The naval engagement on 24th June 1340 that marked the beginning of the Hundred Years War and established England in its succession of victories under Edward III

The previous battle in the British Battles series the Battle of Halidon Hill

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Morlaix

War: Hundred Years War

Date of the Battle of Sluys: 24th June 1340.

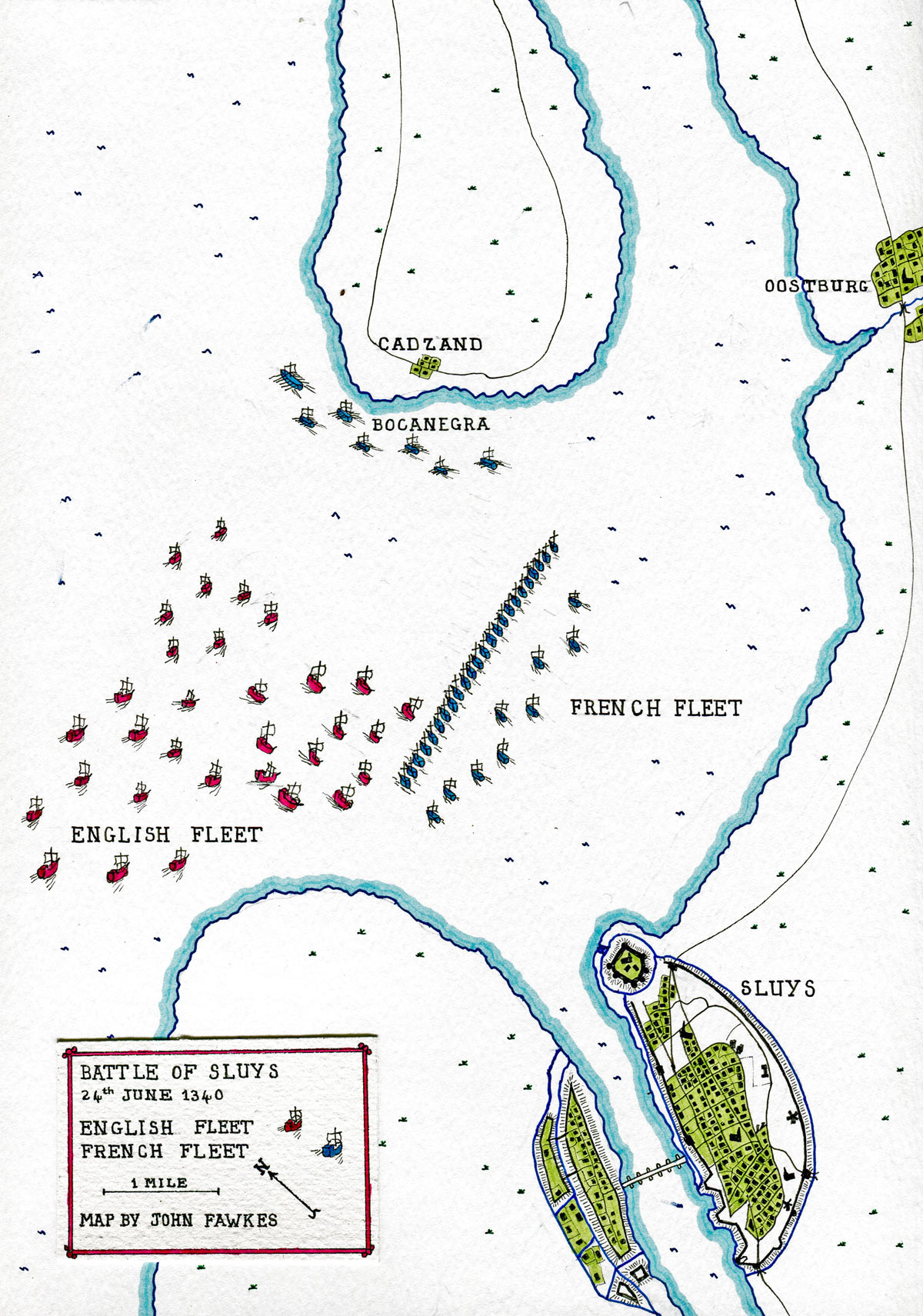

Place of the Battle of Sluys: The battle took place in and around the harbour of Sluys in an inlet on the border between Zeeland and West Flanders.

Due to silting and land reclamation Sluys or L’Écluse in French or Sluis in Dutch is now well inland; in the mid 14th Century Sluys was a great harbour able to take large numbers of ships.

Combatants at the Battle of Sluys: The English fleet against a combined French, Castilian and Genoese fleet.

Commanders at the Battle of Sluys: Edward III, King of England against the French commanders, Hugues Quiéret and Nicolas Béhuchet, with the Genoese Commander, Egidio Bocanegra.

Size of the navies: Figures for the navies vary widely among authorities: The English are said to have had up to 400 ships. The French fleet are said to have had some 250 ships. Other than a small number of large vessels such as the Christopher, the Edward and the Thomas, most of the ships were extremely small, carrying crews of sailors and fighting men of around 25.

Nicolas Béhuchet French Admiral captured and hanged after the Battle of Sluys on 24th June 1340 in the Hundred Years War

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Sluys: It seems likely that neither England nor France had a dedicated fleet of warships in the mid-14th Century. In times of war each king called upon the merchant vessels of his subjects and manned them, in addition to their crews, with archers and men-at-arms; converting the ships for war by building forecastles, after castles and crows nests, fortifications from which archers directed their fire onto enemy vessels.

These merchant vessels were called Cogs; square rigged and single masted with sharp prows and sterns and steered by an oar or a rudder.

The nearest to a formal English navy was the arrangement King Edward III had with the Kentish towns known as the Cinque Ports. In return for trading privileges the Cinque Ports provided a number of vessels for a period each year for royal military purposes.

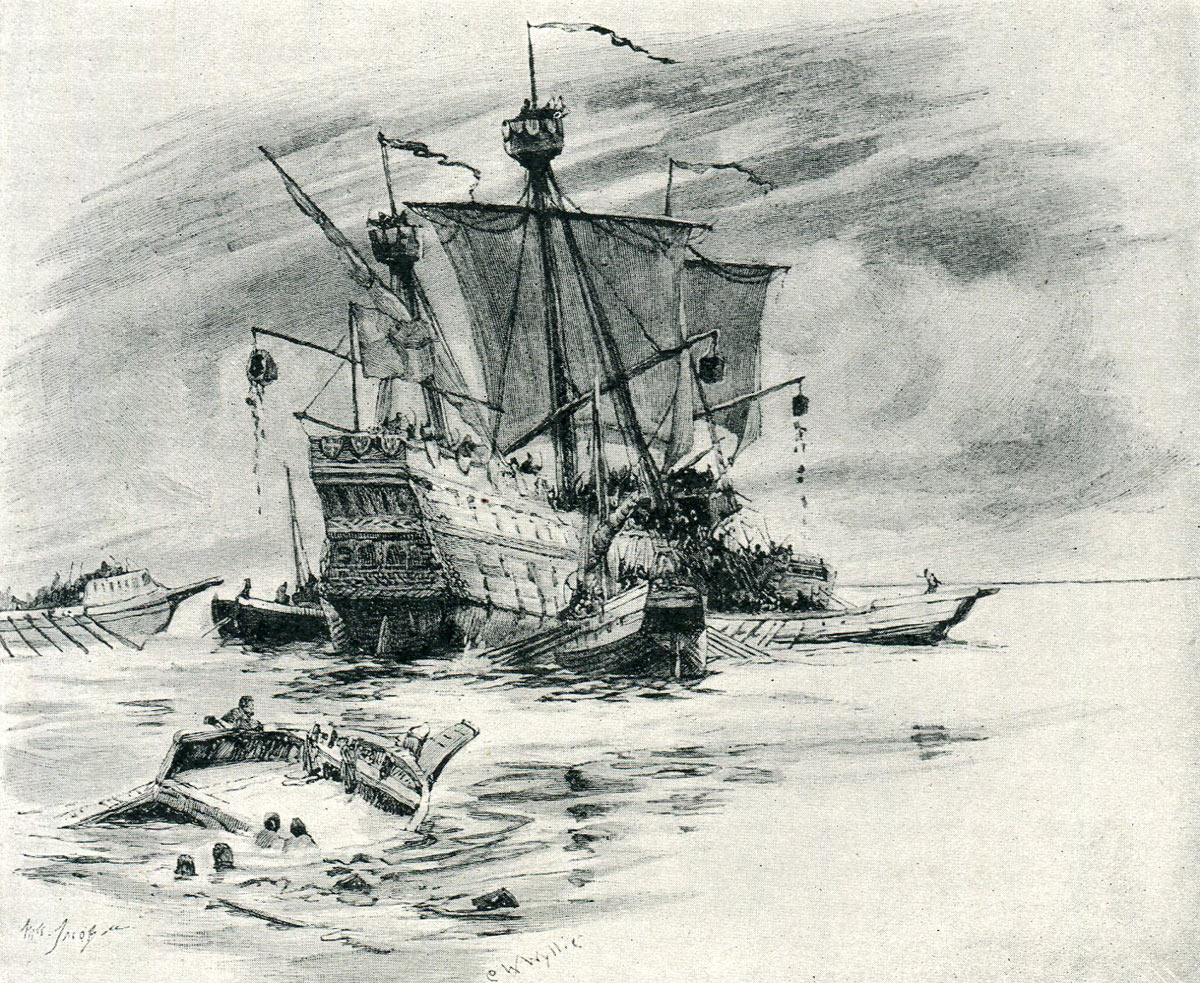

The capture of the English ship Christopher by the French in 1338: Battle of Sluys on 24th June 1340 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Lionel Wyllie

French ships were shallow drafted and small, highly manoeuvrable particularly in shallows, while the English ocean-going Cogs, larger and with a deeper draught, were slower to manoeuvre. The Genoese and Castilian fleets comprised galleys, powered by sail and oars, specifically constructed for war.

The English armed one or two of their vessels with guns, some of the larger ships at Sluys having two or three pieces of ordnance on board.

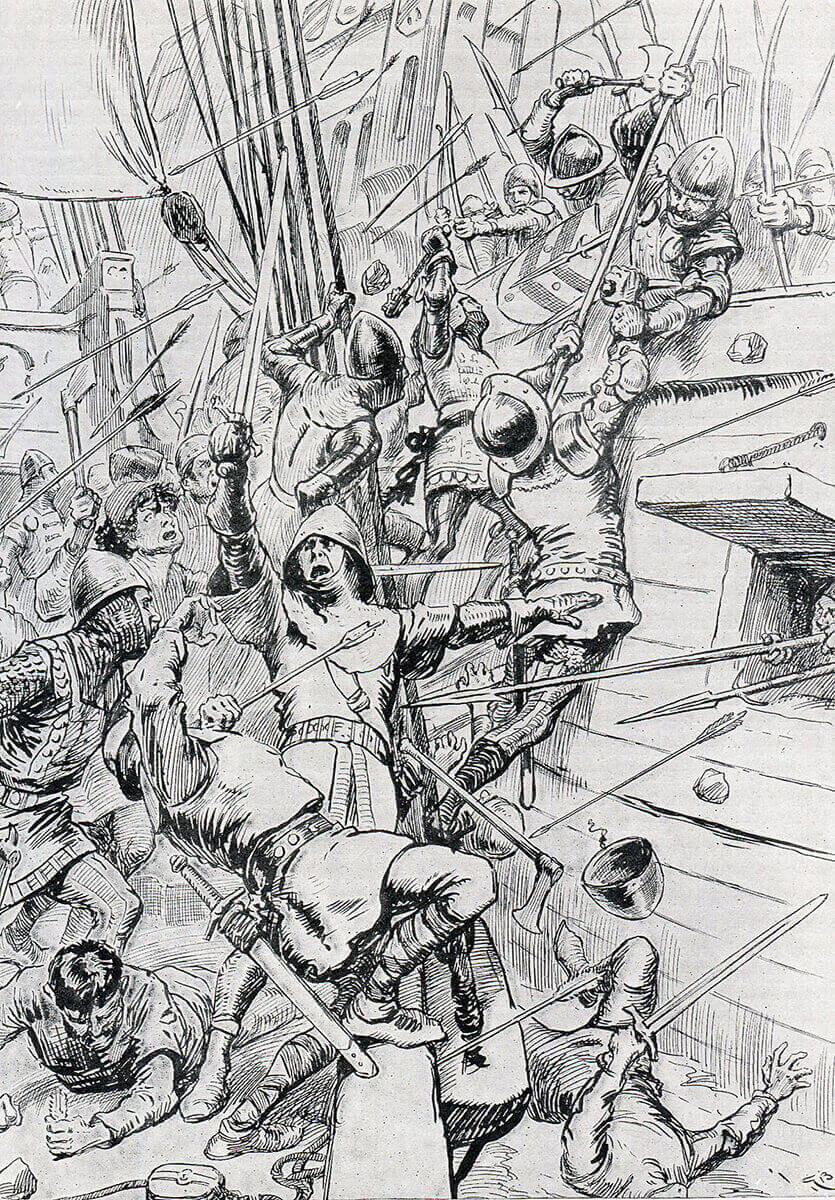

In battle a ship would lay alongside an enemy, decimate her crew with discharges of arrows and showers of heavy stones, leaving the way clear for men-at-arms to board overcome the survivors and take the ship and its crew. It seems to have been the practice of the time to throw captured enemy soldiers over the side unless they seemed sufficiently well equipped to be worth a ransom.

Winner of the Battle of Sluys: The English fleet of Edward III won the battle decisively.

Account of the Battle of Sluys: Edward III, King of England, began the Hundred Years War, claiming the throne of France on the death of King Philip IV in 1337. The war finally ended in the middle of the 15th Century with the eviction of the English from France, other than Calais, and the formal abandonment by the English monarchs of their claims to French territory.

The war at sea began badly for the English, a French flotilla capturing the Christopher and the Edward, believed to be among the largest vessels afloat, after a fierce struggle in the English Channel. Later the same year a French flotilla raided Plymouth, burning the town and capturing the shipping in the harbour.

In 1340 King Edward assembled a fleet for his assault on the coast of Northern France to enforce his claim to the throne of France and in support of Flemish resistance to the French.

To counter the English threat King Philip VI of France ordered the assembly of a large fleet in the Channel port of Sluys, then considered the best harbour in Europe (now silted up and forgotten), to be commanded by the admiral Hugues Quiéret and one of Philip’s civil servants the lawyer Nicolas Béhuchet.

An English Cog, possibly the Thomas on which King Edward III embarked before the Battle of Sluys on 24th June 1340 in the Hundred Years War

The French allies Castile and Genoa sent a force of galleys, commanded by the Genoese Bocanegra, to join the French fleet in Sluys.

Various English aristocrats and royal officials held the responsibility for assembling the merchant ships in the different parts of the country to form Edward’s fleet: Sir Robert Morley brought 50 ships from the North of England, the Earl of Arundel the merchant fleet from the West of England and the Earl of Huntingdon the shipping from the Cinque Ports in Kent.

King Edward embarked on the cog, Thomas, at Ipswich on 20th June 1340 and led his fleet across the Channel, being joined by Morley’s ships off Blankenberg on the Flanders’ coast. Edward’s fleet was now complete at perhaps 300 to 400 sail. The ships were small, most having a regular crew of 5 or 6, with an additional fighting force of 10 to 15 archers and men-at-arms.

Nearing the coast to the North East of Sluys an English ship put the veteran soldiers, Sir Robert Crawley and Sir John Crabbe, a Scotsman, ashore to reconnoiter the French fleet (other authorities state that the two knights were Sir Reginald Cobham and Sir John Chandos). The two knights rode to Sluys with a Flemish escort. On their return Crawley and Crabbe described the situation of the French fleet in the harbour and advised against attack, as too risky in such a confined space.

Edward flew into a rage and vowed to deliver his attack without delay.

The English fleet advanced on Sluys in battle formation of two lines. They found the French/Genoese/Castilian fleet had adopted the standard defensive formation used by fleets at sea. The French ships were in two lines within the harbour, the ships of each line bound together using boarding lines.

This technique was frequently used at sea to enable soldiers to move easily from ship to ship, countering boarding parties that attempted to take any part of the line. The disadvantage was that the ships were deprived of any freedom of manoeuvre.

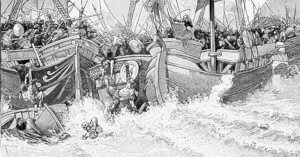

The Christopher together with other captured ships lay at the left hand end of the first French division. Eager to recapture the English vessels Sir Robert Morley led the attack on the left flank of the French fleet; his archers shooting down the crews, while the men-at-arms boarded and cleared the ships in a series of savage hand-to-hand combats, working their way down the French line taking ship after ship. Lashed together as they were, the ships of the leading division of the French fleet were unable to reinforce the point of danger.

The ships in the French second division cast off their lines, some joining the fight, others attempting to escape. Bocanegra took his galleys out to sea using their ability to row against the wind, drove back a pursuing force led by Crabbe and sailed off to the West, leaving the French to fend for themselves as best they could.

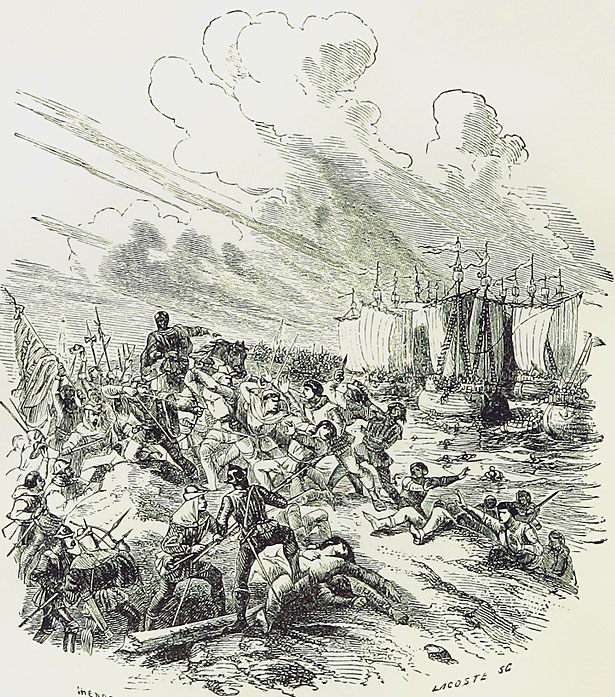

In the violent battle ships were taken, retaken and taken again until the French fleet was overwhelmed and destroyed. Knights, men-at-arms and ordinary soldiers and sailors jumped or were thrown into the sea, drowning under the weight of their armaments, or, if they made it to the shore, being clubbed to death by the vengeful Flemings.

English men-at-arms boarding a French ship at the Battle of Sluys on 24th June 1340 in the Hundred Years War

The battle ended at nightfall with an overwhelming English victory.

Casualties at the Battle of Sluys: As with all medieval battles casualties are hard to calculate with precision. Formal records for armies were not kept and there is no reliable mechanism for working out how many men attended in any particular army or navy. Froissart writes of a frightful slaughter. It seems likely that the casualties were in the tens of thousands. The French probably lost every ship other than Bocanegra’s galleys. Of the French commanders Hugues Quiéret was killed and Nicolas Béhuchet captured and hanged by Edward III.

Follow-up to the Battle of Sluys:

Sluys destroyed the French naval capability for some years and enabled King Edward III to land forces in Northern and Western France with little opposition.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Sluys:

- To demonstrate the sincerity of his claim to the French throne King Edward III quartered his coat of arms with the lilies of France. The lilies can be seen on the Royal Standard flying from the masthead of the ship on the left of the above illustration, probably Edward’s flagship, the Thomas.

- Many well known English knights were present at the battle including Sir Walter Manny (the victor of an earlier smaller battle at Sluys), Lord Wake and Lord Ferrers.

- Also present in the English fleet was Sir Guy of Flanders, commander of the garrison of Sluys in Manny’s 1337 assault on the town; after which he changed sides. Froissart describes Sir Guy as “a good sure knight, but a bastard”. This was probably a comment on his origins rather than his attitude to military discipline.

- King Edward III had with him the household of his Queen. One of the ladies of the household is said to have been killed in the battle.

- No member of the French court was prepared to give the French King Philip VI the terrible news of the destruction of his fleet at Sluys. Finally a court jester, traditionally enabled to be impertinent with impunity, said to King Philip VI, “Our knights are much braver than the English.” “How so?” said Philip. “The English do not dare to jump into the sea in full armour.”

- Sluys or L’Écluse in French or Sluis in Dutch lies in the south-west corner of the Netherlands and is now about ten miles inland its harbour filled in by silting and reclamation. Cadzand is no longer a coastal village and is about a mile from the sea shore. Oosterburg likewise lies some miles inland.

References for the Battle of Sluys:

The Hundred Years War by Alfred H. Burne.

Trial by Battle, Volume I of the four volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Hundred Years War by Robin Neillands.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle in the British Battles series the Battle of Halidon Hill

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Morlaix