The Battle of Antietam or Sharpsburg, fought on 17th September 1862 and considered to be a Federal victory, bringing the Confederate 1862 invasion of Maryland to an end and giving President Lincoln and the Federal Congress the opportunity to issue the proclamation emancipating slaves throughout the United States of America, both North and South

The previous battle in the British Battle sequence is the Battle of Shiloh

The next battle in the American Civil War is the Battle of Fredericksburg

To the American Civil War Index

Name: The Battle of the Antietam or the Battle of Sharpsburg

Date of the Battle of Antietam: 17th September 1862

Place of the Battle of Antietam: At Sharpsburg in Western Maryland on the banks of the Potomac River.

Generals at the Battle of Antietam: Major General George B. McClellan commanded the Federal Army. General Robert E. Lee commanded the Confederate Army.

Numbers involved in the Battle of Antietam: The Federal Army comprised 87,164 troops with 275 guns. The Confederate Army comprised 41,000 troops with 194 guns.

Arms and equipment at the Battle of Antietam: Both sides suffered from significant difficulties in conducting land warfare in the 1860s. Small arms, with the Minie style of rifled musket, had become significantly more lethal than with the old short ranged, grossly inaccurate, smooth bore muskets that had been the standard infantry weapon for nearly 2 centuries. Rifled guns firing shell projectiles increased the range and effectiveness of artillery. More sophisticated systems of transport and organisation of supply, made possible by railroads and advances in industrial production, allowed for much larger armies. Tactics had advanced little from the era of the Napoleonic Wars of the beginning of the 19th Century in Europe. Probably only the Prussian army with its long standing General Staff had conducted sufficient study of the impact of changes in warfare to enable it to train its staff officers and generals to control the substantially greater and more sophisticated armies of the period. The French and British had first shown their failure to grasp the problems of warfare in the second half of the 19th Century during the Crimean War. The French confirmed this failure in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the British in the South African War of 1900. In each of these wars reliance was placed on successful colonial commanders with reputations made in small scale native wars who had little idea how to handle the large armies involved in a major war.

Uniforms: In Europe the French military establishment of Emperor Napoleon III was in the ascendancy, following the Crimean War and the wars in Northern Italy fought by the French against the Austrians. Both Federal and Confederate armies adopted French uniforms and in particular the French style ‘kepi’ and several regiments on each side adopted the uniforms of the French North African ‘Zouaves’. The Federal regiments wore dark blue. The Confederates in theory wore a light grey uniform. In practice the Confederate government was unable to maintain a proper supply of uniform clothing for its troops who wore whatever they could get their hands on. In many instances the readiest supply of uniforms lay in captured Federal supplies, leading to confusion on several battlefields, when Confederate troops were mistake for Federals.

Small arms: The Crimean War between the British and the French and the Russians from 1854 to 1856 saw the conversion of the British and French infantry from the old smoothbore musket, which had been in service for 150 years, to the Minié rifled musket, with its substantially increased range and accuracy. The Federal government equipped its infantry with Minié style rifled muskets bought initially from Europe, but increasingly manufactured in Federal armouries. Lacking a manufacturing base and cut off from European import by the Federal blockade, the Confederate government was forced to equip its soldiers with stocks of weapons seized from Federal armouries located in southern states. These were largely the old smooth bore muskets of short range and notoriously inaccurate. Many Confederate troops, without even these weapons, were forced to use whatever firearms they were able to bring on enlistment. As General Lee’s army captured Federal stocks established after the outbreak of war more modern firearms were seized and used to equip his infantry.

Artillery: As with small arms, the Northern access to European markets and its own manufacturing base gave the Federal army an immense advantage in the production of cannon. Broadly the Federal artillery was equipped with rifled guns firing shells, while the Confederate artillery was equipped with the old style smooth bore cannon, of lesser range and accuracy, firing ball, grape shot and case shot.

The Armies: The opposing armies at Antietam /Sharpsburg were in many ways compete contrasts. The Confederate army was a small homogenous force of highly experienced soldiers commanded by senior officers who fought as a team, providing support to each other without necessarily waiting for orders to do so. The Confederate artillery had been recently re-organised by Colonel Pendleton and was effective. The Federal army was much larger but comprised a high proportion of newly enlisted and wholly inexperienced regiments. In every area the Federal troops benefited from a generous supply of equipment. The Confederate troops that invaded Maryland were near to destitute. Many were barefooted. Uniforms were threadbare and in many instances replaced with captured Union clothing.

Orders of battle at the Battle of Antietam:

The Federal ‘Army of the Potomac’:

Commander: Major General George B. McClellan

I Corps commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker

Brigadier General Rufus King’s division: brigades of Doubleday, Patrick and Gibbon.

Brigadier General James B. Ricketts’ division: brigades of Duryée, Christian and Hartsuff.

Major General George G. Meade’s division: brigades of Seymour and Gallagher.

40 guns.

II Corps commanded by Major General Edwin V. Sumner

Major General Israel B. Richardson’s division: brigades of Caldwell, Meagher and Brooke.

Major General John Sedgwick’s division: brigades of Gorman, Howard and Dana.

Brigadier General William H. French’s division: brigades of Kimball, Morris and Webber.

42 guns.

V Corps commanded by Major General Fitz John Porter:

Major General George W. Morell’s division: brigades of Barnes, Griffin and Stockton.

Brigadier General George Sykes’ division: brigades of Buchanan, Lovell and Warren.

Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphrey’s division: brigades of Tyler and Allabach.

70 guns.

VI Corps commanded by Major General William B. Franklin:

Major General Henry W. Slocum’s division: brigades of Torbert, Bartlett and Newton.

Major General Darius N. Couch’s division (from IV Corps): brigades of Devens, Howe and Cochran.

36 guns.

IX Corps commanded by Major General Ambrose E. Burnside:

Brigadier General Orlando B. Willcox’s division: brigades of Christ and Welsh.

Brigadier General Samuel D. Sturgis’ division: brigades of Nagle and Ferrero.

Brigadier General. Isaac P. Rodman’s division: brigades of Fairchild and Harland.

Kanawha Division of Brigadier Jacob C. Cox: brigades of Ewing and Crook.

35 guns.

XII Corps commanded by Major General Joseph K. Mansfield:

Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams’ division: brigades of Crawford and Gordon.

Brigadier General George C. Greene’s division: brigades of Tyndale, Stainrock and Goodrich.

Cavalry Division of Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton: brigades of Whiting, Farnsworth, Rush, McReynolds and Davis.

36 guns.

Cavalry Division of Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton

16 guns.

The Confederate ‘Army of North Virginia’ commanded by General Robert E. Lee:

First Corps commanded by Lieutenant General James Longstreet:

Major General Lafayette McLaws’ division: brigades of Kershaw, Cobb, Semmes and Barksdale.

Major General Richard H. Anderson’s division: brigades of Cumming, Parham, Posey, Armistead, Pryor and Wright.

Major General John Bell Hood’s division: brigades of Wofford and Law.

Brigade of Brigadier General Nathan “Shanks” Evans.

Second Corps commanded by Lieutenant General Thomas J. Jackson

Major General D.H. Hill’s division: brigades of Ripley, Rodes, Garland, Anderson and Colquitt.

Major General A.P. Hill’s “Light Division”: brigades of Branch, Maxcey Gregg, Archer, Pender, Brockenbrough and Thomas.

Brigadier General John R. Jones’ division: brigades of Grigsby, Warren, Johnson and Starke.

Brigadier General Alexander R. Lawton’s division: brigades of Douglass, Early, Walker and Hays.

Reserve artillery commanded by Brigadier General William N. Pendleton

Cavalry Division commanded by Major General J.E.B. Stuart

Background to the Battle of Antietam: Following his campaign in the Peninsular and his unsuccessful advance on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, in the early summer of 1862, General McClellan withdrew his Federal army by sea and up the Potomac River to the area of Washington DC to combine it with the Federal Army of Northern Virginia commanded by General Pope. Familiar with the indecision in General McClellan’s character, the Confederate Commander in Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, counted on being able to defeat General Pope’s army before the combination of the two Federal armies could take place. General Lee defeated General Pope at the Second Battle of Bull Run (or Second Battle of Manassas). Pope’s army retreated in reasonably good order to the Potomac River and General McClellan assumed command of the combined armies. General Lee then embarked on an invasion of Western Maryland. Several reasons are given for the invasion. Maryland was known to harbour many Confederate sympathisers and it was hoped that the arrival of the Confederate army would bring in significant numbers of recruits. The Confederacy needed to achieve international recognition for its independent status. It was hoped that a victory on Federal soil would cause Britain and France to concede that recognition. It was hoped to bring pressure to bear on the Northern Electorate in the upcoming elections by carrying the war to the North, thereby encouraging the large northern peace movement.

The invasion was not a particular success, except for the capture of the Federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry with 10,000 prisoners and a substantial quantity of supplies. Few additional Marylanders joined the Confederate army.

General McClellan closed moved against the Confederate army from Washington DC with a significantly larger army. As he did so the Confederate army lay divided with General Jackson’s corps at Harper’s Ferry dealing with the Federal capitulation and General Longstreet’s corps at Hagerstown to the North. General Lee was at Sharpsburg with only 12,000 men.

McClellan had notice of the wide distribution of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia through the discovery of a copy of one of General Lee’s orders that gave these details (see below). McClellan failed to act with expedition to take advantage of this information continuing his slow advance. Withdrawing from Hagerstown the Confederates were able to delay the Federal advance at the battles of Crampton Gap and South Mountain on 14th September 1862.

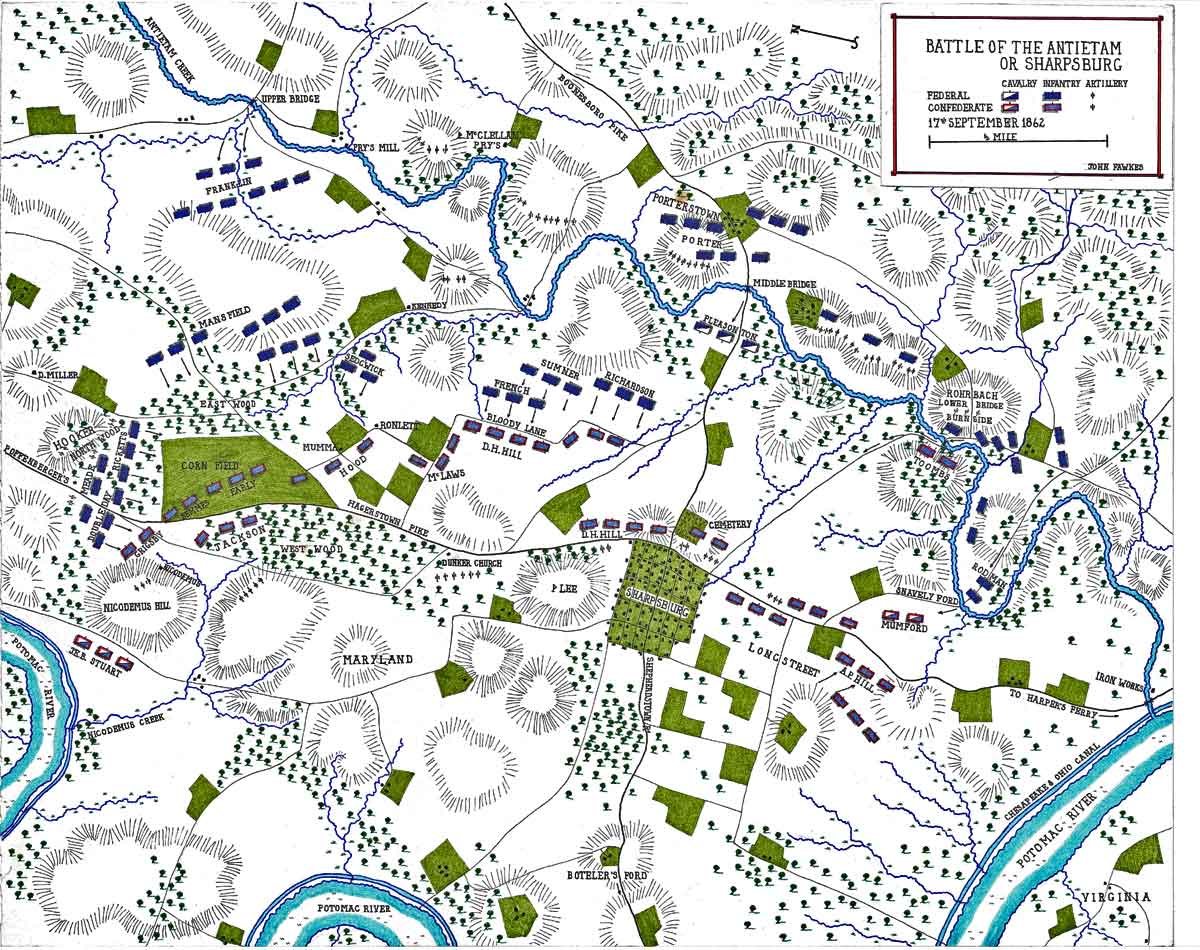

Map of the Battle of the Antietam fought on 17th September 1862 in the American Civil War: map by John Fawkes

Account of the Battle of Antietam: By 16th September 1862 General Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had concentrated, less A. P. Hill’s “Light Division” which was hurrying up from Harper’s Ford, in positions around the Maryland town of Sharpsburg between the Potomac River, that marked the boundary between the North (Maryland) and the South (Virginia), and Antietam Creek that flowed on a North-West to South-East course joining the Potomac south east of Sharpsburg. The Confederates occupied the rising ground North West of the town and additional rising ground to the East.

The Antietam Creek varied between around 50 to 100 feet in width and was fordable in several places although the banks were high making it difficult for bodies of troops to access the fords. Roads crossed the creek by bridge in 4 places in the proximity of Sharpsburg: The Upper Bridge on the Confederate left wing, the Middle Bridge opposite the Confederate centre on the Boonsboro Pike, the Lower or Rohrbach Bridge immediately before the Confederate right and the Antietam Bridge at the point where the Creek flowed into the Potomac. While the Upper and Middle Bridges were a mile or so from the Confederate positions, 2 Confederate brigades occupied hills immediately overlooking the Lower Bridge. The Antietam Bridge played no part in the battle other than as the point of crossing for A.P. Hill’s division as it hurried up from Harper’s Ferry to reinforce the Confederate Right Wing (although many accounts have A.P. Hill marching along the Virginia bank of the Potomac and crossing by Boteler’s Ford.

General McClellan’s plan for his Federal Army was to launch attacks on each flank of the Confederate position, crossing by the Upper and Lower Bridges. While constrained by his constitutional aversion to risk and his persistent overestimating of Confederate strength, McClellan was, no doubt, concerned at the high proportion of newly recruited regiments in the Federal army as against the known experience and effectiveness of his opponent’s troops.

It must have been apparent that General Lee hoped to inflict significant casualties on the Federal army by giving battle from a defensive position.

The battle developed during the course of 17th September 1862 beginning with the attack by General Hooker’s 1st Corps on General Jackson’s positions on the Confederate Left in the early morning, the attack on the Confederate Centre at the end of the morning and the final assault by General Burnside across the Lower Bridge towards Sharpsburg in the late morning and afternoon. Throughout the battle General Porter’s V Corps remained in reserve, in the centre of the Federal position and behind the Antietam Creek.

The consequence of the lack of co-ordination of the Federal attacks was that General Lee was enabled to reinforce the section of his line that was under attack with troops from the other sections.

The broad timings of the attacks were:

17th September 1862:

5pm Hooker’s Federal I Corps crosses Antietam Creek by the Upper Bridge and briefly engages Confederate forces around the North Wood. I Corps camps overnight around the North Wood.

18th September 1862:

5.30am Hooker’s Federal I Corps begins the battle with its attack down the Hagerstown Pike towards Sharpsburg against General Jackson holding the Confederate Left Flank.

7am Hood’s Confederate counter attack drives Hooker’s corps back up the Hagerstown Pike.

7.30am Sumner’s Federal II Corps begins its assault on the East Wood in support of Hooker and is driven back.

9.30am French’s Federal Division begins its assault on Confederate positions around Bloody Lane in the Confederate Centre.

10am McClellan orders Burnside’s Federal IX Corps to begin its attack across the Antietam at the Lower Bridge against the Confederate Right Flank. First Federal assault on the bridge driven back.

10.30am Richardson’s Federal Division attacks the Confederate positions around Bloody Lane. Confederate positions are further reinforced.

12 midday Burnside’s Federal IX Corps launches its second unsuccessful assault on the Lower Bridge in the face of fierce opposition. Rodman’s Federal Division attempts to ford the creek further downstream.

1pm McClellan orders Franklin not to attack in the area of the Bloody Lane with his Federal VI Corps. Fighting around Bloody Lane comes to a halt.

12.30pm Burnside’s Federal IX Corps launches its third assault on the Lower Bridge. Toomb’s Confederate Brigade, defending the bridge, withdraws leaving Burnside’s corps in possession of the Lower Bridge.

2.30pm AP Hill’s Confederate Light Division arrives from Harper’s Ferry.

3pm Burnside’s Federal IX Corps presses across the Lower Bridge and Snavely’s Ford and advances on Sharpsburg against weakening Confederate resistance.

3.40pm AP Hill’s Confederate Division counter-attacks Burnside’s Federal IX Corps to the South of Sharpsburg. Burnside abandons his attack and falls back to the Lower Bridge to await reinforcement by McClellan. McClellan declines to reinforce him.

5.30pm Battle finishes: Federals; Hooker back in North Wood, Sumner between Bloody Lane and Antietam Creek, Porter still east of Antietam Creek and Burnside back at Lower Bridge. Confederates: occupying the positions they had held at the beginning of the day to the North and South of Sharpsburg except at the Lower Bridge.

18th September 1862; in the evening, General Lee withdraws his Confederate Army across the Potomac River into Virginia ending his 1862 invasion of Maryland.

The course of the Battle of Antietam:

General Hooker with his I Corps of the attacking Federal army had the least difficulty crossing the Antietam, using the Upper Bridge, which was well away from the Confederate positions and not under artillery fire. I Corps was in place around Poffenburger’s Farm on the night of 16th September 1862, with fighting taking place on that evening, and began its attack on the Confederate left flank first thing in the morning of 17th September.

In order to counter Hooker’s I Corps’ attack General Lee brought Confederate brigades to his left flank, commanded by General Jackson, causing an intermingling of brigades from each of his two corps.

The line of Hooker’s advance was down the Hagerstown Pike towards Sharpsburg. His troops soon encountered a large field on the east side of the road, containing a standing crop of corn. His three divisions took the field against strong Confederate resistance, both infantry and artillery, but were driven back. For the rest of the morning the fighting comprised the taking and re-taking of the ‘Corn Field’ by Hooker’s corps and by Mansfield’s supporting XII Corps, against repeated and determined Confederate counter-attacks launched under the aggressive direction of General ‘Stonewall’ Jackson.

Artillery support for the Confederate infantry was provided by the horse artillery batteries of General Stuart’s cavalry division from Nicodemus Hill, behind the Confederate left flank, and by Confederate field artillery on raised ground towards the Dunker Church. Federal guns supported their infantry from positions further up the Hagerstown Pike and on the east bank of the Antietam Creek.

By the end of the morning Hooker’s I Corps had been fought to a standstill and was back at the north end of the ‘Corn Field’.

The axis for the Federal attack on General Lee’s position shifted to his centre as divisions from General Sumner’s II Corps came up on Hooker’s left. Here a network of rural lanes, sunken by years of farm traffic and lined by wooden railings, provided the Confederate troops with the anchors for their line. As in many battles in the War such positions enabled defending infantry to inflict significant casualties on troops advancing across country to attack them. The key part of this position came to be known as the ‘Bloody Lane’.

Sumner’s Corps attacked the Confederate positions, suffering heavy loss, but managed to make some penetration. The fighting was fierce but the lack of pressure on the Confederate right enabled Lee to commit sufficient reinforcement s to drive back the Federal attack.

Towards the middle of the day Burnside’s attack on the Confederate right began to develop. Burnside’s Federal II Corp had the role of crossing the Lower or Rohrbach Bridge and advancing on Sharpsburg. This was the only section of the Confederate line where it Lee’s dispositions directly resisted the Federal crossing of the Antietam Creek. The Confederate brigade of Brigadier General Robert Toombs occupied the hilly ground overlooking the bridge. While only numbering around 600 men Toombs’ Georgian brigade was well placed to prevent an easy crossing of the bridge.

Burnside has been severely criticised for failing to press his attack with sufficient vigour and for failing to find alternative crossing points to the bridge. The attack on the bridge was made more difficult by the lay of the approach road along the east bank of the creek, directly under the fire of the Confederates positioned on the hill on the far bank.

General McClellan directed Burnside to begin his attack at some time between 9am and 10am. Burnside’s first attempt to cross the bridge was repelled with considerable casualties by the fire from Toombs’ men.

In the meantime General Rodman’s Federal division advanced into the loop of the creek downstream of the bridge to cross at Snavely’s ford in the rear of Toombs’ position.

At around midday Burnside launched his second attempt to cross the Rohrbach Bridge. Again, the assault was driven back by Toombs’ Georgian riflemen.

Aware that the attacks on the Confederate left and centre were foundering and that the Federal troops were in considerable danger in those parts of the battle field, McClellan was sending increasingly frenzied demands to Burnside to cross the bridge and attack towards Sharpsburg.

At around 3pm Burnside’s troops finally forced the bridge. By this time Rodman’s Federal troops were crossing the Antietam Creek by Snavely’s Ford and Toombs’ brigade was withdrawing towards Sharpsburg. Burnside’s Federal troops pressed towards Sharpsburg. The delay at the Lower Bridge (now to be called Burnside’s Bridge) had given time for A.P.Hill’s ‘Light Division’ to reach the battle field from Harper’s Ferry, coming up on the Confederate Left. These highly experienced and effective Confederate infantry at around 3.45pm launched an attack on Burnside’s flank, quickly overwhelming a number of newly recruited regiments and causing Burnside to fall back to the Lower Bridge, where he called for reinforcements from McClellan, a request which was not met. As in the other parts of the battlefield stalemate had been imposed.

McClellan still had significant numbers of uncommitted troops. Porter’s Federal V Corps still lay to the East of the Antietam Creek. Pleasonton’s cavalry division was to the West of the creek on the Boonesboro Pike and had taken little part in the battle. The Confederate Army had largely been fought to a standstill. Lee had virtually no reserves left. His casualties had been substantial and several key brigades had virtually ceased to exist as fighting entities. McClellan chose not to renew the attack and the battle ended.

On the next day, 18th September 1862, Lee and Jackson exhaustively examined the options for a counter-attack on the positions occupied by Hooker’s I Corps around the North Wood, but the Federals had heavily reinforced their positions with artillery and the Confederate artillery was not sufficiently strong to support such a counter-attack.

That night the Confederate army withdrew across the Potomac into Virginia by Boteler’s Ford and the 1862 incursion into Northern territory had ended.

Casualties: Out of 41,000 troops engaged the Confederates lost 9,500 killed and wounded. Generals Branch and Starke were killed. Out of 87,000 troops engaged (although around 21,000 took little part) the Federals lost 12,410 killed and wounded. Corps Commander General Mansfield and divisional commanders Generals Richardson and Rodman died of wounds. Corps Commander Hooker was wounded.

Aftermath: The Federal army attempted a limited follow up by crossing the Potomac River, but was repelled. The Confederate army fell back behind the line of the Rappahannock River, followed by the Federal army.

President Lincoln and the Federal authorities considered that General McClellan had been insufficiently decisive in failing to take advantage of his considerable advantage over General Lee in numbers of infantry and guns and in failing to exploit his limited victory. In due course they relieved General McClellan of his command of the Federal Army of the Potomac and replaced him by General Burnside.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Antietam:

- On 13th September 1862, when General McClellan was at Frederick in Maryland, he was brought a copy of General Lee’s written order directing the capture of Harper’s Ferry. The order gave the position of each of Lee’s divisions, showing that they were widely scattered, with Jackson’s 2nd Corps at Harper’s Ferry and Longstreet’s 1st Corps at Hagerstown. The order was found wrapped around 3 cigars lying in the street by 2 NCOs of the 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry, Corporal Mitchell and Sergeant Bloss. General McClellan expressed his satisfaction at receiving the order while standing in the public street in Frederick in the presence of Confederate sympathisers. As a result, General Lee was quickly informed of the incident. It is not clear who was responsible for the loss of the order. It had been written by General Lee’s adjutant general and is therefore likely to have been intended for one of his senior commanders. General McClellan is criticised for waiting 18 hours before acting on the information in the order, thereby giving General Lee the opportunity to concentrate his army for the battle.

- Major Leopold Blumenberg commanded the 5th Maryland Volunteer Infantry at the Antietam. Blumenberg had served as a regular officer in the Prussian Army, rising to the rank of First Lieutenant. Blumenberg found that prejudice against him as a Jewish officer made it unlikely that his career would progress much further in the Prussian service. He sent in his papers and emigrated to Maryland. After Antietam, Blumenberg served on the staff and after the War received an appointment from the Federal Government in the Customs Service.

The previous battle in the British Battle sequence is the Battle of Shiloh

The next battle in the American Civil War is the Battle of Fredericksburg

To the American Civil War Index

Designed and maintained by Chalfont Web Design

© Britishbattles.com 2002 – 2016;