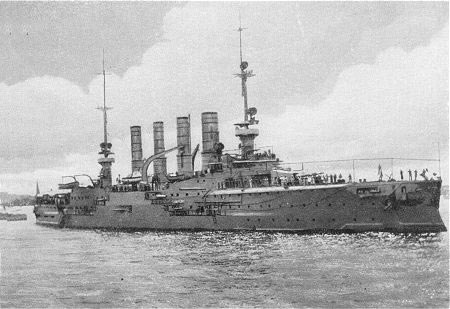

SMS Dresden: Light Cruiser – completed in 1909 – 3,600 tons – main armament 10 X 4.1 inch guns – maximum speed 24 knots (this was the theoretical maximum, but Dresden seems to have been able to reach 27 knots) – crew: Kapitän zur See Lüdecke 18 officers and 343 non-commissioned ranks.

SMS Dresden, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

SMS Nürnberg: Light Cruiser – completed in 1908 – 3,600 tons – main armament 10 X 4.1 inch guns – maximum speed 22.5 knots – crew: 14 officers and 308 non-commissioned ranks.

SMS Nürnberg, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

SMS Leipzig: Light Cruiser – completed in 1906 – 3,250 tons – main armament 10 X 4.1 inch guns – maximum speed 24 knots – crew: 14 officers and 280 non-commissioned ranks.

SMS Leipzig, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

All the above ships except Macedonia carried smaller guns, machine guns and torpedo tubes.

Seydlitz: hospital ship

Baden and Santa Isabel: colliers

Winner of the Battle of the Falkland Islands: The British squadron sank all the German ships other than the light cruiser Dresden and the hospital ship Seydlitz, which escaped. Dresden was tracked down by British cruisers Glasgow and Kent at the Chilean island of Mas-a-fuera and attacked on 14th March 1915. The Dresden’s captain scuttled his ship and the crew were interned.

Background to the Battle of the Falkland Islands:

The British admiralty heard of the destruction of Admiral Cradock’s squadron by the German squadron commanded by Admiral Graf von Spee at the Battle of Coronel on 1st November 1914 from a communiqué issued by the German Imperial Navy. Initially the news was discounted, as it made no mention of the battleship HMS Canopus, the ship that was intended to give Cradock a significant advantage in firepower over von Spee’s squadron.

Finally convinced by other reports of the loss of Cradock’s ships, the Admiralty faced a major crisis. Canopus and Cradock’s surviving light cruiser Glasgow were hurrying back towards the Falkland Islands, leaving no obstacle to von Spee escaping into the South Atlantic, where he could disrupt any of the important allied operations around the African coast.

Sir Julian Corbett in his Naval Operations states that the consequences of Coronel were felt in every naval theatre around the globe.

Rear Admiral Stoddart, British second in command at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

The Admiralty ordered Admiral Stoddart to concentrate at Monte Video his armoured cruisers HMS Carnarvon and Cornwall and the armoured cruiser HMS Defence, on her way from the Mediterranean to join Cradock. Canopus, Glasgow and Otranto, returning from the Coronel battle, were ordered to join Stoddart, as was the armoured cruiser HMS Kent from the East Atlantic.

A force of British, Japanese and Canadian ships was ready to deal with von Spee if he went north to the Canadian shore.

It was expected that, following his spectacular success at Coronel, von Spee would sail around the Horn and capture the Falkland Islands, temporarily defenceless.

Admiral Jellicoe, commanding the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, was ordered to detach the battle cruisers HMS Invincible and Inflexible from his 2nd Battle Cruiser Squadron for service in the South Atlantic.

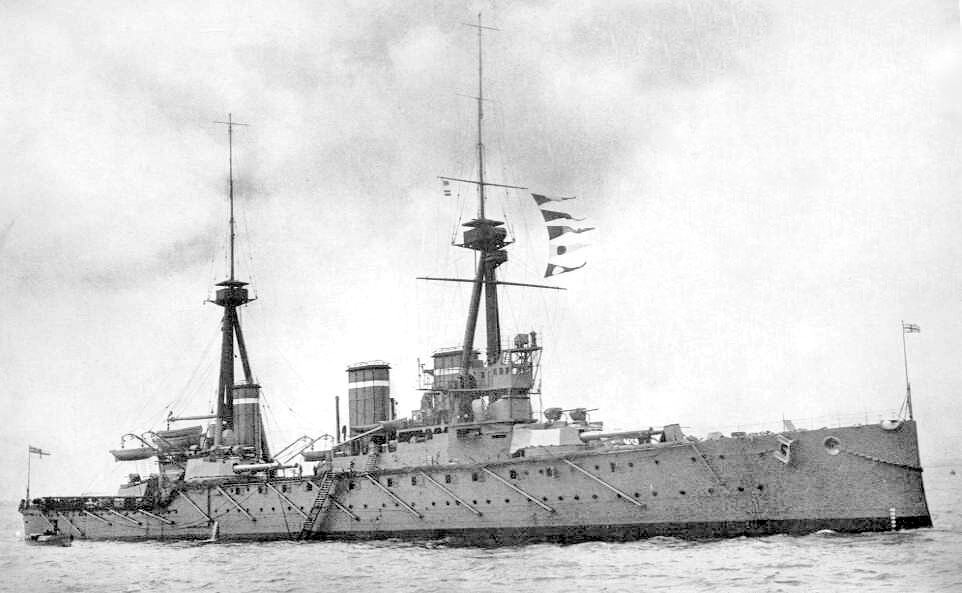

HMS Invincible, the British flagship at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914, at Spithead in 1910

Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee, the Chief of War Staff at the Admiralty, took over command of these two powerful and fast battle cruisers, with the appointment of Commander – in – Chief in the South Atlantic and Pacific. In addition, if his duties took him to any part of the North Atlantic or the Caribbean, that area would come under his command. This was an unprecedented appointment and reflected the seriousness of the crisis.

HMS Invincible and Inflexible:

Invincible was the lead ship of Britain’s three oldest battle cruisers. Equipped with 8 X 12 inch guns the ‘Invincibles’ were provided with no secondary armament, a controversial move. Due to continuing difficulty with her electrically driven turrets, Invincible was taken out of commission in early 1914 for a refit. The refit was not complete when the Royal Navy mobilised on 1st August 1914 and did not finish until 12th August. Invincible was re-commissioned on 2nd August 1914 with a new crew comprising RN, RNR and RNVR officers and non-commissioned ranks. Invincible was present at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August.

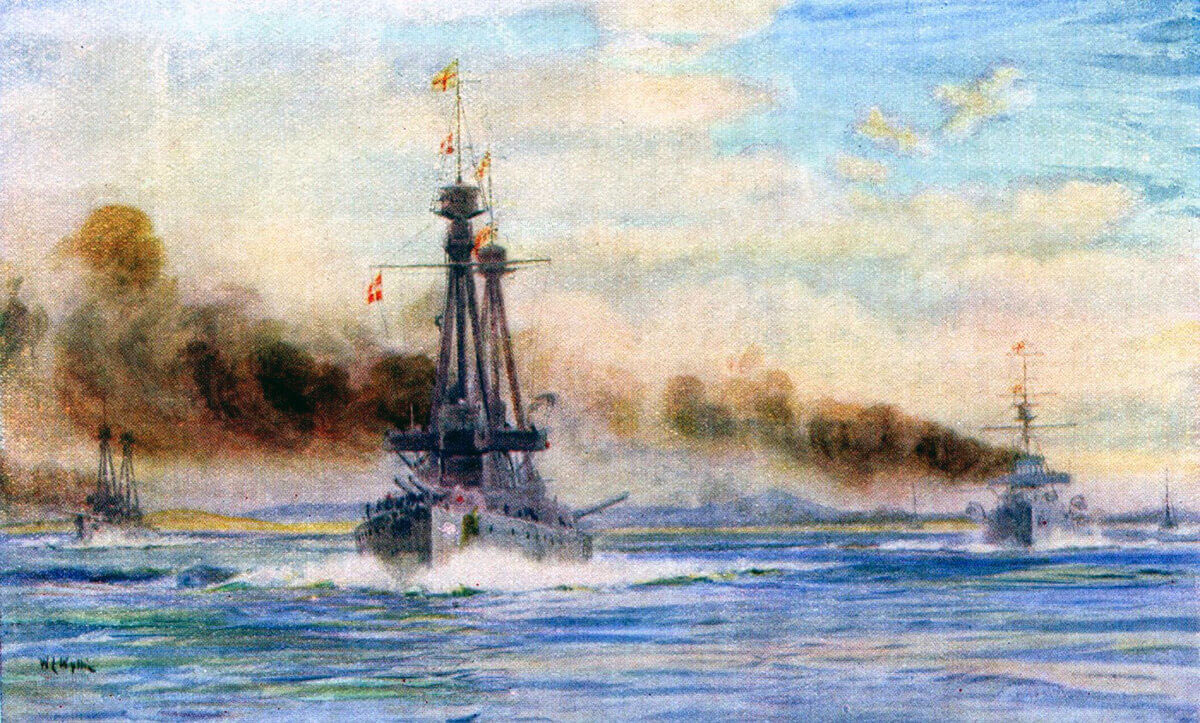

HMS Invincible and Inflexible leaving Stanley Harbour at the beginning of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

On the outbreak of the Great War, Inflexible was the flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet. She saw action in the pursuit of the German cruisers Goeben and Breslau before returning to Britain on 15th August 1914. She remained crewed substantially by Royal Navy personnel.

Admiral von Spee’s squadron comprised ships stationed in the Pacific for a number of years before the war broke out. Their crews were almost entirely regular German naval personnel. Spee’s two armoured cruisers, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, were particularly efficient ships, each having won shooting awards several times. Von Spee’s ships had been at sea for several months under active service conditions and were all in need of refit.

At midnight on 5th November 1914 HMS Invincible and Inflexible left Cromarty on the north-east coast of Scotland for Devonport, Plymouth, which they reached on 8th November. In spite of a need for repairs to Invincible the two battle cruisers sailed for the South Atlantic on 11th November 1914.

Sturdee was ordered to sail to the Cape Verde islands, off the west coast of Africa, and then to the Abrolhos Rocks rendezvous off the coast of Brazil, where he would meet Stoddart’s ships. On the way Sturdee was to collect the cruiser HMS Bristol and the auxiliary cruiser Macedonia, to strengthen the light cruiser element of his squadron.

On 8th November 1914 the surviving ships from Cradock’s squadron, HMS Canopus and Glasgow with the colliers, arrived in the Falkland Islands and refuelled, while Otranto went straight to join Stoddart, the other ships following on.

On 12th November 1914 a further battle cruiser HMS Princess Royal was detached from the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow to join Admiral Hornby, watching the German civilian ships in New York harbour, any one of which, it was feared, was designated an auxiliary naval cruiser.

Information to the Admiralty now suggested, correctly, that von Spee’s squadron was at Mas-a-fuera, an island off the Chilean coast and not, as feared, heading for the South Atlantic.

Instead of hunting von Spee’s ships in the Atlantic it now appeared that Sturdee would have to take his ships into the South Pacific and seek him there. Canopus was ordered to return to the Falklands and prepare to defend the harbour.

On 11th October 1914 HMS Glasgow joined Admiral Stoddart’s squadron which then moved northwards towards the Abrolhos Rocks rendezvous.

Stoddart did not hear of the despatch of HMS Inflexible and Invincible under Admiral Sturdee to the South Atlantic until 11th November 1914, the day he reached the Abrolhos Rocks. He there had three armoured cruisers, HMS Edinburgh Castle, Kent and Defence. HMS Bristol and Macedonia were searching for SMS Karlsruhe and HMS Glasgow was at Rio de Janeiro for repairs to her damage from the Coronel battle.

Admiral von Spee’s movements:

After the Battle of Coronel von Spee called at Valparaiso and, after the permitted 24 hour stay in a neutral port, sailed for the island of Mas-a-fuera off the Chilean coast, appointed as the rendezvous for the rest of his squadron.

SMS Scharnhorst, the German flagship at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Von Spee reached Mas-a-fuera to find the light cruiser SMS Leipzig already there with the colliers Amasis and Santa Isabel and a captured vessel. Baden arrived the next day with a further prize. The prizes were carrying coal which von Spee appropriated for his warships.

Admiral von Spee’s squadron leaving Valparaiso on 3rd November 1914: Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

On 8th November the cruisers Prinz Eitel Friedrich and SMS Dresden arrived with another prize also carrying coal.

Von Spee spent a considerable time assimilating these cargos of coal into his ships. He seems to have delayed his departure further in view of reports of German battle cruisers breaking out of the North Sea to join him (SMS Seydlitz, Moltke and possibly Von der Tann). The breakout did not take place.

On 15th November von Spee sailed south to the Straits of Magellan at the southern tip of South America, meeting the Leipzig and Dresden on the way with a further captured collier.

On 21st November 1914 von Spee reached St Quentin bay, on the Chilean coast some 500 miles short of Cape Horn, where he met three large German ships carrying coal and provisions. One of these, the Luxor, had evaded the Chilean authorities in leaving Coronel. Information on these ships reached the British admiralty and confirmed that von Spee was moving south to round Cape Horn into the South Atlantic. Von Spee’s delay would give Sturdee time to be ready to receive him.

Admiral von Spee’s squadron in line ahead off Chile in late November 1914: SMS Scharnhorst (the most distant ship), SMS Gneisenau, SMS Leipzig, SMS Nürnberg and SMS Dresden (in the foreground): Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Now that von Spee’s intention was clear the British Admiralty made some re-arrangements in ship deployments. This involved the return of capital ships from Africa to the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow and the posting of HMS Defence to Africa, once Sturdee’s battle cruisers were off the coast of Brazil.

Sturdee was ordered on arrival off the Brazilian coast to steam south with Stoddart’s and his own squadrons and round the Cape into the South Pacific. This order seems to be inconsistent with the Admiralty’s belief that von Spee was about to enter the Atlantic.

Sturdee received his orders when he arrived at Abrolhos Rocks and joined Stoddart on 26th November 1914. HMS Defence handed to Invincible her Poulsen Wireless gear which enabled radio contact to be maintained with London, via a similar equipped ship, Vindictive at Ascension Island, overcoming the handicap suffered in attempting to communicate with Cradock before Coronel.

Sturdee sent the three fastest colliers on to the Falkland Islands, while he coaled his ships and made his way south with the other colliers.

On the day Sturdee reached Abrolhos, 26th November 1914, von Spee left St Quentin Bay and headed south with Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Dresden, Leipzig and Nürnberg, the hospital ship Seydlitz and the two colliers, Baden and Santa Isabel. Prinz Eitel Friedrich was detached to raid on her own in the Pacific.

On 25th November HMS Canopus in the Falkland Islands received information from a passing ship that von Spee had rounded Cape Horn on 25th November, but she was unable to pass this information to Sturdee.

HMS Canopus in Port Stanley: Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

A number of misleading reports caused Sturdee to search the coast of Brazil, until HMS Bristol rejoined with information from the British Embassy in Rio de Janeiro that Sturdee had been misled. Abandoning the search Sturdee headed south with his squadron. On 3rd December 1914 Macedonia joined the squadron from Sierra Leone as it coaled in the River Plate.

On 4th December Sturdee received a message from the British Consul-General in Valparaiso that the Prinz Eitel Friedrich had been sighted off the port that morning. Sturdee’s conclusion was that von Spee’s whole squadron must be in the same place. Sturdee continued south with the intention of rounding Cape Horn and pursuing von Spee into the Pacific.

Von Spee in fact rounded the Horn on the night of 1st/2nd December 1914. He there captured a British four-masted barque, the Drummuir, loaded with anthracite coal for San Francisco. Von Spee took the Drummuir to Picton Island at the eastern end of the Beagle Channel, just north of Cape Horn, and spent three days unloading the anthracite into his ships, before sinking the Drummuir. He resumed his journey to the Falkland Islands on 6th December 1914.

Crew of HMS Kent on deck before the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Without the delay in unloading Drummuir von Spee’s squadron would have arrived in the Falkland Islands on 4th December. According to a German survivor a Dutch ship passing Picton Island informed von Spee that there was a British squadron in Port Stanley coaling. Von Spee calculated that the squadron must comprise the battleship Canopus, Carnarvon with, possibly, Defence, Cornwall and Glasgow. It seems that von Spee intended to lure these ships out to sea and sink them before wrecking the facilities at Port Stanley including the radio station and coaling facilities.

If von Spee was given this information it is surprising that he carried on with the plan to attack the Falkland Islands. He must have known that Canopus carried 12 inch guns which, although old, would outrange his own guns and could at the least inflict severe damage on his ships.

In fact the only British warship in the Falklands when von Spee rounded Cape Horn was HMS Canopus. Since its arrival on 12th November 1914 Canopus’ commander Captain Grant had been preparing defences for the islands. Canopus was lodged on the mud at the entrance to the inner harbour to ensure a firm gun platform, the harbour entrance had been mined and three shore batteries put in place with an observation tower to control their fire. Considerably delayed by the appalling weather, the work was completed on 4th December 1914.

Account of the Battle of the Falklands Islands:

The Falkland Islands and the crew of HMS Canopus were expecting their first visitors to be the German squadron. Unexpectedly on Monday 7th December the first arrivals were Admiral Sturdee’s ships.

All Sturdee’s ships anchored in the outer harbour, Port William, except for Bristol and Glasgow which went into the inner harbour, Port Stanley. Macedonia received the duty of patrolling 10 miles out to sea during the night. Inflexible was the first guardship followed by Kent.

Port Stanley, Falkland Islands, in 1914: Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Sturdee intended to coal his squadron and leave on Wednesday 9th December, heading south-west to Cape Horn.

The order he set for coaling was; Carnarvon, Bristol and Glasgow to coal first; then Invincible and Inflexible, with Kent and Cornwall coaling last. In addition Bristol needed repairs to her engines. All ships were to keep up steam to enable them to achieve 12 knots at 2 hours notice, with the allocated guardship ready for 14 knots at 30 minutes notice. Bristol was permitted to run her fires down to enable the repairs to be carried out.

Early on Tuesday 8th December Carnarvon and Bristol coaled, although Bristol’s coaling was delayed due to the deterioration in her collier’s coal, leading to a spin-off delay for the other ships. Inflexible began coaling. Neither Cornwall, Kent nor Macedonia had begun coaling.

The Battle:

At 7.50am the observation tower established by Canopus reported that two strange warships were approaching from the south. It was apparent that they must be ships from von Spee’s East Asiatic Squadron. Sturdee’s ships had been taken by surprise.

Von Spee is reported to have been reluctant to approach the Falkland Islands and was persuaded to make the raid, primarily aimed at the Falklands radio station, by the captain of the Gneisenau. Von Spee sent Gneisenau and Nürnberg ahead of the squadron to reconnoitre the Falklands and destroy the radio station with gunfire so that no warning could be passed on of their approach.

The British ships were busy coaling and preparing to leave that evening and so many false reports on the position of the German warships were circulating that little notice was taken of the warning. Glasgow received the message and fired a gun to attract the attention of the other ships. It was not for some twenty minutes that the British ships began to respond to the threat.

It was fortunate that Admiral Sturdee had required his ships to be at 2 hours notice of sailing. After the long journey from the Brazilian coast they might well have been permitted to shut their boilers down completely for repairs and maintenance work.

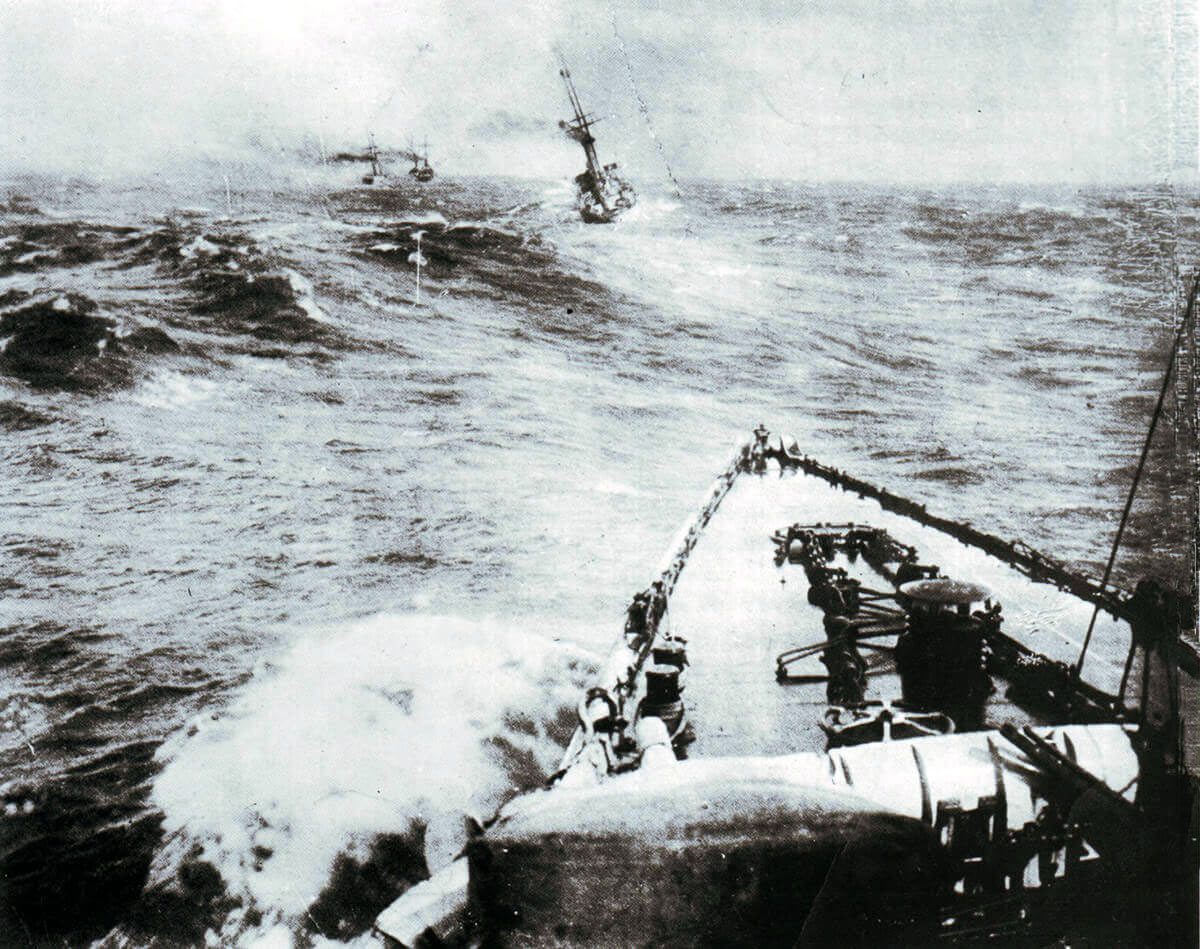

HMS Kent, Glasgow and Inflexible leaving Port Stanley in pursuit of the German squadron: photograph taken by Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant Duckworth RN from HMS Invincible at the beginning of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

At 8.30am ‘Action’ was sounded off and Sturdee’s squadron prepared to get under way, other than Bristol which could not be ready to move until 11am. Kent was due to take over as guard ship and was able to move off straight away with orders to join Macedonia at sea.

At around this time the signal station reported more smoke to the south-west, the rest of von Spee’s squadron. Macedonia was ordered back into harbour, being insufficiently armed for a sea battle with German warships.

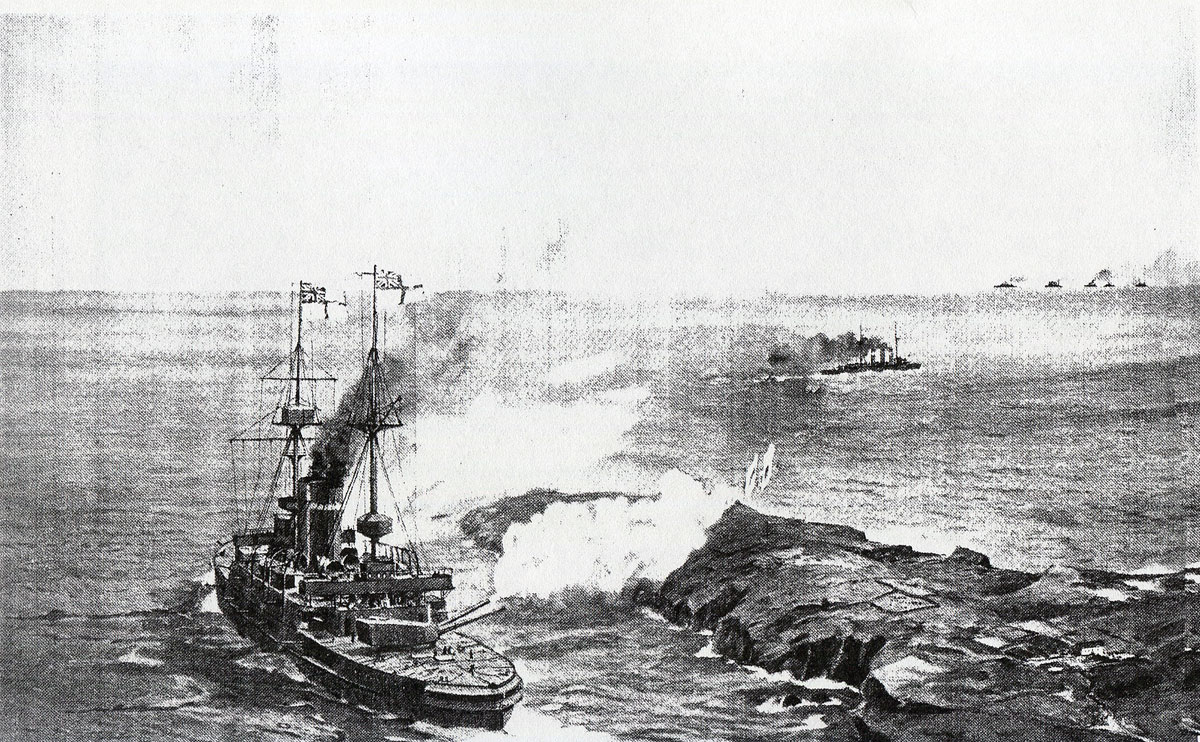

Gneisenau and Nürnberg headed for the radio station near Hooker Point. Canopus at 9am requested permission to open fire, having her gunnery control officer in a hut on high ground ashore. HMS Carnarvon was now under way and heading for the open sea.

HMS Canopus opens fire at the beginning of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

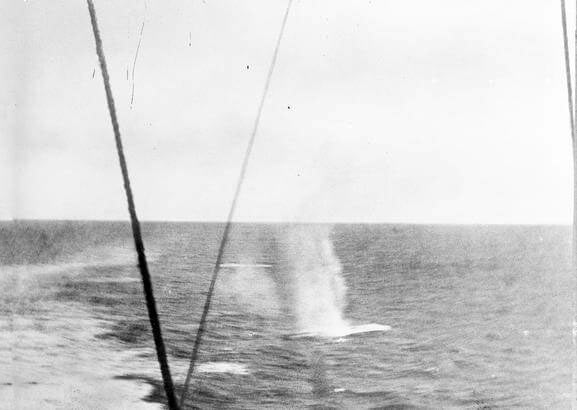

As Canopus opened fire the two German ships hoisted their ensigns and turned away to the south-east quickly, putting themselves out of range of Canopus’ guns. They then turned towards Kent, causing Sturdee to order Kent to return to harbour.

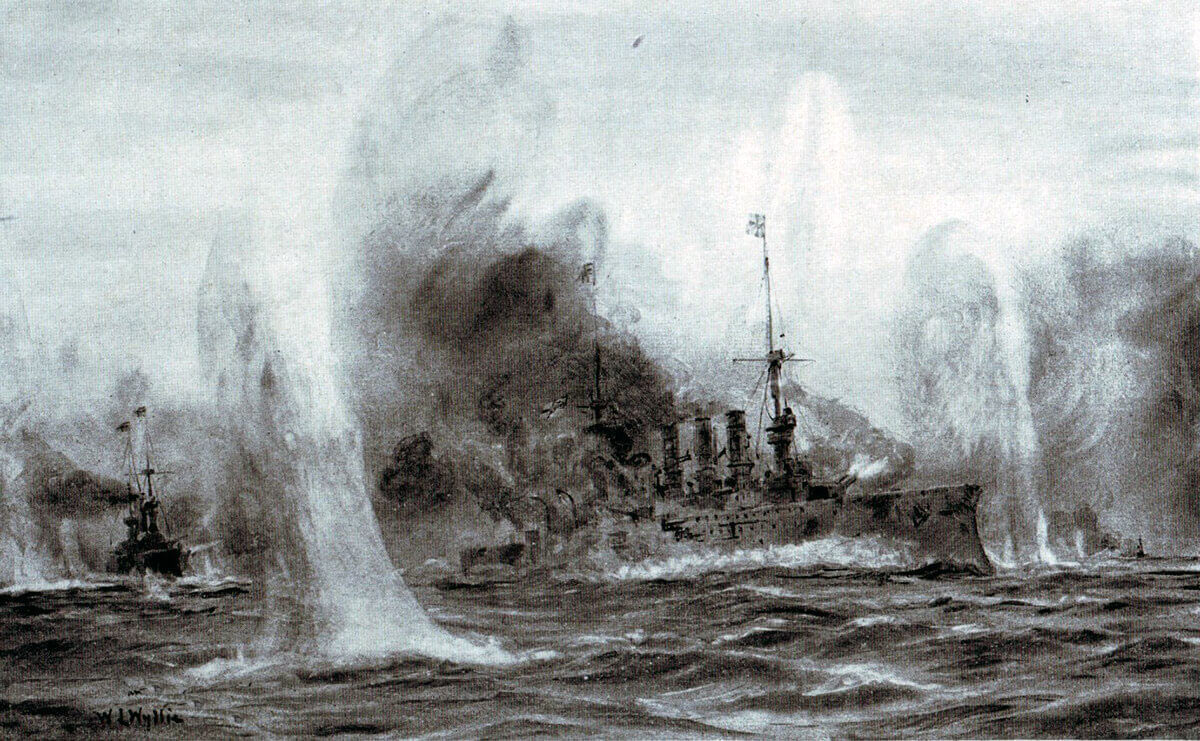

Shells fired by HMS Canopus splashing around SMS Gneisenau and SMS Nürnberg at the beginning of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

County flag of Kent hoisted on HMS Kent at the beginning of the Battle of the Falkland Islands 8th December 1914 in the First World War

The captains and crew on Gneisenau and Nürnberg saw the clouds of black smoke rising from Port Stanley harbour, as the British ships hurriedly fired up their boilers, indicating a substantial warship presence, and they possibly identified the tripod masts characteristic of British battle cruisers. In the face of such overwhelming British naval strength the two German ships turned and made off at high speed towards Scharnhorst and the rest of the squadron.

By 9.45am all the British warships, other than Bristol, had steam up. Glasgow was ordered to join Kent. Admiral Stoddart in Carnarvon took charge of the guard ships outside the harbour.

At 10am the main body of the British squadron weighed anchor and headed out of the harbour, Inflexible leading Invincible and Cornwall. Glasgow reported the German ships to be heading south-east, apparently at full speed. Glasgow and Kent set off in pursuit.

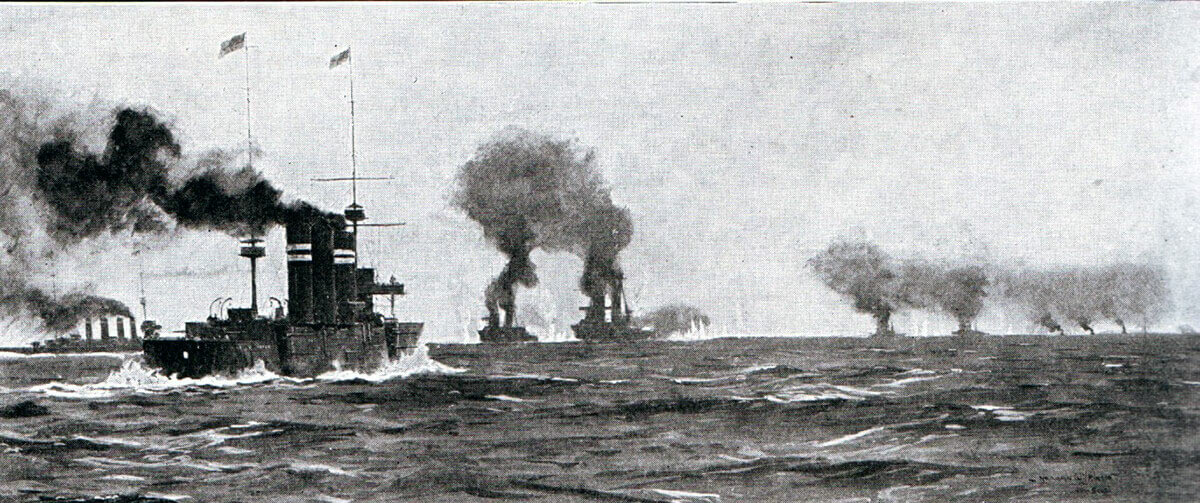

Opening stage of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War, as the British ships leave Port Stanley in pursuit of the German squadron. The action is foreshortened; the German ships in the distance far right; Invincible and Inflexible centre; Glasgow left and Cornwall centre left

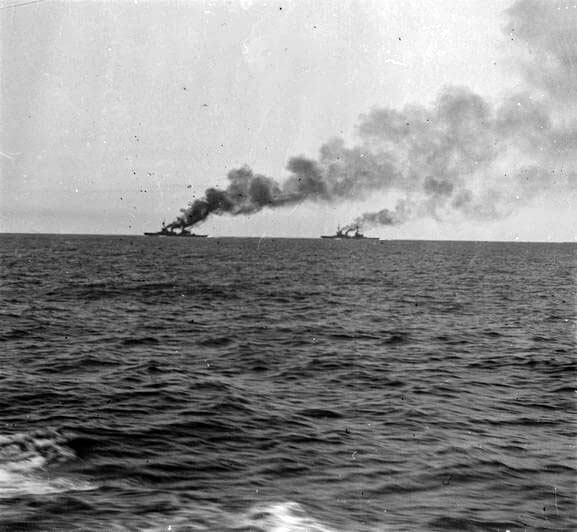

The weather now cleared and visibility over a calm blue sea was complete. As the British ships left harbour the rising smoke smudges on the horizon showed the positions of the five German warships. Von Spee joined Gneisenau and Nürnberg and the whole squadron was making off to the south-east, now fifteen miles away.

Photograph taken from the masthead of HMS Invincible by Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant Duckworth RN as the chase began in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War. The smoke from the German ships can be seen on the horizon

Admiral Sturdee signalled ‘General Chase’, the dramatic signal that gives a complete discretion to each captain to do whatever he considers necessary to catch the German ships.

Commander Townsend second in command of HMS Invincible at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

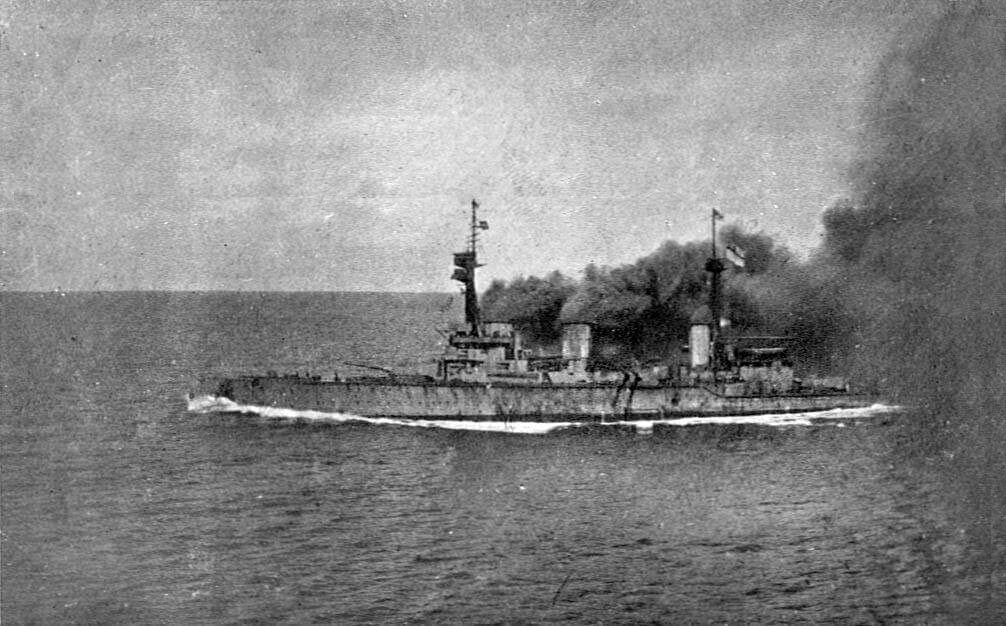

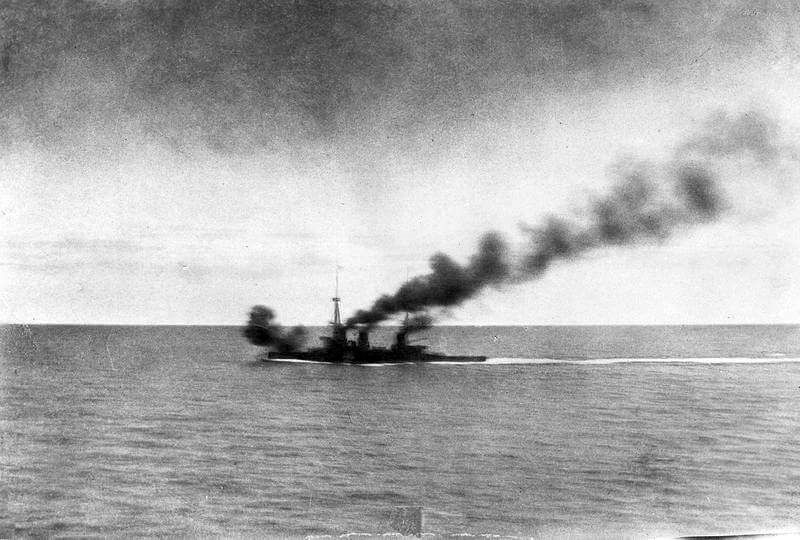

A major feature of the coal powered warships of the period was the amount of black smoke the enormous boilers produced. The greater the acceleration of the ship the more smoke she gave out of her funnels. The two battle cruisers were capable of 28 knots, at which speed clouds of black smoke surrounded each ship and any other ship following.

By 11am Admiral Sturdee could no longer see the German ships, due to the amount of smoke belching out of the funnels of Invincible and Inflexible. Glasgow, leading the chase, signalled that the German squadron was now 12 miles away. The British ships were fast catching up. Sturdee ordered a reduction of speed to 24 knots to reduce the smoke cloud and to enable the other cruisers to catch up. Glasgow was ordered to remain 3 miles ahead to keep watch on the pursued ships well clear of the smoke cloud.

While 24 knots was a reduction in speed for Invincible and Inflexible, it was the maximum speed or even too fast for the British light cruisers and significantly faster than the speed the German ships could maintain, particularly after months at sea with only running repairs to their machinery.

The essence of the order ‘General Chase’ was to give complete discretion to individual captains. As soon as Admiral Sturdee gave orders on speed and station ‘General Chase’ was automatically rescinded.

HMS Inflexible and Invincible seen from HMS Kent during the pursuit of the German squadron in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Carnarvon and Cornwall were lagging behind by some five miles, in spite of the reduction in speed (the best they could do was Carnarvon 20 knots and Cornwall 22 knots). Soon after 11am Sturdee ordered a further reduction for the two battle cruisers and HMS Glasgow to 19 knots. Glasgow signalled that the German squadron was doing only 15 knots and this enabled Sturdee to close up his ships while comfortably overtaking von Spee. The German ships were now well in sight with their upper works visible on the horizon. At around 11.30am Sturdee ordered a speed of 20 knots.

Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee RN, British commander at the Battle of the Falkland Islands 8th December 1914 in the First World War

In Port Stanley the engine room staff of HMS Bristol managed to get her boilers fired up and she was under way. Bristol signalled the flag that two ladies on land reported spotting three further ships, which turned out to be von Spee’s hospital ship and colliers. Sturdee ordered Captain Fanshawe of Bristol to take Macedonia and destroy the colliers.

With some time to go before the German squadron came in range, at 11.30am Sturdee ordered his ships’ companies be dismissed below to change from their coaling rig and have a meal.

With the German squadron at such a distance it was not possible to determine its exact course. The British ships were sailing on a roughly parallel course heading east. At 11.15am Glasgow signalled that the Germans were altering to starboard. Sturdee turned to east by south, continuing on a parallel course. 5 minutes later Sturdee turned a further 2 points to south-east by east, a course converging with the German squadron.

Carnarvon was only making 18 knots not the 20 she claimed to be capable of so that she and Cornwall were still falling back, now being 6 miles in the rear.

At 12.20pm the Germans again turned to starboard and it became apparent that they were breaking up the close formation they had maintained during the chase. They were heading south- east and were becoming covered by their own smoke.

Sturdee decided to attack. The two British battle cruisers opened up the distance between them and increased speed to 25 knots, quickly catching up with Glasgow. Sturdee issued the order to engage.

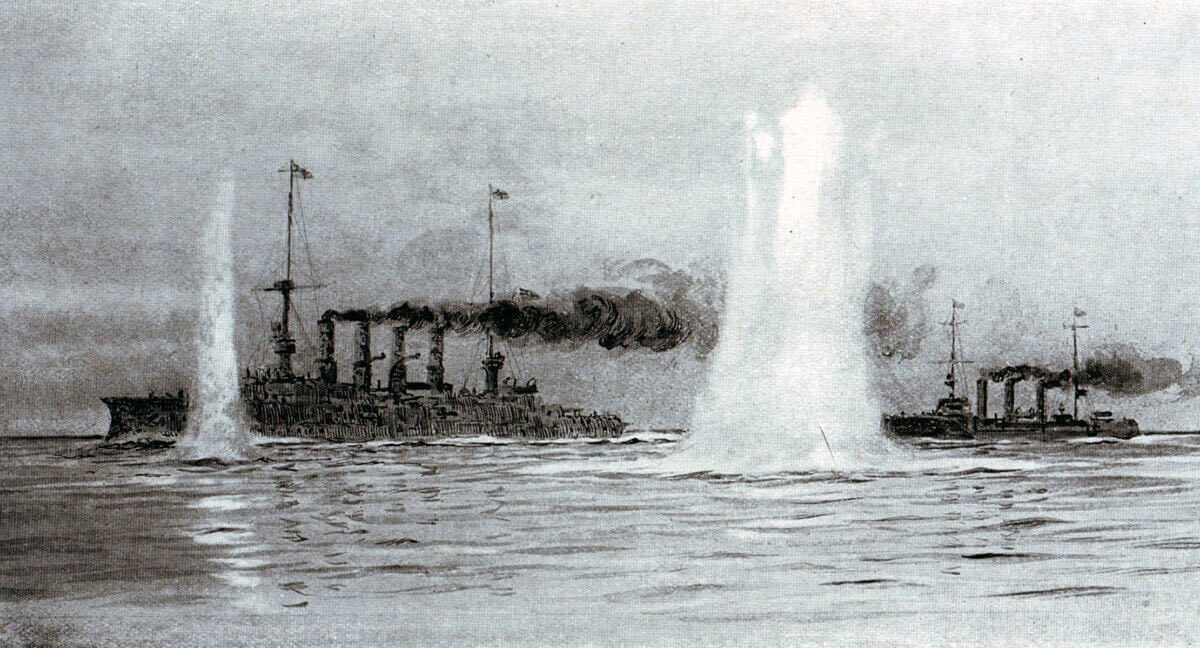

SMS Leipzig was the slowest of the German ships and was in the rear of von Spee’s squadron. At 16,000 yards (9 miles) Inflexible opened fire on Leipzig, quickly joined by Invincible. The two battle cruisers turned 2 points to starboard in order to close and increased to full speed. Shells were landing around the Leipzig so that she was several times concealed by shell splashes.

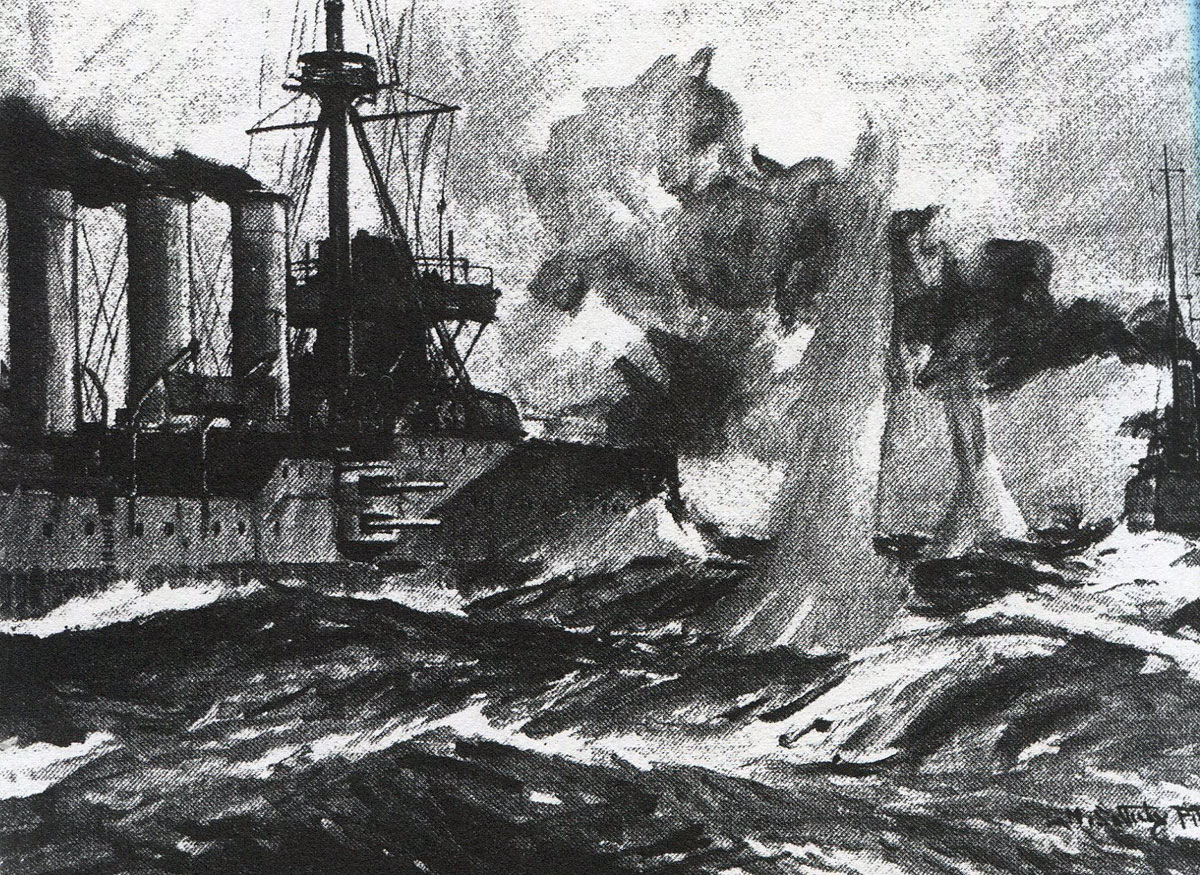

HMS Invincible and Inflexible open fire on von Spee’s squadron during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

Seeing that it was a matter of time before his light cruisers were overwhelmed by the British battle cruisers, von Spee at 1.20pm ordered those ships to scatter and head for the South American coast, there to resume their role of sinking Allied commercial shipping, whilst Scharnhorst and Gneisenau turned into line ahead to the north-east to give battle to the British squadron.

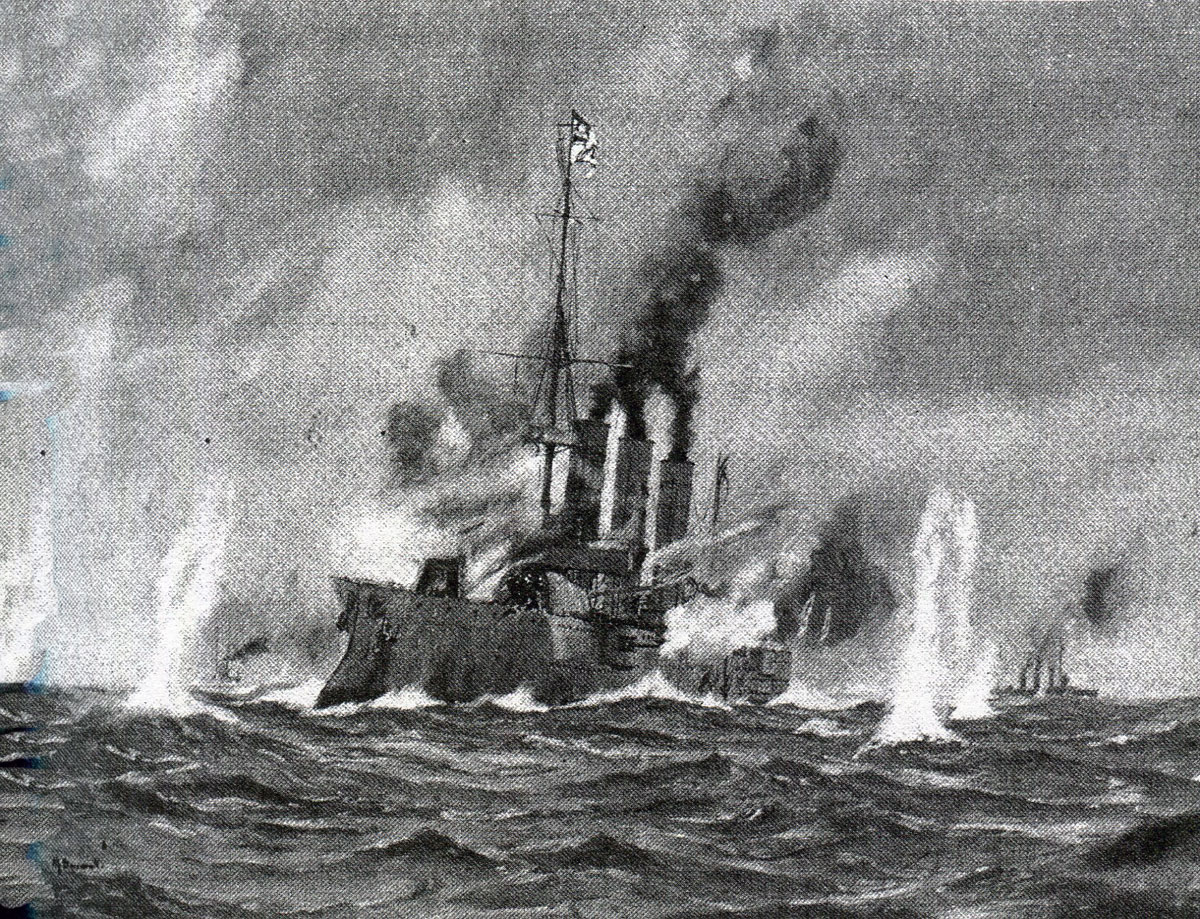

HMS Invincible under way and giving off clouds of black smoke at the beginning of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

The three German light cruisers turned to starboard and headed off to the South. Sturdee’s plans provided for this eventuality. The British cruisers pursued their German opposite numbers, while Invincible and Inflexible dealt with the two German armoured cruisers.

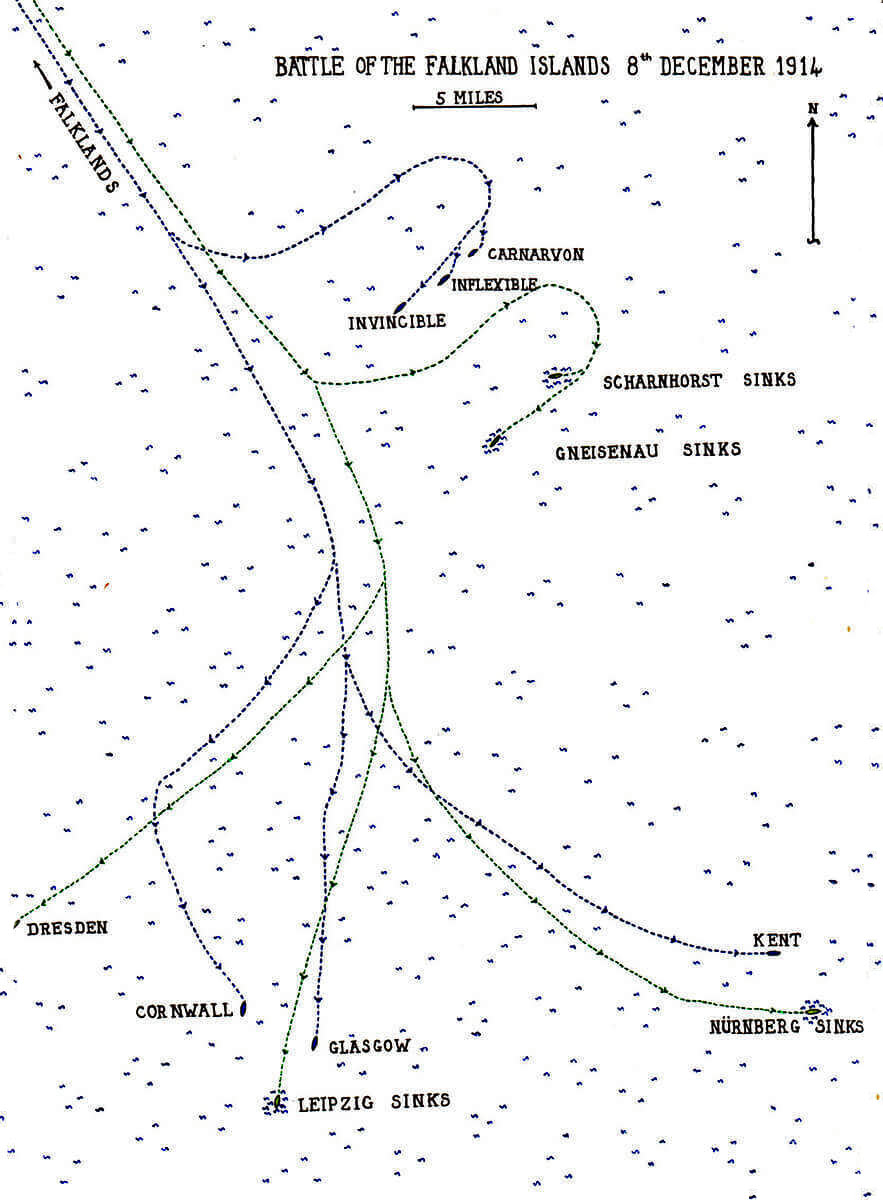

Map of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: map by John Fawkes

Kent, Cornwall and Glasgow turned to starboard to cut the corner in pursuit of Dresden, Nürnberg and Leipzig.

The two battle cruisers turned 7 points to port into line ahead on the beam of von Spee’s two armoured cruisers and did so before the Germans completed their turn.

At 1.20pm the British ships opened fire, Invincible on Gneisenau and Inflexible on Scharnhorst. Gneisenau, the faster of the two German armoured cruisers, had been in the van during the chase. She slowed to permit Scharnhorst to take the lead and open fire. But at 14,000 yards (8 miles) the range was too great for the German guns, their shells falling 1,000 yards short.

HMS Inflexible opens fire on SMS Gneisenau during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the FirstWorld War: photograph taken by Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant Duckworth RN from HMS Invincible. Smoke from HMS Invincible can be seen at the top of the photograph

Von Spee altered his course towards the British, the range quickly falling, and at 13,000 yards (7.5 miles) he turned back so that the Germans were on a course parallel to the British ships. The two German ships opened fire. A shell fired at its extreme range hit Invincible; remarkable shooting.

At 1.44pm Sturdee altered course to port to take his ships out of range of the German guns on a course parallel with von Spee.

The German ships were firing with restraint, their ammunition supply being unreplenished since the Coronel battle.

Shots fired by SMS Scharnhorst landing in the sea behind HMS Invincible during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: photograph taken by Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant Duckworth RN from HMS Invincible

The British battle cruisers were severely hampered by their own smoke, the after turrets on Invincible and all the guns on Inflexible being masked by the dense black clouds. Consequently no hits were now being scored by either side.

By 2pm the range between the British and German ships opened to more than 16,000 yards (9 miles) and both sides ceased firing.

SMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau engaged by HMS Invincible and Inflexible during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

At 2.05pm Sturdee turned 8 points to starboard in order to close the range. The change in direction caused the two British battle cruisers to be immersed in the heavy smoke and sight was lost of the two German armoured cruisers.

Once clear of the smoke Sturdee saw that the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had turned 10 points to starboard and were heading south after the German light cruisers, already 17,000 yards (9.65 miles) away. Sturdee turned and increased speed, now in a stern chase.

By 2.45pm the British battle cruisers closed the distance on the Germans to 15,000 yards (8.5 miles). Sturdee turned slightly to port to bring his broadside into play and opened fire.

After five minutes von Spee turned 9 points to port into line ahead. Sturdee responded with a 6 point turn to port, bringing the ships broadside to broadside. The German ships opened fire.

The two lines were now on a converging course with the range closing. It seemed that von Spee was intent on bringing his secondary armament into action.

HMS Invincible and Inflexible in action at the beginning of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Eric Tuffnell

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau possessed secondary armaments of 6 inch guns while the secondary armament on Invincible and Inflexible comprised 4 inch guns.

By 2.59pm the range was down to 12,500 yards (7 miles) and the German ships opened fire with their 6 inch guns.

For ten minutes the range remained at this distance and each side scored hits on the other, with the hottest fire of the action, although the heavy smoke from the British ships interfered with the spotting for both sides.

Little damage was being inflicted on the British ships while the German ships were suffering considerable punishment. Scharnhorst was on fire in a number of places, one funnel shot away and her fire slackening, while Gneisenau was beginning to list.

At 3.15pm in order to clear the heavy smoke Sturdee turned his line nearly back on itself through 18 points. He was now to windward and free of the smoke cloud. Both battle cruisers were free to fire on the Germans with a full view of the fall of shot.

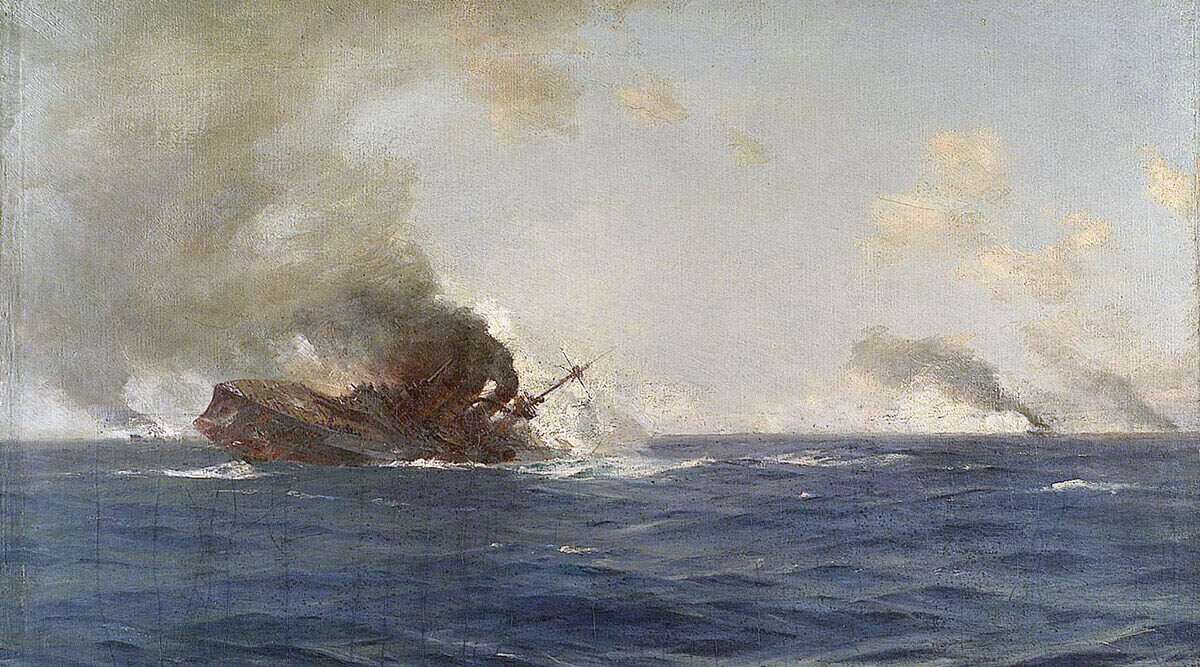

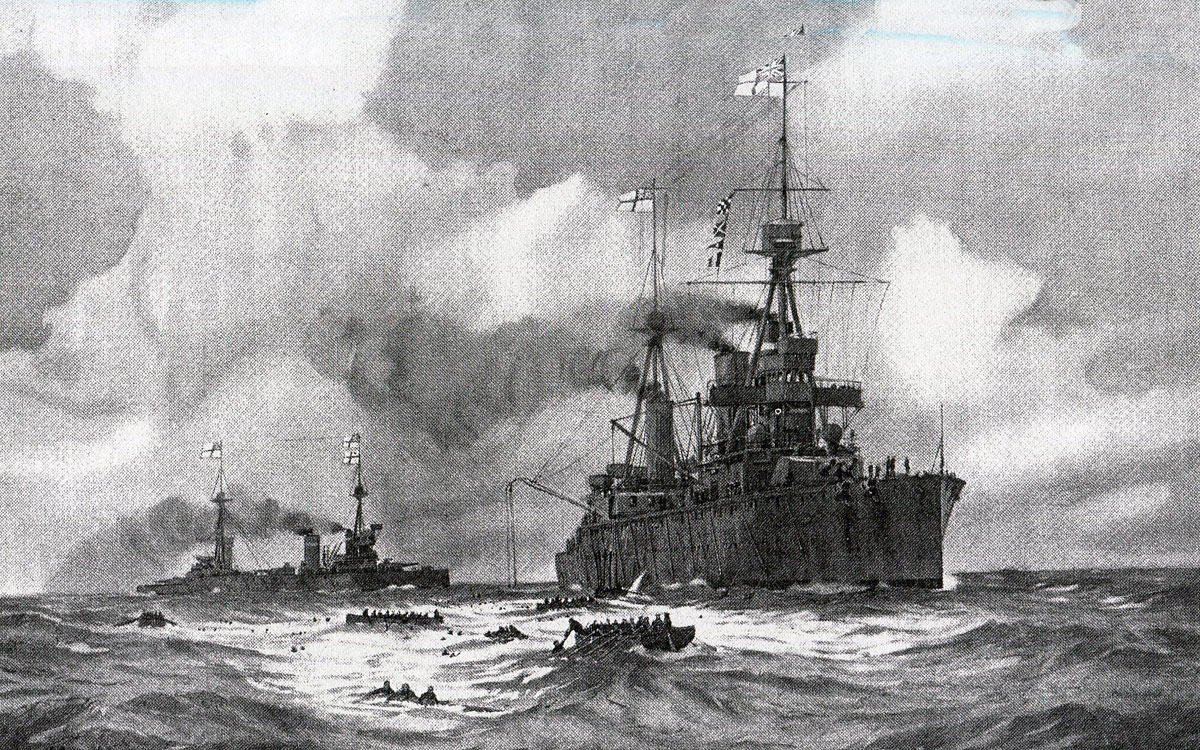

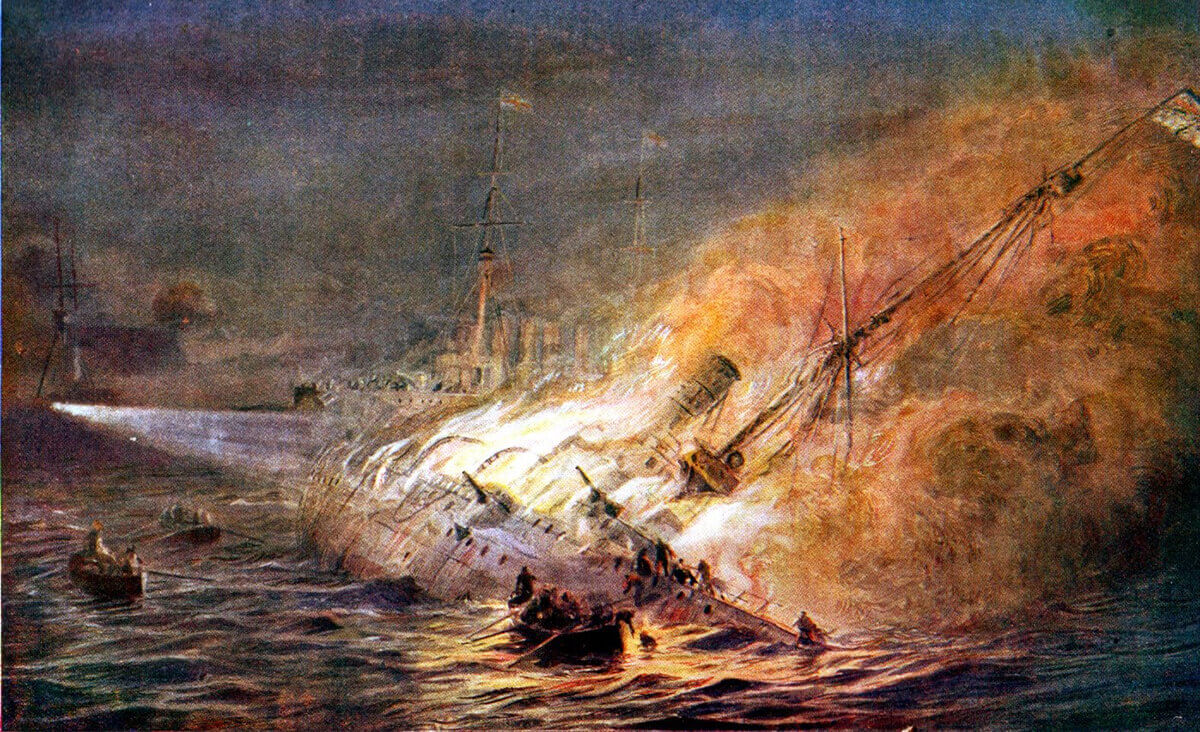

SMS Scharnhorst sinking at the end of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Thomas Somerscales

At about 3.20pm as the British ships approached the Germans Sturdee turned 4 points to port, to head across von Spee’s wake. Strikes on the two armoured cruisers continued, Gneisenau’s list was such that her secondary armament was forced to cease firing. Scharnhorst’s was suffering increasing damage.

At 3.30pm, as the two forces were passing each other, von Spee turned 16 points to starboard heading to the north-west and making to cross the bows of the British ships. This enabled Scharnhorst to bring her unengaged broadside into action. But she was in a terrible state.

Assistant Paymaster Gordon Findlay, who served on HMS Invincible from her wartime commissioning on 2nd August 1914 described Scharnhorst: ‘Her upper works seemed to be but a shambles of torn and twisted steel and iron, and through the holes in her side, even at the great distance we were from her, could be seen dull red glows as the flames gained mastery between the decks’ (A Naval Digression by GF).

British postcard of the Battle of the Falklands fought on on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

As the German ships wheeled Sturdee countered with a 2 point turn to port. The range now closed to 12,000 yards (6.8 miles) and was falling. Von Spee was forced to turn away under the heavy fire. Sturdee also turned and quickly was out of range of the German secondary armament.

During these manoeuvres Inflexible took the lead and for the first time was free of the flagship’s smoke. She directed her fire on Scharnhorst as did Invincible. The German flagship was losing speed and the British ships closed in on her.

SMS Gneisenau in action during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

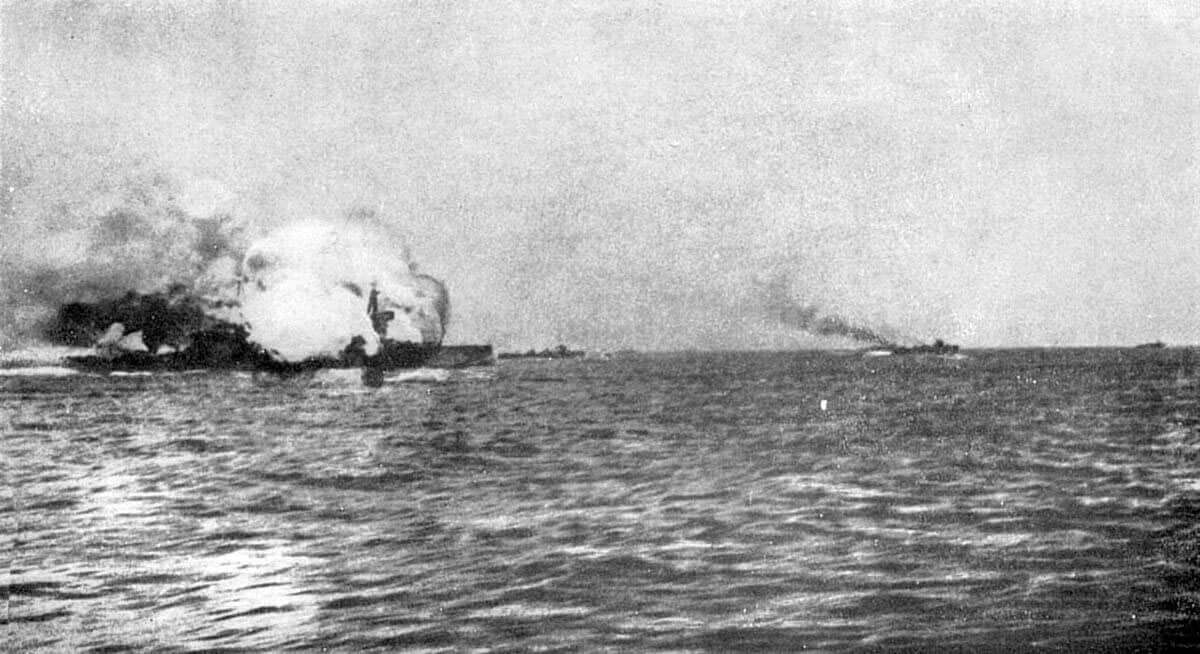

At around 4pm Scharnhorst suddenly ceased firing and lurched to starboard. Inflexible turned back to deal with Gneisenau while Invincible remained with Scharnhorst. Her flag still flying the German flagship turned over. Von Spee’s last signal was to Gneisenau to try and save herself. At 4.17pm Scharnhorst sank. No rescue operation was possible due to the continued action with Gneisenau and all her crew were lost.

Sturdee turned Invincible to starboard to join the attack on Gneisenau, but finding the smoke cloud obscuring his vision of the German ship, turned back to starboard. Now on an opposite course Invincible could see Gneisenau and engaged her at around 11,000 yards (6.25 miles).

Both battle cruisers were now striking Gneisenau. Her number 1 turret was out of action and a stokehold was flooded.

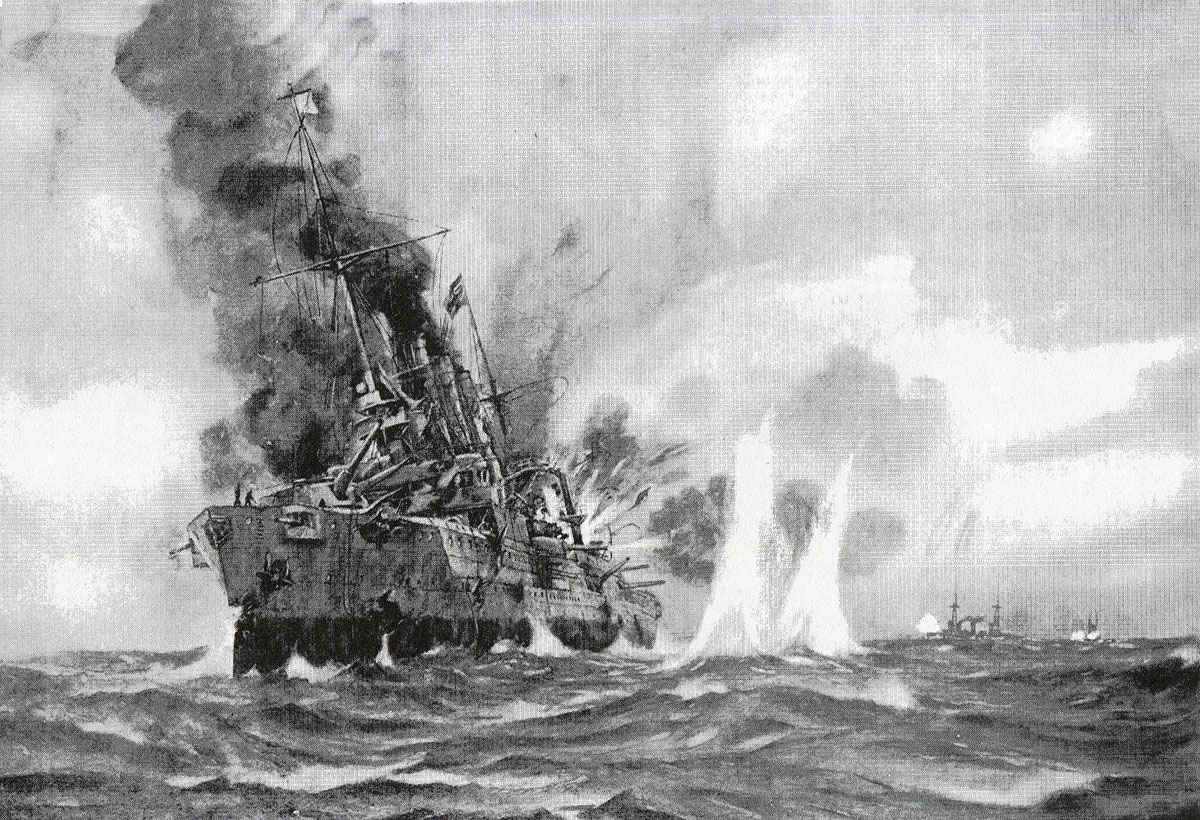

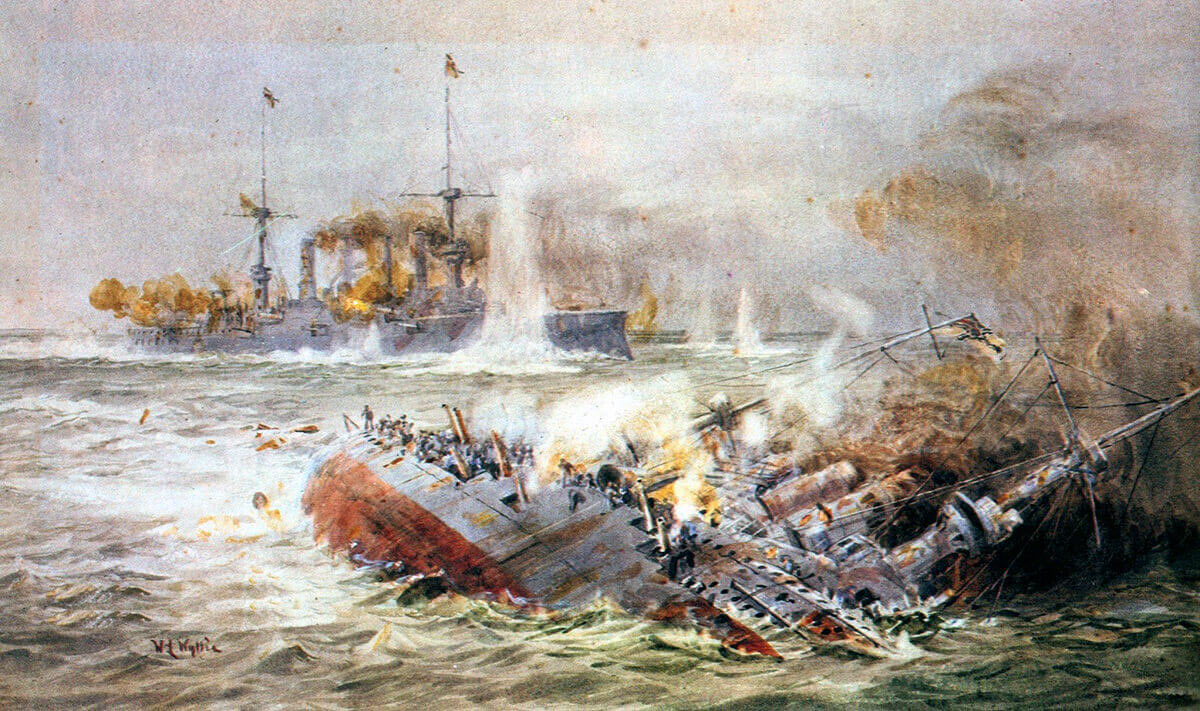

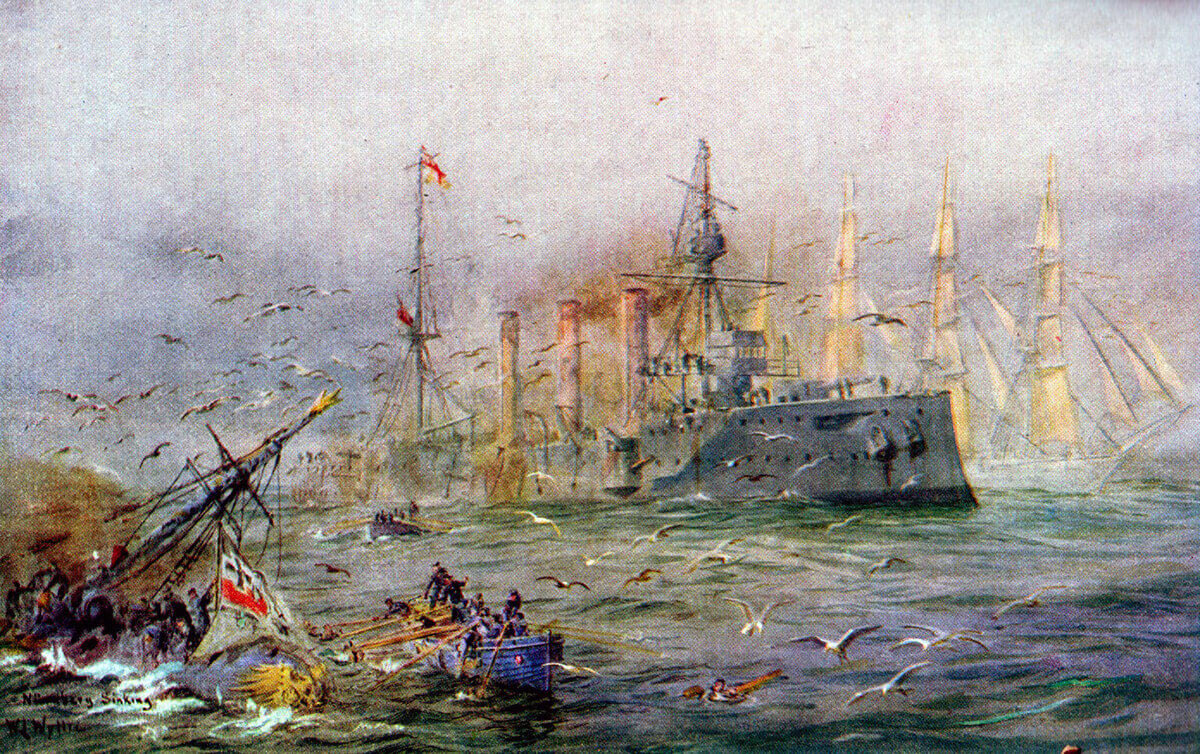

SMS Scharnhorst sinking (foreground) and SMS Gneisenau at the end of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

Invincible circled to escape the ubiquitous smoke and found herself heading west on a course diverging from Gneisenau.

The slow speed of the German ship and the manoeuvring of the battle cruisers enabled Carnarvon to come up and join the attack. Sturdee ordered the other two ships to form line behind Invincible. But again Inflexible found herself unable to shoot at Gneisenau due to the flagship’s smoke and turned to port, acting without orders.

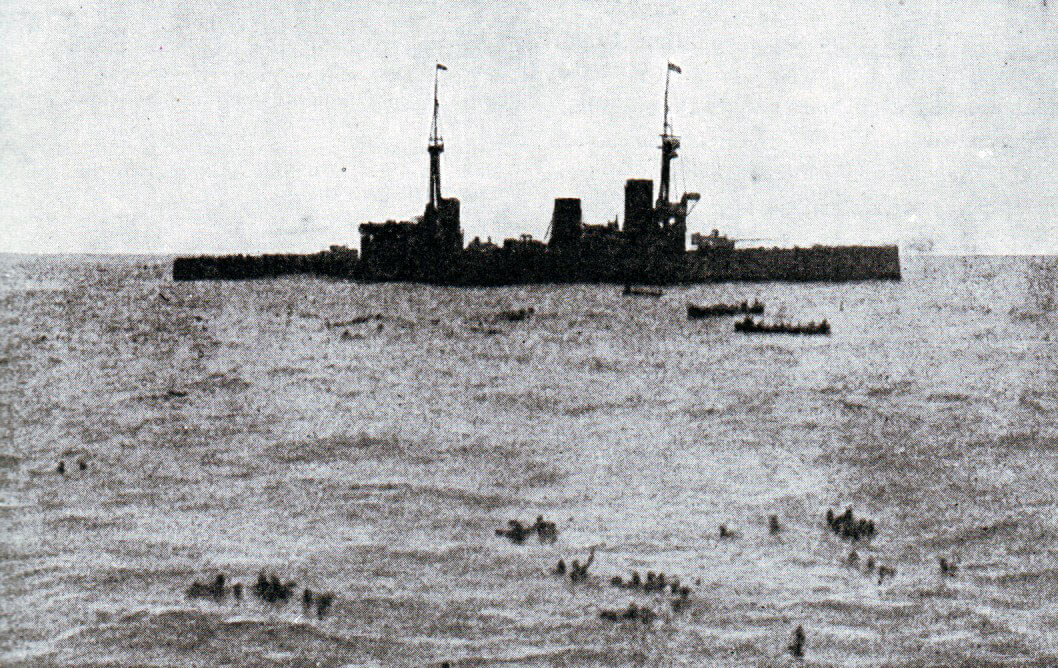

Rescuing the survivors from SMS Gneisenau at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

All three British ships were firing on Gneisenau, Invincible and Carnarvon on her starboard quarter and Inflexible to her rear.

The weather was deteriorating with rain falling and visibility reducing significantly. The German ship was now in a poor way. She had lost a funnel and her speed had fallen to 8 knots. She was on fire fore and aft and had fired away all her 8 inch ammunition.

At 5.30pm Gneisenau turned towards Invincible and stopped. The two battle cruisers closed in. The German ship was listing heavily to starboard. Her firing was sporadic and then ceased. Sturdee thought she must have struck and ordered the ‘Cease Fire’. Then Gneisenau resumed firing and the British ships fired back.

At about 5.45pm Gneisenau ceased firing again and was seen to be sinking. The British ships closed to around 3,500 yards (2 miles) but before they could approach any further Gneisenau capsized. The remnants of her crew could be seen walking along the keel and then she sank.

The captain opened the sea cocks on Gneisenau, ensuring she sank quickly and took many of the crew with her. The British ships rushed to the area and lowered boats, so that around 200 of her crew were picked up.

HMS Inflexible picking up survivors from SMS Gneisenau at the end of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: photograph taken by Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant Duckworth RN from HMS Invincible

Once the action with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau was finished Sturdee radioed his cruisers to see how they had fared in their pursuit of the German light cruisers. He received no reply from Kent and Cornwall and eventually a report from Glasgow.

German Light Cruisers:

The three German light cruisers, Dresden, Nürnberg and Leipzig on leaving the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in compliance with Admiral von Spee’s order at 1.25pm headed south. They were around twelve miles ahead of their British pursuers, Glasgow, Kent and Cornwall.

The maximum speeds of the British and German cruisers were: Dresden the fastest with a top speed of 27 knots, Glasgow with 25 knots, Nürnberg with 23.5 knots, Kent, Cornwall and Leipzig with 23 knots.

While these were the official maximum speeds for the class of ship, the German cruisers suffered from a significant disadvantage. Posted to the China station the German ships were inadequately maintained and began the war in a poor state of repair. Since June 1914 von Spee’s ships had been constantly at sea and undergone a major battle. The strain on the machinery and in particular the boilers were now showing with a corresponding loss of efficiency.

The German light cruisers were significantly outgunned by the two British armoured cruisers, Kent and Cornwall with their 6 inch guns against the German 4.1 inch guns. The German ships were low on ammunition, particularly those that had fought at Coronel and been involved in the bombardments in the Pacific.

SMS Nürnberg, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

When the chase of the German light cruisers began at 1.30pm the three ships broadly kept together, Nürnberg in the centre, with Leipzig about a mile on her starboard and Dresden around 4 miles ahead on her port bow.

Glasgow overtook Kent and Cornwall in the pursuit, with Dresden in her sights. Captain Luce in Glasgow then decided that his initial attack should be on Leipzig. Glasgow was some 12,000 yards (6.8 miles) behind Leipzig when she opened fire with her forward 6 inch gun. Leipzig turned to starboard and returned the fire with her broadside. Glasgow turned aside and opened the range, Leipzig turned back and the chase resumed. Glasgow repeated the process and so reduced her distance from Leipzig, while Kent and Cornwall pounded along behind, slowly closing the gap.

Soon after 3.30pm the German light cruisers scattered, Nürnberg turning away to port and Dresden disappearing to the south-west. Kent and Cornwall agreed between them that Kent should take on the Nürnberg, while Cornwall, assisted by Glasgow, dealt with Leipzig.

SMS Leipzig, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

At around 4.30pm the two British armoured cruisers opened fire, but they were just out of range. Nürnberg turned east followed by Kent and Leipzig turned to south-south-east, pursued by Cornwall and engaging Glasgow.

HMS Glasgow opens fire on SMS Leipzig in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

SMS Leipzig:

By about 4.45pm Cornwall was straddling Leipzig with her gunfire. Glasgow circled round to join her on Leipzig’s port so that both British ships were firing into the same side of the German ship. Within fifteen minutes Leipzig was badly damaged and her gunnery lieutenant killed, a severe handicap to effective control of her firing.

At around 5pm Cornwall turned sharply to starboard and brought her port broadside into action. Leipzig was now moving so slowly that Cornwall and Glasgow were able to circle her and fire into her at whichever angle and range they chose.

At around 6pm the rain increased and Captain Luce in Glasgow gave the order to finish Leipzig off. The two British ships closed to 8,000 yards (4.5 miles) and Cornwall opened fire with lyddite, setting Leipzig ablaze.

SMS Leipzig under fire in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Cornwall and Glasgow closed the range, Leipzig continuing to fire back until 7pm when her guns fell silent, all her ammunition expended. She had fought for four hours against the two British ships and was now a wreck, with fires all along her hull and superstructure. But she still flew her ensign.

Luce waited for half an hour to see if the German ship would surrender. As the German ensign still flew he ordered the British ships to resume firing. On board the Leipzig the captain ordered the sea cocks to be opened and 150 of the surviving crew assembled amidships between the fires to await rescue. Many of these men were killed by shellfire until they displayed two green lights. The British ships took this as an indication of surrender and ceased fire.

Signals were made to the German ship but there was no reply. Cornwall and Glasgow launched their boats and began to pick up those survivors who had jumped into the sea.

SMS Leipzig sinking at the end of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

At 9.23pm Leipzig turned over and sank. Although the British boats were promptly launched and moved in to pick up survivors only five officers and thirteen seamen were rescued alive, not including the captain. The choppy cold waters of the South Atlantic were too much for the remainder who had managed to get off the ship.

In the fight with Leipzig Cornwall was hit eighteen times and was listing to port but had no casualties. Glasgow was hit twice and had one man killed and four wounded.

SMS Nürnberg:

At 4.30pm Kent began the chase of Nürnberg, 7 miles behind the German ship. Kent’s nominal maximum speed was 22 knots, but she was notoriously a bad steamer. Nürnberg was expected to achieve 22.5 knots, but she put so much strain on her boilers, which were in need of a complete overhaul after months at sea, that two burst, reducing her speed to 19 knots.

Stokers at work on HMS Kent during the ship’s pursuit of SMS Nürnberg in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Kent had no opportunity to take on coal at Port Stanley before the action began so that she was very short of fuel. Captain Allen, the captain of the Kent, ordered that every item of wood be taken to the engine room for the stokers to load into the burners. Woodwork was stripped from all the fittings and even the officers’ trunks were burnt. It is claimed by the ship that they managed to achieve 25 knots in this way.

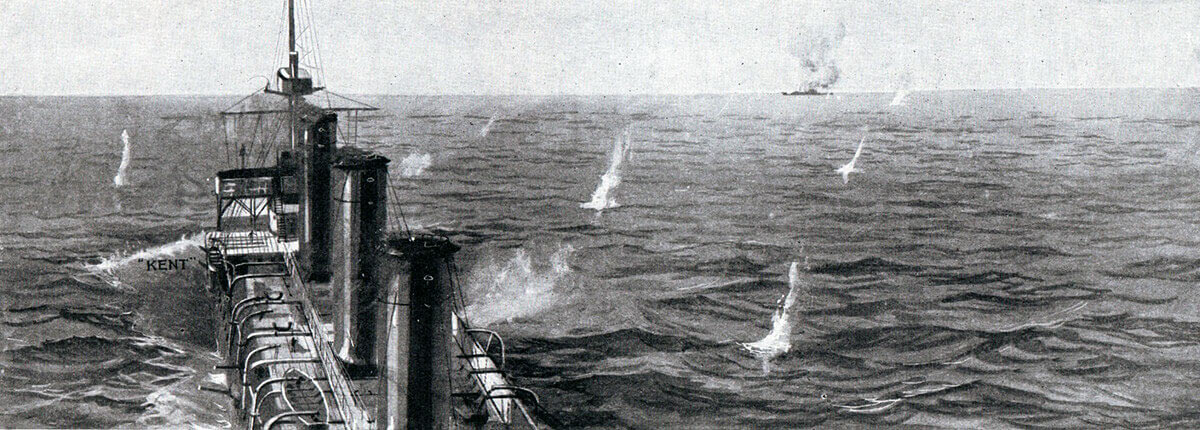

By 5pm Kent was within 12,000 yards (6.8 miles) of Nürnberg. Nürnberg opened fire with her rear 4.1 inch guns, her shots falling close around Kent, but achieving only one hit. Kent replied with her forward 6 inch gun, but the range was too great.

HMS Kent in action against SMS Nürnberg during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Charles de Lacy

By 5.30pm Kent was coming up to Nürnberg and at 5.45pm Nürnberg turned 8 points to port and brought her broadside into action. Kent was not interested in a long range duel. The vibration caused by her speed was making range finding almost impossible and the light was failing.

Damage to the hull of HMS Kent caused by shell-fire from SMS Nürnberg during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Kent turned 6 points to port onto a converging course. The range quickly fell to 6,000 yards (3.5 miles) and Kent’s shooting became more effective.

HMS Kent engaging SMS Nürnberg during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

By 6pm the range was 3,000 yards (1.7 miles) and Kent’s larger guns were impacting on the German cruiser. Nürnberg turned away to starboard. Kent also turned but not so sharply so that the range increased, but her hits on Nürnberg continued.

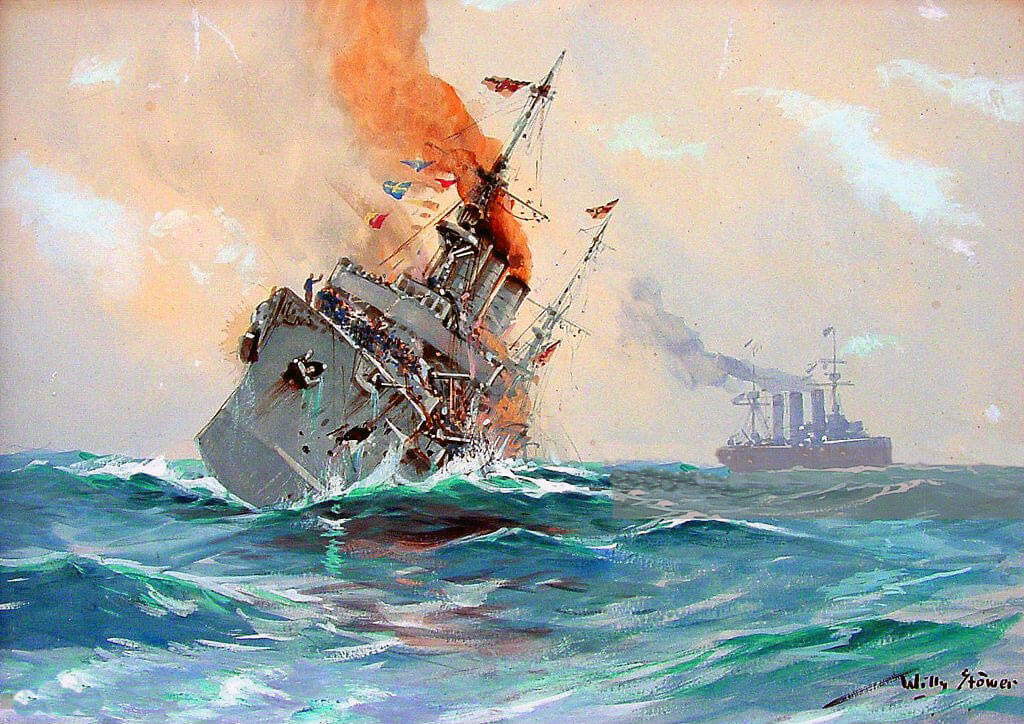

SMS Nürnberg sinking at the end of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Willy Stoewer

By 6.10pm Nürnberg was losing speed, on fire and with only two guns operational. Kent was able to pass her and turn to starboard to cross in front of her. Nürnberg turned to port. This gave Kent the opportunity, as she crossed Nürnberg’s bow, to rake her with her starboard batteries.

The consequences were devastating. The range was only 3,500 yards. Two 6 inch shells destroyed Nürnberg’s forward turret. Kent ran past Nürnberg and turned away enabling her port batteries to open fire.

SMS Nürnberg sinking at the end of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

By 6.25pm Nürnberg was stationary and silent. Kent ceased firing. Nürnberg was listing heavily and down at the stern. She was burning fiercely under the bridge and there was no sign of any crew. Kent approached to 3,300 yards (1.8 miles). She saw that Nürnberg was still flying her ensign. Kent resumed firing but 5 minutes later the ensign was hauled down.

Damage to the officers’ heads on HMS Kent caused by shell-fire from SMS Nürnberg during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Kent’s boats had been damaged in the action, but two were repaired sufficiently to be launched. Soon after, at around 7.30pm, Nürnberg turned over to starboard and sank. A search for survivors was maintained until 9pm, by which time it was dark. Seven members of Nürnberg’s crew were picked up alive.

Shell hole in a casemate on HMS Kent made during the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War. Sergeant Mayes RMA stands to the left of the hole

In the action with Nürnberg Kent was hit forty times. One hit wrecked the radio room. Another round hit a casemate and nearly ignited rounds waiting to be fired. The situation was retrieved by Royal Marine Artillery Sergeant Maye. Kent suffered four men killed and twelve wounded.

A sailing ship passes the battle between HMS Kent and SMS Nürnberg, sinking in the left foreground, at the end of the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

German Colliers:

HMS Bristol was already fifteen miles out of Port Stanley following the rest of the British squadron, when Captain Fanshawe received the order to seek out the German ships spotted by the two Falkland Island ladies. Bristol turned west – south – west and at 12.30 met with Macedonia. After some time in an unsuccessful search a report was received from the Islands that the German ships had been seen from Fitzroy. Bristol and Macedonia turned east by south and soon saw the smoke of the escaping ships.

Of the three German ships the hospital ship Seydlitz made off on her own. The two ships Bristol and Macedonia were now following were the colliers Baden and Santa Isabel.

At 3.30pm Bristol and Macedonia overtook the two German colliers and firing a gun ordered them to stop. Although the ships contained a large quantity of coal and other stores Fanshawe’s instructions were to ‘sink the transports’. He had no knowledge as to the outcome of the action fought by the other ships of the squadron and at 7pm in accordance with his instructions, after removing the crews, he sank the Baden and the Santa Isabel.

SMS Dresden:

Once he established radio contact with the British cruisers Sturdee enquired which direction Dresden had taken when she made off. The pursuit and destruction of the other German ships had been so all-absorbing and taken so many twists and turns that the cruisers were unable to provide Sturdee with any reliable information.

Eight colliers were being escorted to Port Stanley by the auxiliary merchant cruiser Orama. Sturdee despatched Carnarvon to the north to escort these ships in.

Sturdee took the two battle cruisers in a sweep towards Staten Island at the entrance to the Beagle Channel, ordering Bristol to follow on, to see if he could catch Dresden attempting to make it back into the Pacific.

SMS Dresden, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

At 11.25pm Sturdee signalled Glasgow and Cornwall to make for the Magellan Straits to intercept Dresden. The answer was that both ships had fired off nearly all their ammunition and that Cornwall was very low on coal. Both were ordered into Port Stanley.

After searching in the area of Staten Island Sturdee moved north and on 10th December 1914 finally returned to the Falkland Islands, to find that Kent had returned after sinking Nürnberg.

On 13th December 1914 Sturdee was busy coaling and repairing his ships in Port Stanley when he received news in the early hours that Dresden had been in Punta Arenas, the Chilean port at the western end of the Beagle Channel, on 10th December.

Sturdee sent his ships after Dresden as they were made ready. On arrival at Punta Arenas on 16th December it was found that Dresden had left after being permitted to coal by the Chilean authorities.

The Admiralty now ordered Sturdee to return to Britain with the two battle cruisers, which were to resume their duties with the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow. Admiral Stoddart and the cruisers were to continue the search for Dresden and other German warship and auxiliary cruisers.

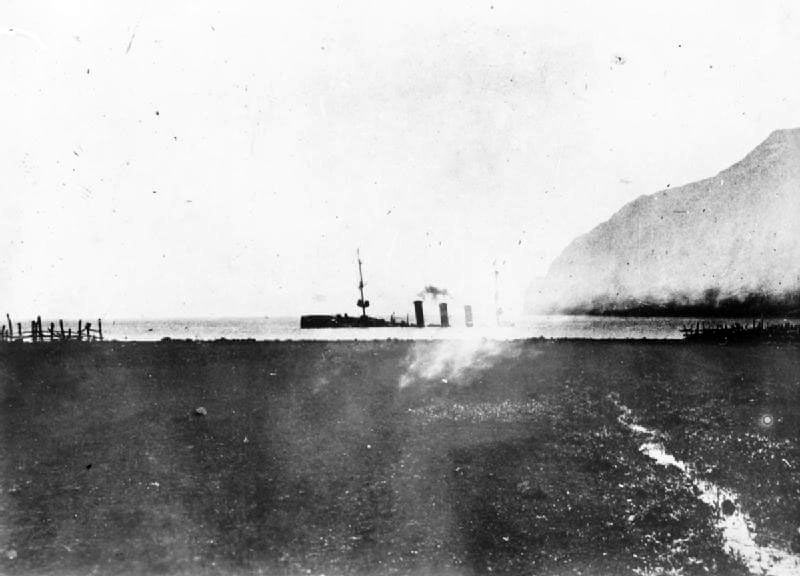

SMS Dresden, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914, immediately before the scuttling charges were exploded, sinking her on 14th March 1914 in the First World War

The Dresden passed round Cape Horn on 9th December and, after taking in coal, moved to Punta Arenas on 12th December to obtain more coal from a German ship. In early February 1915 Dresden left the islands of the southern tip of Chile and moved into the Pacific.

On 8th March 1915 in dense fog lookouts on Dresden saw the Kent. Both ships got up steam and a five hour chase ensued in which Dresden got away. Kapitän Lüdecke, the captain of Dresden, decided that the chase had rendered his engines incapable of further operation and his stocks of coal were nearly finished. Lüdecke took Dresden to the Island of Mas-a-fuera where he intended that the Chilean authorities would intern the ship.

On 14th March 1915 Kent and Glasgow found the Dresden in Mas-a-fuera and, in spite of the objections of the Chilean authorities, opened fire on her. Lüdecke sent one of his officers to negotiate with the British and point out that the ship had effectively been interned by the Chileans. Captain Luce of Glasgow simply informed the officer that his orders were to sink the Dresden. The German officer returned to find that Dresden was about to be scuttled. The crew were taken off and explosive charges set off which sank the Dresden. The crew was interned by the Chilean authorities.

SMS Dresden, German light cruiser at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914, sinking on 14th March 1915 in the First World War

Casualties at the Battle of the Falkland Islands:

HMS Invincible: no casualties.

HMS Inflexible: no casualties.

HMS Kent: 4 killed and 12 wounded.

HMS Cornwall: no casualties.

HMS Carnarvon: no casualties.

HMS Glasgow: 1 killed and 4 wounded.

HMS Bristol: no casualties.

HMS Macedonia: no casualties.

HMS Canopus: no casualties.

German Imperial Navy:

SMS Scharnhorst: no survivors of her crew of 52 officers and 788 non-commissioned ranks, including Admiral von Spee.

SMS Gneisenau: around 125 survivors of her crew of 38 officers and 726 non-commissioned ranks (598 men were lost with the ship).

SMS Dresden: no casualties.

SMS Nürnberg: 7 survivors of her crew of 14 officers and 308 non-commissioned ranks.

SMS Leipzig: 5 officers and 13 seamen survived of her crew of 14 officers and 280 non-commissioned ranks.

All the survivors from the German ships sunk became prisoners. The crew of the Dresden was interned by the Chilean authorities on 14th March 1915.

Decorations and medals for the Battle of the Falkland Islands:

Sergeant Mayes Royal Marine Artillery of HMS Kent awarded Conspicuous Gallantry Medal for his conduct at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

Sergeant Mayes, Royal Marine Artillery, on HMS Kent received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. The citation stated: ‘A shell burst and ignited some cordite charges in the casemate; a flash of flame went down the hoist into the ammunition passage. Sergeant Mayes picked up a charge of cordite and threw it away. He then got hold of a fire hose and flooded the compartment, extinguishing the fire in some empty shell bags which were burning. The extinction of this fire saved a disaster which might have led to the loss of the ship.’

Admiral Sturdee in his report to the Admiralty on the battle commended five officers from HMS Invincible, including the commander and Lieutenant Commander Dannreuther, the gunnery officer, but none from HMS Inflexible. From the other ships he commended three officers from HMS Kent and one each from HMS Glasgow and Cornwall.

Captain Luce of HMS Glasgow was made Companion of the Bath.

The Distinguished Service Cross was awarded to one officer from each of HMS Invincible, Kent and Cornwall.

Mrs Muriel Felton, a resident of the Falkland Islands, who spotted the German colliers and reported them to the Royal Navy, enabling them to be intercepted and sunk, was awarded an OBE.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of the Falkland Islands:

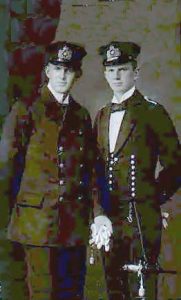

Leutnant Graf Otto von Spee of SMS Nürnberg and Leutnant Graf Heinrich von Spee of SMS Gneisenau, sons of Admiral Graf von Spee, both lost in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

• Corbett surmises that towards the end of the battle von Spee intended to disadvantage the two British battle cruisers by closing the range and bringing his secondary armament of 6 inch guns into action. Corbett says that von Spee will have been aware that Invincible and Inflexible had no secondary armament. It is clear that the two British ships were equipped with 4 inch guns. GF describes these guns being exercised during the journey south in November 1914.

• During Admiral Sturdee’s journey across the Atlantic with the British battle cruisers, HMS Invincible and Inflexible, a report appeared in the American press, in spite of the secrecy surrounding the despatch of the two ships. Von Spee was aware of the story, which related to the Invincible, but knew nothing further of where the ship was heading. It was reasonable to assume that Invincible’s destination was New York, to supervise the blockade of the German ships. The discovery by Gneisenau of the two battle cruisers in Port Stanley was a shock for von Spee and confirmed his conviction that the wanderings of his squadron were destined to end in its destruction and his death.

• There is something of a controversy over why von Spee’s squadron went to the Falkland Islands, when there was a reasonable chance they would encounter powerful British resistance, either naval or shore based. The surviving ships from Cradock’s squadron were likely to have returned to Port Stanley and included HMS Canopus, a battleship with 12 inch guns, although an elderly warship. Von Spee suspected that Cradock was supported by a battleship, although he did not know its identity. Corbett states that survivors from SMS Gneisenau informed the British that von Spee was persuaded to carry out the raid on the Falklands by the captain of the Gneisenau against von Spee’s own inclination. Interestingly the German naval spy von Rintelen claimed after the war that he was told by Admiral William Hall, Director of British Naval Intelligence, that the British used a broken German naval code to order von Spee to attack the Falklands Island radio station. The problems with this claim are numerous: Why did the Admiralty not inform Sturdee of this ruse as it could only work if his ships were in the Falklands when von Spee arrived? There was very limited direct radio communication, if any, between London and its own ships let alone with von Spee. There is no indication from the conduct of operations in the Pacific and Atlantic that the British Admiralty had access to German naval codes. It seems inconceivable that a British admiral would discuss secret naval matters with anyone, let alone a notorious German saboteur like von Rintelen, whom the British would have shot if they could have laid their hands on him.

Medal struck in Germany commemorating the deaths of the three Grafen von Spee at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

• Admiral Graf von Spee’s two sons, Otto and Heinrich, served in the East Asiatic Squadron under their father’s command, Otto in SMS Nürnberg and Heinrich in SMS Gneisenau. Both died in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914. A medal was issued in Germany commemorating the deaths of the father and his two sons.

German postcard showing the ‘last man’ about to go down on the upturned hull of SMS Nürnberg, sunk in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914 in the First World War

• The Battle of the Falklands was used extensively in Britain as a propanda tool.

British postcard showing the sinking of SMS Dresden on 15th March 1915 at Mas-a-fuera off Chile in the First World War: in fact the Dresden was scuttled by her crew

• After the action with SMS Dresden on 15th March 1915 at Mas-a-fuera and the scuttling of Dresden, a sailor from HMS Glasgow saw a pig struggling in the sea. With considerable difficulty the sailor rescued the pig, which was adopted as the mascot of HMS Glasgow and given the name ‘Tirpitz’ (after the German naval commander-in-chief). After a year Tirpitz was transferred to the Naval Gunnery School at Whale Island in Portsmouth, where he spent the rest of his life.

• HMS Canopus took part in the operations in the Dardanelles in 1915, providing gun fire support to the army onshore.

• The Kreigsmarine of the German Third Reich named one of their new pocket battleships (armoured cruisers) ‘Graf Spee’, laid down in 1932. The Graf Spee was scuttled on 18th December 1939 after an action with the Royal Navy cruisers HMS Exeter, Ajax and Achilles in the River Plate off Uruguay, not far from the Falkland Islands, where Admiral Graf von Spee was killed in action on 8th December 1914.

Lieutenant Commander Dannreuther first lieutenant and gunnery officer on HMS Invincible at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8th December 1914. Dannreuther was one of the six survivors when Invincible was sunk at Jutland on 31st May 1916 in the First World War

• The officer from SMS Dresden who went to negotiate with Captain Luce at Mas-a-fuera on 14th March 1915 was Oberleutnant zur See Wilhelm Canaris. Canaris escaped from internment in Chile and returned to Germany. In the Second World War as an admiral Canaris commanded the Abwehr, Germany’s military intelligence service. Canaris was executed by the Nazis for conspiring against Hitler.

• Admiral Sturdee was created a baronet for his services in the Battle of the Falklands, subsequently becoming admiral of the fleet.

• The battle cruiser HMS Invincible had an eventful and tragic career in the Great War. She was one of the battle cruisers at the Battle of Heligoland Bight. After the Battle of the Falkland Islands Invincible returned to the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow. At the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 the Invincible received a shell in one of her magazines and blew up with only 6 survivors. Lost with Invincible was the commander of the Third Battle Cruiser Squadron, Rear Admiral Hood. A battle cruiser was built and commissioned in 1920, named ‘Hood’ after the admiral’s 18th Century ancestor. HMS Hood received a hit in one of her magazines from the German battleship Bismark in the Denmark Strait on 24th May 1941 and blew up, much as Invincible blew up at Jutland, with only three survivors. The Battle in Denmark Strait was almost exactly 25 years after Jutland. HMS Defence was also lost at Jutland.

HMS Invincible exploding at the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 in the First World War. Only 6 of the crew survived, including Lieutenant Commander Dannreuther

•Assistant Paymaster Gordon Findlay of HMS Invincible wrote a novel based closely on his experiences in the ship, ‘A Naval Digression’, under the name ‘GF’ (quoted above). Findlay was still serving in Invincible at the time of Jutland, but was on leave when the Grand Fleet took to sea to meet the German High Seas Fleet on 31st May 1916 and Invincible was sunk with six survivors. C.S.Forester when researching the Royal Navy in the Second World War was told by an old Kent hand that during the pursuit of Nürnberg every hand who could be spared from his duties was sent aft to help lift the bows and increase speed (see ‘The Ship’ Penguin Books 1949 page 125).

• Paymaster Sub-Lieutenant Duckworth RN, whose photographs appear above, was an officer on HMS Invincible. He appears to be referred to in Gordon Findlay’s book ‘A Naval Digression by GF’ as owning the camera jointly with the ship’s surgeon. The arrangement appeared to be common in the Royal Navy during the Great War, photographs taken being sold to the newspapers. When the ship was in action the surgeon’s duties would have kept him below. A member of the pay staff, having no battle role, would be able to go on deck and take photographs, for some of Duckworth’s shots from the mast, presumably hence the partnership.

• A second Scharnhorst was built for the Kreigsmarine in the 1930s. This Scharnhorst was sunk by a British Fleet on 26th December 1943 off the northern Norwegian coast.

German ship ‘Scharnhorst sinking’ in the Second World War: Battleship Scharnhorst built for the Third Reich in the 1930s, sunk by a British Fleet on 26th December 1943 in the Battle of the North Cape off the coast of Northern Norway in the Second World War: picture by C.E. Turner

References for the Battle of the Falkland Islands:

• Naval Operations in the Great War Volume 1 by Sir Julian Corbett

• Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War 1

• Times History of the Great War Volume 2

• A Naval Digression by GF

The previous battle in the First World War is the Battle of Coronel

The next battle in the First World War is the Battle of the Dogger Bank