King Edward III’s crushing English victory over the French on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War; the Black Prince winning his spurs and acquiring the emblem of the Three White Feathers

Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: Froissart’s magnificent representation more imaginative than accurate

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Caen

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Calais

English knights awaiting the French attack at the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War

King Edward III of England victor at the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War

War: Hundred Years War

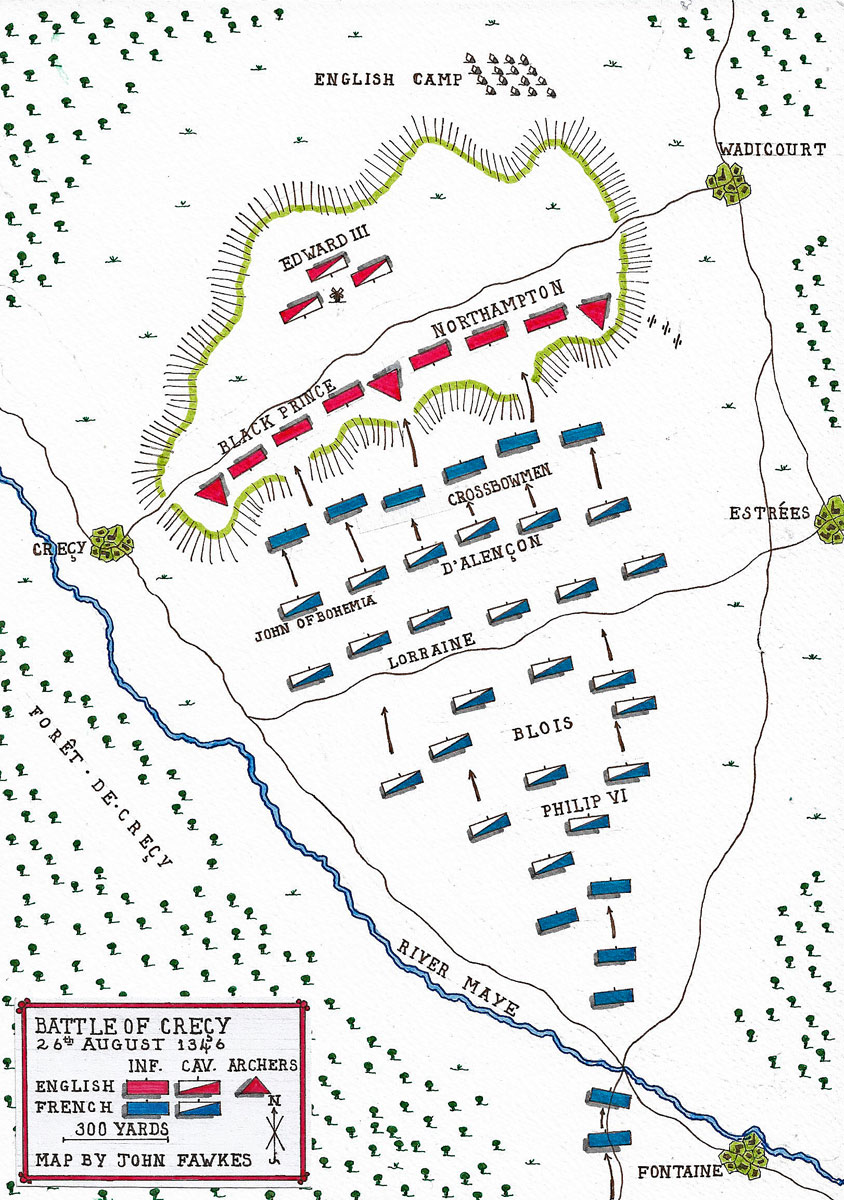

Date of the Battle of Creçy: 26th August 1346.

Place of the Battle of Creçy: Northern France.

Combatants at the Battle of Creçy: An English and Welsh army against an army of French, Bohemians, Flemings, Germans, Savoyards and Luxemburgers.

Commanders at the Battle of Creçy: King Edward III with his son, the Black Prince, against Philip VI, King of France.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Creçy: The English army numbered some 4,000 knights and men-at-arms, 7,000 Welsh and English archers and some 5,000 Welsh and Irish spearmen. The English army fielded 5 primitive cannon.

Numbers in the French army are uncertain but may have been as high as 80,000 including a force of some 6,000 Genoese crossbowmen.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Creçy: The power of the medieval feudal army lay in the charge of its mass of mounted knights. After the impact delivered with the lance, the battle broke into hand to hand combat executed with sword and shield, mace, short spear, dagger and war hammer.

Depending upon wealth and rank a mounted knight of wore jointed steel armour incorporating back and breast plates, a visored bascinet helmet and steel plated gauntlets with spikes on the back; the legs and feet protected by steel greaves and boots, called jambs. Weapons carried were a lance, shield, sword and dagger. Over the armour a knight wore a jupon or surcoat emblazoned with his arms and an ornate girdle.

The French King commanded a force of Genoese crossbowmen, their weapons firing a variety of missiles; iron bolts or stone and lead bullets, to a range of some 200 yards. The crossbow fired with a flat trajectory, its missile capable of penetrating armour.

The weapon of King Edward’s archers was a six foot yew bow discharging a feathered arrow a cloth metre in length. Arrows were fired with a high trajectory, descending on the approaching foe at an angle. The rate of fire was up to one arrow every 5 seconds against the crossbow’s rate of a shot every two minutes; the crossbow requiring to be reloaded by means of a winch. For close quarter fighting the archers used hammers or daggers to batter at an adversary’s armour or penetrate between the plates.

While a knight was largely protected from an arrow, unless it struck a joint in his armour, his horse was highly vulnerable, particularly in the head, neck or back.

The Welsh and Irish infantrymen, carrying spears and knives, made up a disorderly mob of little use during battle, being mainly concerned with ransacking the countryside and murdering the inhabitants or pillaging a battlefield once the combat was over. A knight or man-at-arms, knocked from his horse and pinned beneath its body, would be easily overcome by the swarms of these marauders.

The English army possessed simple artillery; improvements in the composition of black powder reducing the size of guns and projectiles and making them sufficiently mobile to be used in the field. It seems that the French had not by the time of Creçy acquired artillery.

Winner of the Battle of Creçy: The English army of Edward III won the battle decisively.

Account of the Battle of Creçy:

Edward III, King of England, began the Hundred Years War, claiming the throne of France on the death of King Philip IV in 1337. The war finally ended in the middle of the 15th Century with the eviction of the English from France, other than Calais, and the formal abandonment by the English monarchs of their claims to French territory.

The battlefield of Creçy showing the windmill at which King Edward III positioned himself and the English reserve at the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War

On 11th July 1346 Edward III, King of England, with an army of some 16,000 knights, men-at-arms, archers and foot soldiers landed at St Vaast on the peninsular of the Contentin on the north coast of France, intent on attacking Normandy, while a second English army landed in South Western France at Bordeaux to invade the province of Aquitaine. One of the King’s first actions on landing in France was to knight his 16 year old son Edward, Prince of Wales (known to posterity as the Black Prince).

Edward then marched south to Caen, the capital of Normandy, capturing the town and taking prisoner the Constable of France, Raoul, Count of Eu.

Marching on to the Seine, the English Army found the bridges across the river destroyed, whilst news came in of an enormous army gathering in Paris under the French King, Philip VI, bent on destroying the invaders.

Edward’s army was forced to march up the left bank of the Seine as far as Poissy, approaching perilously close to Paris, before a bridge could be found, damaged but sufficiently repairable to allow the army to cross the river.

Once over the Seine Edward marched north for the Channel coast, followed closely by King Philip.

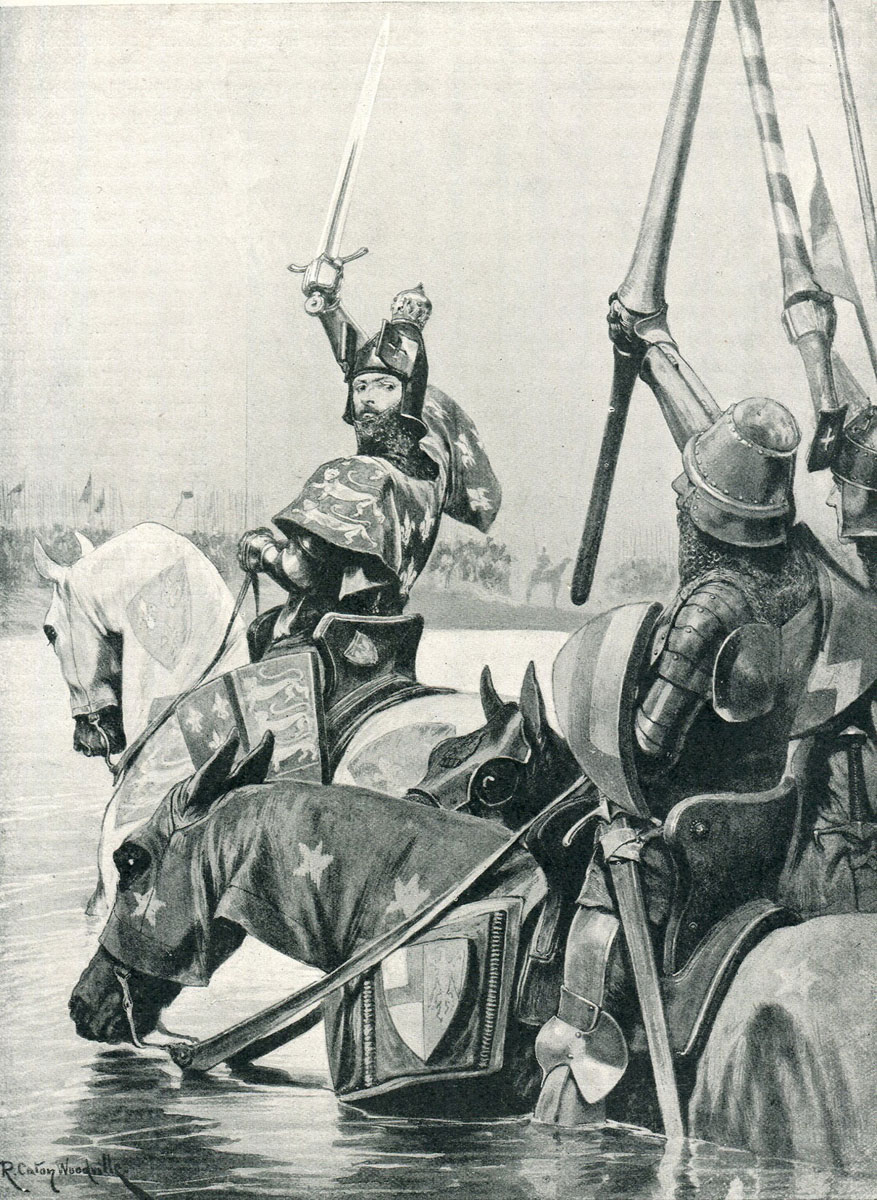

King Edward III crossing the River Somme before the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

As with the Seine, the English found the River Somme an impassable barrier, the bridges heavily defended or destroyed, forcing them to march down the left bank to the sea. They finally crossed at the mouth of the river at low tide, just evading the clutches of the pursuing French. Exhausted and soaked Edward’s troops encamped in the Forêt de Creçy on the north bank of the Somme.

On 26th August 1346, in anticipation of the French attack, the English army took up position on a ridge between the villages of Creçy and Wadicourt; the King taking as his post a windmill on the highest point of the ridge.

Edward, Prince of Wales, commanded the right division of the English army, assisted by the Earls of Oxford and Warwick and Sir John Chandos. The Prince’s division lay forward of the rest of the army and would take the brunt of the French attack. The left division had as its commander the Earl of Northampton.

Each division comprised spearmen in the rear, dismounted knights and men-at-arms in the centre. In a jagged line in the front of the army stood the army’s archers. Centred on the windmill stood the reserve, directly commanded by the King.

Edward the Black Prince at the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Walter Stanley Paget

At the back of the position the army’s baggage formed a park where the horses were held, surrounded by a wall of wagons with a single entrance.

Philip’s army came north from Abbeyville, the advance guard arriving before the Creçy-Wadicourt ridge at around midday on 26th August 1346. A party of French knights reconnoitred the English position and advised the King that his army should encamp and give battle the next day when concentrated and fresh. Philip agreed, but it was one thing to make such a decision and quite another to impose it upon the army’s top level of arrogant and independent minded nobles; all jealous of each other and determined to show themselves the champions of France. Most of the army’s leaders were for disposing of the English army without delay, forcing Philip to concede that the attack be made that afternoon.

It was the role of the Constable of France to command the kingdom’s feudal army in battle; but the English had taken the Constable, Raoul, Count of Eu, at Caen. His authority and experience was sorely missed at Creçy, as the King’s officers attempted to control the mass of the army and direct it into the attack.

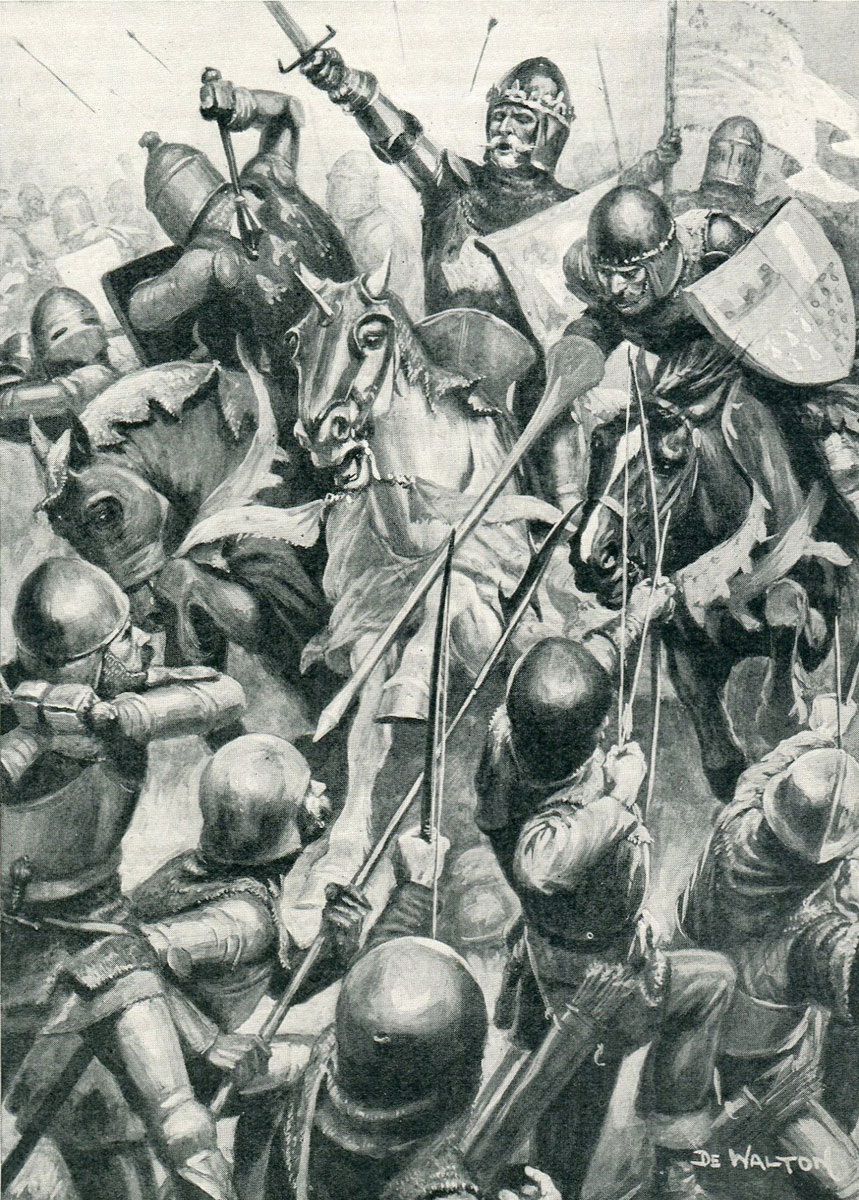

Charge of the French knights at the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Harry Payne

The Genoese formed the van, commanded by Antonio Doria and Carlo Grimaldi. The Duke D’Alençon led the following division of knights and men-at-arms; among them the blind King John of Bohemia, closely accompanied by two of his knights, their horses strapped on each side of the old monarch’s mount. In D’Alençon’s division rode two more monarchs; the King of the Romans and the displaced King of Majorca. The Duke of Lorraine and the Court of Blois commanded the next division, while King Philip led the rearguard.

The French knights attack at the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Richard Caton Woodville

At around 4pm the French moved forward for the assault, marching up the track that led to the English position. As they advanced, a sudden rainstorm swirled around the two armies. The English archers removed their bowstrings to cover inside their jackets and hats; the crossbowmen could take no such precautions with their cumbersome weapons.

As the French army advanced the chronicler Froissart describes the Genoese as whooping and shouting. Once the English formation was within crossbow range the Genoese discharged their bolts; but the rain had loosened the strings of their weapons and the shots fell short.

Froissart portrayed the response: “The English archers each stepped forth one pace, drew the bowstring to his ear, and let their arrows fly; so wholly and so thick that it seemed as snow.”

Blind King John of Bohemia at the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: print by DE Walton

The barrage inflicted significant casualties on the Genoese and forced them to retreat, exciting the contempt of the French knights coming up behind, who rode them down.

The clash of the retreating Genoese against the advancing cavalry threw the French army into confusion. The following divisions of knights and men-at-arms pressed into the melee at the bottom of the slope; but found themselves unable to move forward and subjected to a relentless storm of arrows, making many of the horses casualties.

The Black Prince finds the banner of King John of Bohemia after the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War and adopts his badge of the three white feathers, still the emblem of the Prince of Wales

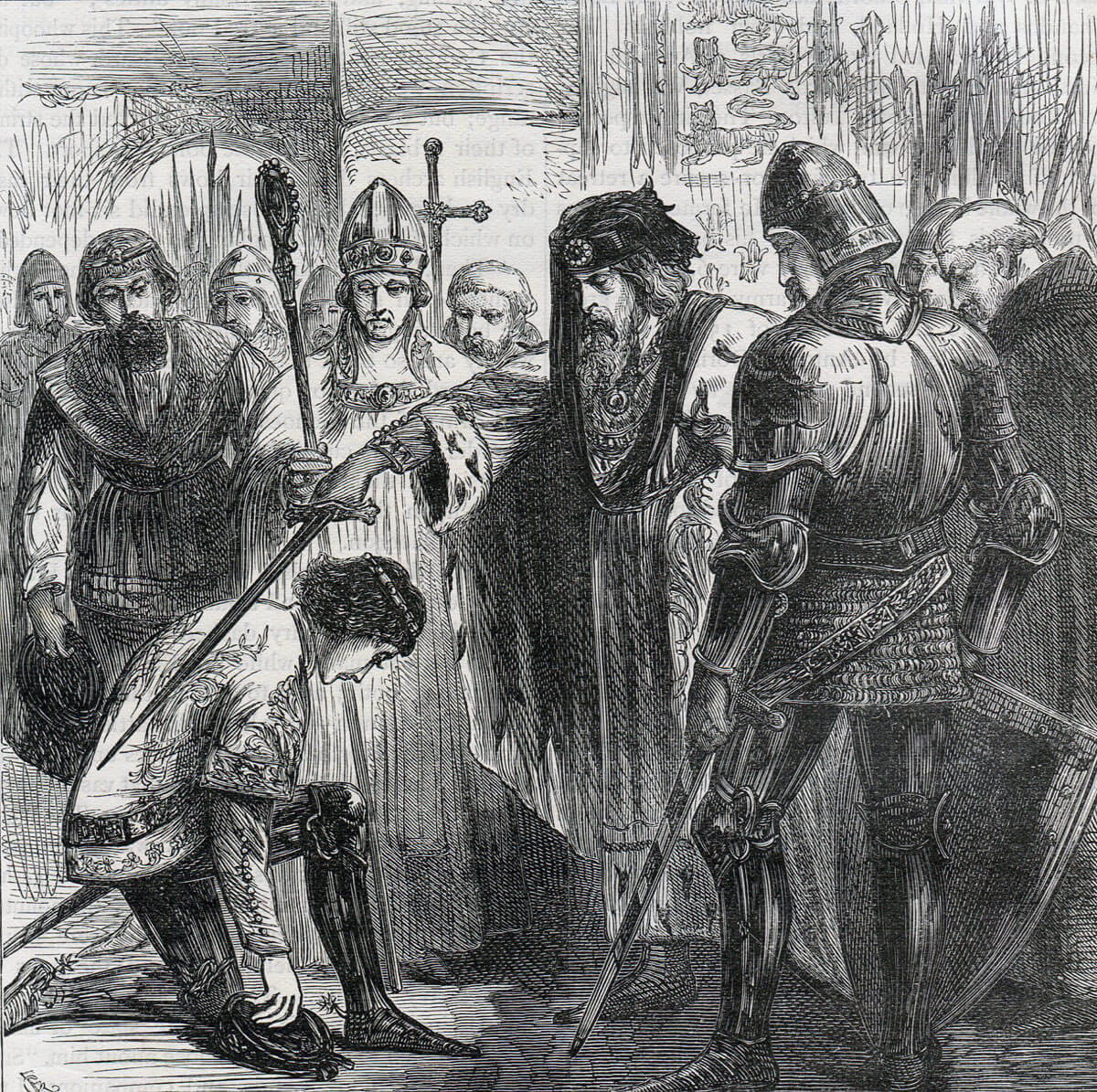

At this time a messenger arrived at King Edward’s post by the windmill seeking support for the Black Prince’s division. Seeing that the French could make little headway up the hill, Edward is reputed to have asked whether his son was dead or wounded and on being reassured said “I am confident he will repel the enemy without my help.” Turning to one of his courtiers the King commented “Let the boy win his spurs.”

The French chivalry made repeated attempts to charge up the slope, only to come to grief among the horses and men brought down by the barrage of arrows. King Edward’s five cannon trundled forward and added their fire from the flank of the English position.

In the course of the battle John, the blind King of Bohemia, riding at the Black Prince’s position, was struck down with his accompanying knights.

The struggle continued far into the night. At around midnight King Philip abandoned the carnage, riding away from the battlefield to the castle of La Boyes. Challenged as to his identity by the sentry on the wall above the closed gate the King called, bitterly, “Voici la fortune de la France” and was admitted.

The battle ended soon after the King’s departure, the surviving French knights and men-at-arms fleeing the battlefield. The English army remained in its position for the rest of the night.

In the morning the Welsh and Irish spearmen moved across the battlefield murdering and pillaging the wounded, sparing only those that seemed worth a ransom.

King Edward III greeting the Black Prince after the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Benjamin West

Casualties at the Battle of Creçy: English casualties were trifling, suggesting that few of the French knights reached the English line. French casualties are said to have been 30,000, including the Kings of Bohemia and Majorca, the Duke of Lorraine, the Count of Flanders, the Count of Blois, eight other counts and three archbishops.

Follow-up to the Battle of Creçy: Following the battle King Edward III marched his army north to Calais and besieged the town. It took the English a year to take Calais due to its resolute defence.

The disaster at Creçy left the French king unable to come to the aid of this important French port.

King Edward III knighting the Black Prince after the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Creçy:

- The Battle of Creçy established the six foot English yew bow as the dominant battlefield weapon of the time.

- The French army followed the Oriflamme, a sacred banner lodged in times of peace in the church of St Denis to the West of Paris, but brought out in times of war to lead the French into battle.

- After the battle, the Black Prince, according to tradition, adopted the emblem of the King of Bohemia, the three white feathers, and his motto “Ich Dien” (I serve); still the emblem of the Prince of Wales.

- Stone cannon balls were found on the battlefield in 1850 confirming the use by the English of the 5 pieces of artillery in the battle.

- The French went into battle with the cry “God and St Denis”. The English battle cry was “God and St George.”

- The English took 80 French standards in the battle. On the following day the display of standards was taken by the French country folk as indicating that the French army had prevailed. They gathered at Creçy only to be pillaged and murdered by Edward’s foot soldiers.

- Raoul, Count of Eu, the Constable of France, spent several years in captivity in England. During that time he took an enthusiastic part in the festivities at court, particularly the jousting. Word got back to the French king. On his return Raoul was tried for treason and beheaded.

King Edward III greets the Black Prince after the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War

References for the Battle of Creçy:

The Hundred Years War by Alfred H. Burne

Trial by Battle, Volume I of the four volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

The Hundred Years War by Robin Neillands.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Caen

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Calais

The Black Prince viewing the body of King John of Bohemia after the Battle of Creçy on 26th August 1346 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Julian Story