The English victory over the French king’s army on 25th October 1415 in the Hundred Years War immortalized in Williams Shakespeare’s play “Henry V”

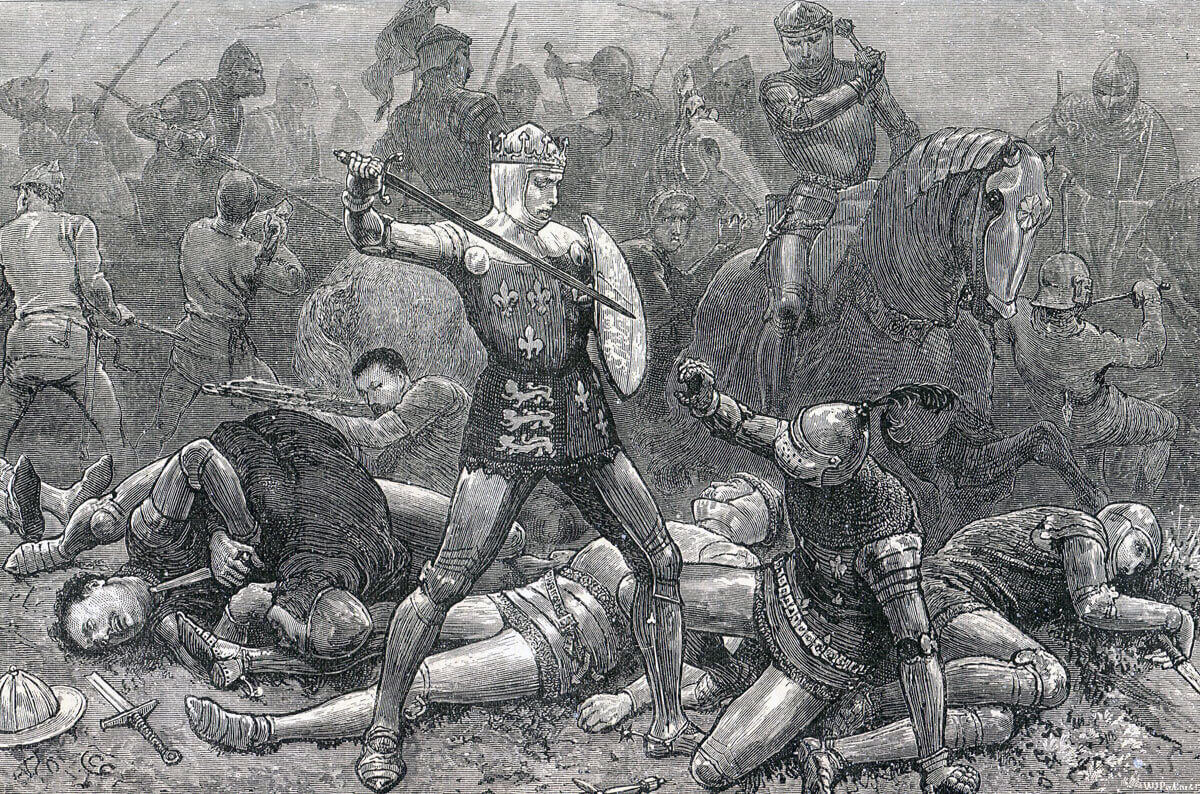

King Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt on 25th October 1415 in the Hundred Years War: picture by Harry Payne

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Harfleur

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Baugé

War: Hundred Years War.

Date of the Battle of Agincourt: 25th October 1415.

Place of the Battle of Agincourt: Northern France

Combatants at the Battle of Agincourt: An English and Welsh army against a French army.

Commanders at the Battle of Agincourt: King Henry V of England against the Constable of France, Charles d’Albret, Comte de Dreux.

Size of the armies at the Battle of Agincourt: The English army landed in France and besieged the port town of Harfleur some 30,000 strong. The siege took its toll, many in the army dying of disease, and a strong garrison had to be left to defend the captured port. At the Battle of Agincourt Henry’s army was probably around 5,000 knights, men-at-arms and archers. Estimates of the size of the French army vary widely, from 30,000 to as high as 100,000.

Uniforms, arms and equipment at the Battle of Agincourt: Knights wore steel plate armour of greater thickness and sophistication than at Creçy with visored helmets. Two-handed swords were coming into vogue as the battle weapon of the gentry. Otherwise weapons remained the lance, shield, sword, various forms of mace or club and dagger. Each knight wore his coat of arms on his surcoat and shield.

King Henry V prays with his army before the Battle of Agincourt on 25th October 1415 in the Hundred Years War

The English and Welsh archers carried a more powerful bow than their fathers and grandfathers under Edward III and the Black Prince. Armour piercing arrow heads made this weapon more deadly than its predecessor, stocks of thousands of arrows being built up in the Tower of London in preparation for war.

For hand-to-hand combat the archers carried swords, daggers, hatchets and war hammers. They wore jackets and loose hose; although many were rendered bare foot by the time of the battle from the long harrowing march from Harfleur. Archers’ headgear was a skull cap either of boiled leather or wickerwork ribbed with a steel frame.

It is claimed that many of the archers stripped off their upper garments for the battle to ease the use of their bows.

King Henry wore a polished and plumed bascinet helmet for the battle, surmounted by a gold crown. His surcoat was emblazoned with the arms of England and France.

Winner of the Battle of Agincourt: King Henry V of England won a decisive victory in the battle.

Account of the Battle of Agincourt: On his accession to the throne of England in April 1413 Henry V resolved to revive the war against France and press his claim to the French throne. Fitful negotiations between the two countries resumed, in which Henry made unacceptable demands that the French emissaries rejected with increasing alarm. All the while England prepared for war.

Shakespeare imaginatively incorporated into his portrayal of these negotiations a gift from the French Dauphin of a barrel of tennis balls that Henry threatened to turn into cannon shot.

Over the winter of 1414 to 1415 the King ordered his officers to commandeer shipping to transport his army, assembling at Southampton, across the Channel.

In August 1415 Henry’s army landed at Harfleur and began the siege of the town.

Harfleur finally surrendered on 22nd September 1415, no French army having appeared to relieve it.

Henry now faced a dilemma. The late departure of the army from England and the unexpectedly stubborn resistance of the Harfleur garrison left little of the campaigning season. Large forces were assembling round him; the French barons putting aside their fractious quarrelling to confront this foreign invasion; even Duke John of Burgundy sending a detachment to the main French army.

Henry assembled his council and informed it that he intended to march from Harfleur to Calais, ignoring his councillors’ misgivings at this foolhardy and apparently pointless scheme: Henry could go to Calais by sea with impunity. He had no need to risk his army by marching across the front of powerful French forces and hazarding the crossings of the Seine and the Somme Rivers (with all the difficulties Edward III had encountered before Creçy).

King Henry V of England, the

victor of Battle of Agincourt on 25th October 1415 in the Hundred Years War

Henry sent a messenger by sea to Calais ordering the Governor of the town, Sir William Bardolph, to march to the crossing point in the estuary of the Somme that Edward III had used in 1346 and hold it open for Henry’s army.

On 8th October 1415 the English army marched out of Harfleur on its 100 mile journey to Calais.

At the Somme estuary there was no sign of Bardolph and in his place a French force barred the crossing. The French were gathering all around Henry, contingents guarding the bridges and fords along the Somme for a considerable distance.

Henry marched south east up the left bank of the river, a French force keeping pace and opposing any attempt to cross. Finally the English army was able to outstrip the shadowing Frenchmen by cutting straight across a bow in the river, crossing and resuming the march north east towards Calais. In the face of the gathering French armies Henry ordered his archers to cut sharpened staves to form a barrier against mounted attack.

On 24th October 1415 the English army, led by a screen of scouts, marched through the Picardy town of Frévent, now within 30 miles of Calais and safety.

As the army entered the valley beyond the town, the scouts came riding back at speed with the news that an immense army blocked the road. The French had managed to march past the English and cut across their route during the delay on the Somme.

Medieval illustration of the Battle of Agincourt, the opposing Royal Standards displayed; England on the right; France on the left. The English Royal Standard incorporates the Lilies of France showing the claim of the Kings of England to the French throne

A Welsh man-at-arms, David Gambe, on being questioned by King Henry as to the size of the French army, said “There are enough to kill, enough to capture and enough to run away.”

Beyond the village of Maisoncelles the French came into sight, a mass of knights and men-at-arms spilling across the valley from the East. Seeing that he could not pass without giving battle Henry ordered his army to encamp and prepare to fight the next day.

That evening an air of resignation hung over the English, caused by the heavy rain that began to fall and the enormous French camp two miles up the road, marked in the dark by myriads of twinkling fires, laughter and music: the French had little doubt but that they would prevail the next day.

During the night Henry made his way around his army giving words of encouragement; again a dramatic episode made much of by Shakespeare.

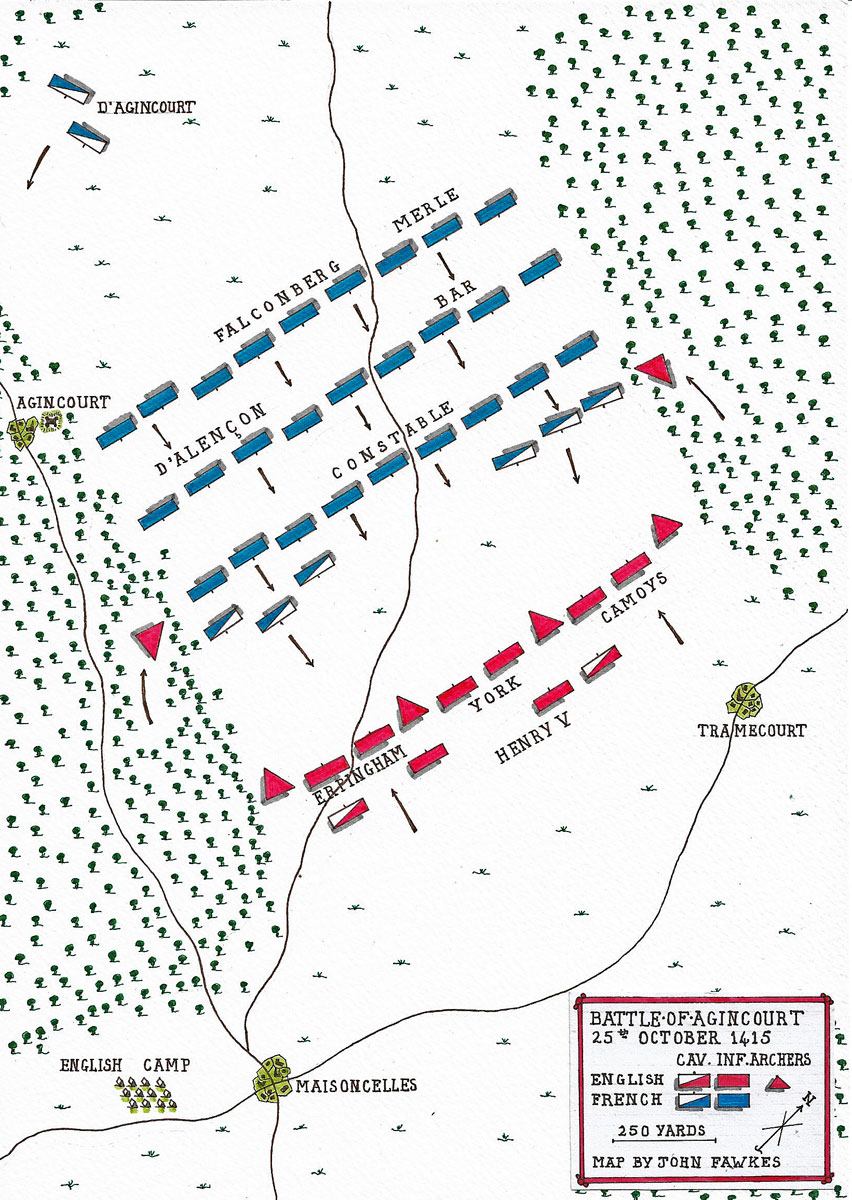

The next morning, 25th October 1415, the feast of St Crispin and public holiday in England, the English army marched out of Maisoncelles, taking up position across the road to Calais in three divisions of knights and men-at-arms; commanded by Lord Camoys on the right, the Duke of York in the centre and Sir Thomas Erpingham on the left. The Archers formed wedged divisions along the front.

Further down the road the French army formed for battle.

The Constable of France led the first French line. The Dukes of Bar and d’Alençon led the second and the Counts of Merle and Falconberg led the third.

In front of the English position forests approached the road from each side, leaving an area of muddy plough between them, insufficient for the French army to deploy with ease when every French knight of significance wished to be in the front with his retinue; the mass of knights and men-at-arms too compacted and unwieldy to manoeuvre or control.

The English soldiers knelt down before the battle commenced and kissed the ground as a symbol that they might be returning to the earth before the day was over.

Henry’s men waited for the French to begin the attack but there was no movement in the opposing army. It may be that there was inadequate overall command and no central decision made when to commence the assault or that the French were waiting for further contingents to arrive and take their station.

Finally Henry, urged to begin the battle by his commanders, gave the command “Forward banners” and the army advanced with trumpets blaring. Once in arrow range of the French Henry gave the command to halt and the divisions closed up, the archers setting their pointed staves in the ground forming a fence leaning outwards towards the French. Now within the confines of the two woods Henry directed parties of archers and men-at-arms to move through the trees nearer to the French.

On the king’s signal the English archers opened a devastating fire on the compact mass of French knights and men-at-arms.

After the initial shock the front line of the French army moved forward to the charge. In the narrow confines of the muddy rain soaked ploughland the charge quickly reduced to a stumbling walk, impeded by the floundering men and horses shot down by the archers, the arrow storm from the front compounded by the fire of the English concealed in the woods on the flanks.

The battle raged over the stake fence along the English line, the archers abandoning their bows and joining the knights and men-at-arms in hand to hand combat with the French cavalry, much of it now dismounted; the soldiers from the woods attacking on the flanks.

Within two hours of the battle beginning it was clear that the English had won. While individual French soldiers fought hard, it was from desperation as the English knights, men-at-arms and archers overwhelmed the struggling mass, taking as prisoner those who might be worth a ransom and killing the rest.

King Henry V and the Duke D’Alençon at the Battle of Agincourt on 25th October 1415 in the Hundred Years War

The Duke D’Alençon bringing up his division to assist the first line was overcome and about to surrender to Henry himself when he was struck dead. The Constable of France, Charles D’Albret, was killed with numbers of other prominent French nobles, the Dukes d’Orleans and de Brabant among them.

The French third line hovered on the edge of the field uncertain whether to take the risk of joining the fight until Henry sent a herald to order them off the battlefield on pain of receiving no quarter. The third line melted away.

King Henry V defends his brother the Duke of Gloucester at the Battle of Agincourt on 25th October 1415 in the Hundred Years War

On the English side the Duke of York died, trampled into the mud, while Henry himself defended his wounded brother, the Duke of Gloucester, against a mob of Frenchmen.

The main battle was finished by midday, the remnants of the French army streaming away from the battlefield while the English rounded up their prisoners.

At this point a small French force led by local nobles, Isambart d’Agincourt and Robert de Bournonville, used their local knowledge to march around the forests and fall on the English baggage at Maisoncelles. Fearing a renewal of the battle with an attack on his rear Henry ordered the French prisoners put to the sword, enforcing this order with the threat of hanging, and reformed his army to face the threat. The French raiders were quickly repelled but not before many of the prisoners were killed, an incident that marred the English victory by depriving the soldiers of the considerable sums they could have raised through ransom.

The final act of the battle was to disperse the remnants of the third line and ransack the French camp; before resuming the march to Calais, previously so difficult, now triumphantly easy.

Casualties at the Battle of Agincourt: It is believed that some 8,000 Frenchmen died in the battle, including many of the most senior nobles of France. English losses are thought to have been in the hundreds. The Duke of York died in the battle as did the Earl of Suffolk, whose father had died in the siege of Harfleur the month before.

Follow-up to the Battle of Agincourt: King Henry continued his march to Calais and returned to England for the celebrations to mark the victory at Agincourt. His army stayed at Calais but it was too late in the season for further campaigning.

Harfleur became an English town for the time being.

The French King Charles descended into a bout of insanity on hearing the terrible news of the defeat and France’s losses at Agincourt.

Anecdotes and traditions from the Battle of Agincourt:

- King Henry knighted David Gambe as he lay dying in the mud after the battle.

- After the battle Henry V entertained his senior commanders to dinner, waited on by captured French knights.

- During the battle an English knight, Sir Piers Legge of Lyme Hall, lay wounded in the mud while his mastiff dog fought off the French men-at-arms. Only when Sir Piers’ squire and servants came up after the battle would the mastiff allow anyone to approach his master. Sir Piers did not survive his wounds, but the dog returned to Lyme Hall and is reputed to have sired the English Mastiff breed.

- It was believed among the English archers during the Hundred Years War that the French intended to cut off the first and second right hand fingers of every captured archer to prevent him from again using a bow. The archers raised those two fingers to the advancing French as a gesture of defiance.

- Lord Camoys, a leading Catholic peer and the descendant of the commander of Henry V’s right flanking division, has his seat at Stonor in the South Oxfordshire Chilterns.

References for the Battle of Agincourt:

The Hundred Years War by Alfred H. Burne

Cursed Kings, Volume lV of the four volume record of the Hundred Years War by Jonathan Sumption.

The Art of War in the Middle Ages Volume Two by Sir Charles Oman.

The Hundred Years War by Robin Neillands.

British Battles by Grant.

The previous battle of the Hundred Years War is the Siege of Harfleur

The next battle of the Hundred Years War is the Battle of Baugé